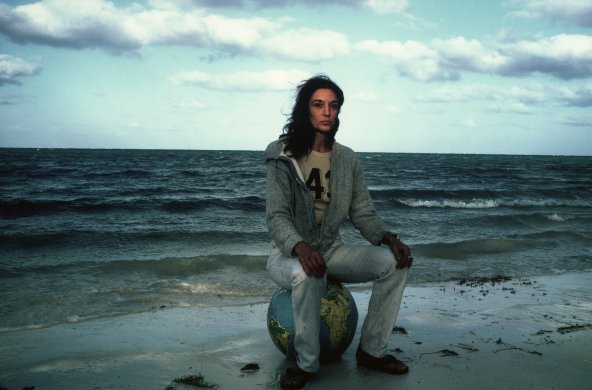

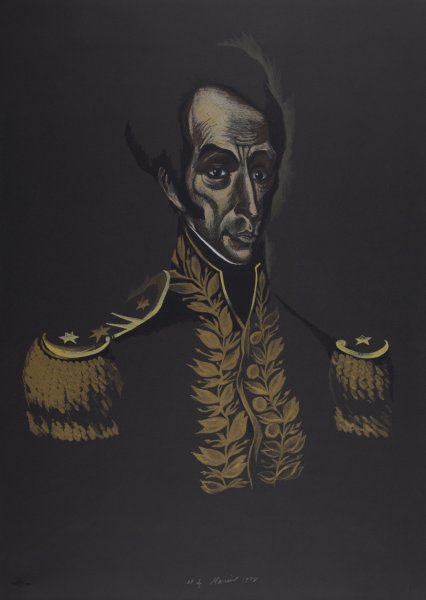

One of the most prominent artists of her generation, whose innovative work helped define the 1960s, Marisol (Venezuelan and American, 1930–2016) was born María Sol Escobar in Paris to a Venezuelan family. The family moved back to Venezuela around 1935, and Marisol spent her early years traveling between New York and Caracas. She drew continually from a very young age, and she adopted the name Marisol—which alludes to the Spanish words for “sea” and “sun”—in her early teens. She would use Marisol as her professional name for the rest of her life. In 1946, her family moved to Los Angeles, where she studied art at the Otis Art Institute and with Howard Warshaw at the Jepson Art Institute. She then briefly attended the Académie Julian and the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris before moving around 1950 to New York, where she took classes at the Art Students League (between 1951 and 1963); studied with Hans Hofmann (at his studios in New York and also in Provincetown, Massachusetts, between 1952 and 1955); and attended the New School for Social Research (in 1952) and the Brooklyn Museum Art School (between 1955 and 1957).

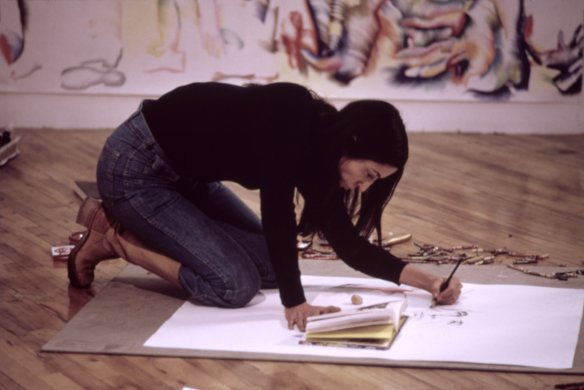

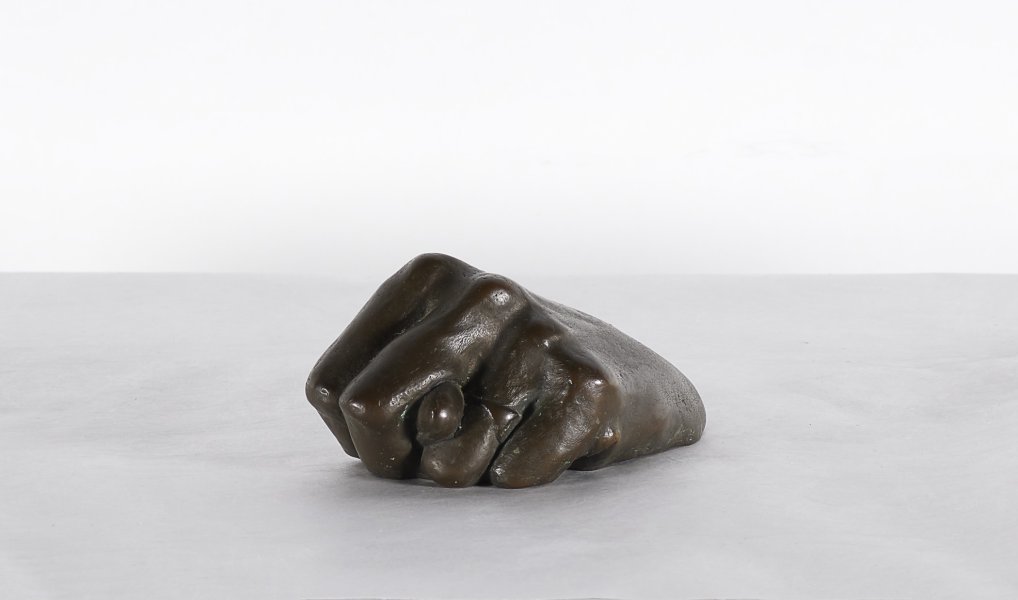

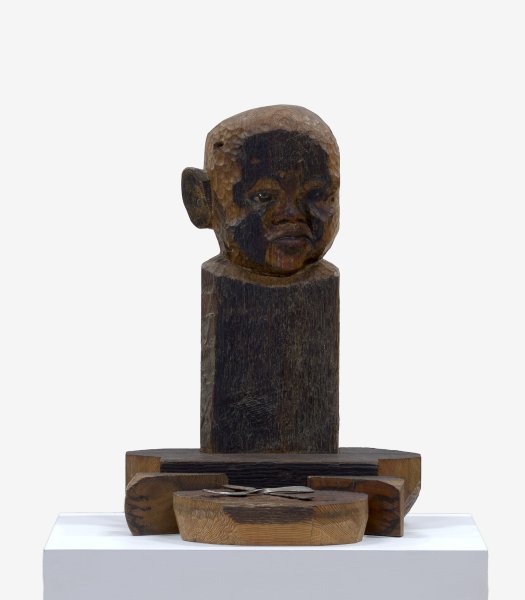

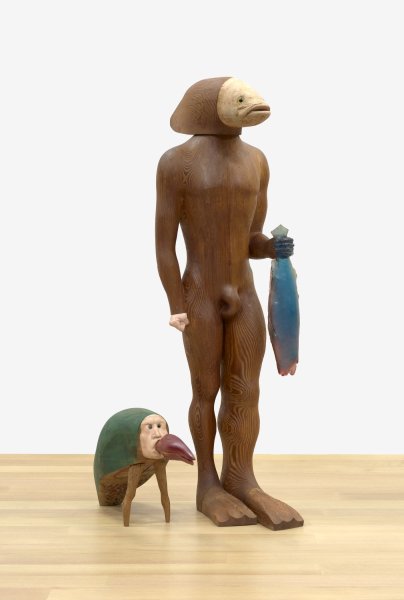

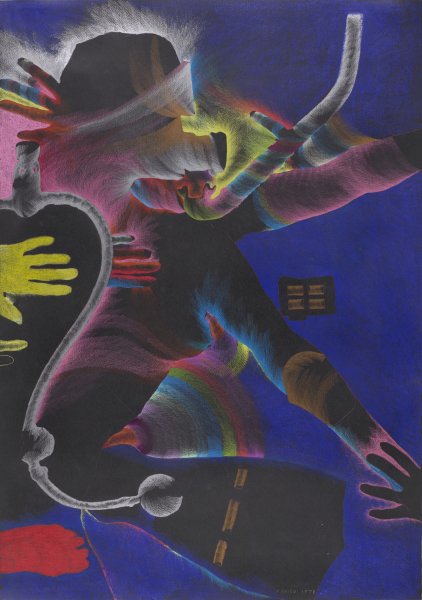

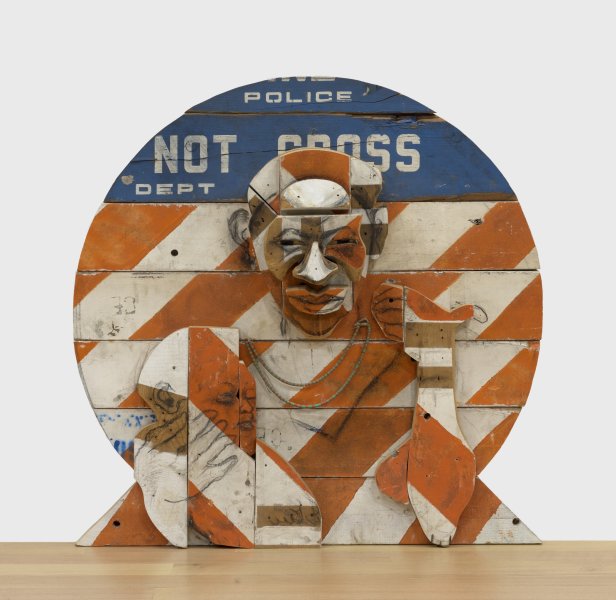

Like many of the artists who emerged in the early 1950s, Marisol was at first strongly influenced by the prevailing school of Abstract Expressionist painting. She came to know many of the figures associated with this group and was friends with artists such as Willem de Kooning. After seeing pre-Columbian art in Mexico while visiting her father and in a New York gallery show in the early 1950s, Marisol began making sculpture in 1954. At first she worked on a relatively small scale in terra-cotta and in wood, and used the lost-wax method of casting in bronze. Within a few years, however, she began focusing on life-size, totemic figures. These mixed-media assemblages combined wood with painting and found objects in a style that was sometimes quizzical or satirical but always highly accessible. When the Pop art movement emerged, Marisol’s works were often associated with it, although her sculptures were also distinct from the observations on mass media and mass culture put forward by friends and peers such as Andy Warhol. Marisol later stated, “I started doing something funny so I would be happier—and it worked.”

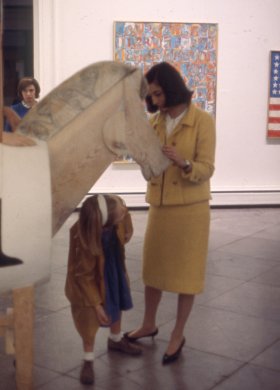

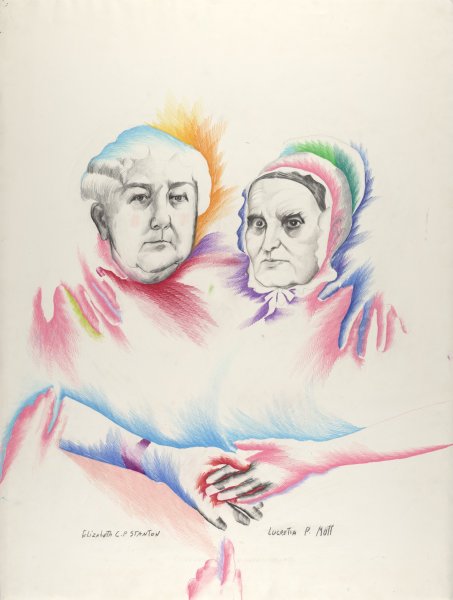

Marisol’s work quickly drew the attention of the legendary art dealer Leo Castelli, who in 1957 included her in a show along with Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg and gave her a solo exhibition at his gallery. Wider public acclaim came in 1962, following her first solo exhibition at Eleanor Ward’s Stable Gallery. The Albright-Knox Art Gallery was the first museum to formally acquire a sculpture of Marisol’s with a purchase from that show, and LIFE magazine featured her in its “Red-Hot Hundred” list. Images of Marisol’s work, reproduced in LIFE and elsewhere in the popular press, extended her reputation far beyond the art world. Her 1964 exhibition at the Stable Gallery received up to two thousand visitors a day, and her first solo show at the Sidney Janis Gallery in 1966 was even more popular. During the exhibition’s run, there was a regular queue of people waiting to see the remarkable life-size figures, many of which addressed the role of women in society and included plaster casts of Marisol’s own face and hands.

![[Working proof for Stage V of an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_099_V_o2.jpg?itok=80TUobwy)

![[Working proof for an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_099_R_o2.jpg?itok=Y1yU4KOh)

![[Working proof for Stage I of an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_098_o2.jpg?itok=zSRZr50Z)

![[Working proof for Stage III of an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_097_o2.jpg?itok=g1uTQ5D3)

![[Working proof for Stage V of an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_096_o2.jpg?itok=13LDyfxC)

![[Working proof for Stage IV of an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_095_o2.jpg?itok=UYBdj3fL)

![[Working proof for Stage VI of an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_094_o2.jpg?itok=Ky4B84W8)

![[Working proof for Stage V of "Gold Heart"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_091_o2.jpg?itok=j2oEgJYO)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_009_o2.jpg?itok=3qW3sLgW)

![[Stage II of an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_081_o2.jpg?itok=KLlkgR5F)

![[Working proof for Stage IV of an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_080_o2.jpg?itok=pB-uCZjI)

![[Working proof for Stage IV of an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_079_o2.jpg?itok=H1as1fV8)

![[Working proof for "Hate" (also known as "Lizard Kiss")]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_078_o2.jpg?itok=af4vCpWF)

![[Working proof for an Untitled lithograph]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_077_o2.jpg?itok=YHp0IvyU)

![[Working proof for an Untitled lithograph]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_076_o2.jpg?itok=BvbcLhvk)

![[Working proof for an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_075_o2.jpg?itok=snab46rN)

![[Working proof for Stage II of an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_074_o2.jpg?itok=7fpApj7r)

![[Test print for "Sun"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_073_o2.jpg?itok=gY0cSiZ_)

![[Test print for "Sun"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_072_o2.jpg?itok=NxqOZMw8)

![[Test print for "Love" (also known as "Erotic")]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_071_o2.jpg?itok=vF-7oWhm)

![[Test print for "Twins I"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_070_o2.jpg?itok=X2WuIdpe)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_007_o2.jpg?itok=VZTiFpTd)

![[Working proof for Stage I of "Gold Heart"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_068_o2.jpg?itok=rQvLYa4a)

![[Stage I of "Gold Heart"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_067_o2.jpg?itok=T7NP95BK)

![[Working proof for Stage IV of "Gold Heart"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_066_o2.jpg?itok=_PBoYLrp)

![[Working proof for Stage III of "Gold Heart"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_065_o2.jpg?itok=gFzEgj0R)

![[Stage III of "Gold Heart"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_064_o2.jpg?itok=pEq1xeMT)

![[Stage IV of "Gold Heart"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_063_o2.jpg?itok=gOgT9Zwy)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_062_o2.jpg?itok=g70axfGN)

![[Stage III of an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_061_o2.jpg?itok=EkgAxNtc)

![[Working proof for Stage VI of "Untitled"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_060_o2.jpg?itok=TLq_uFCF)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_006_o2.jpg?itok=LdQCjBmA)

![[Working proof for Stage V of "Untitled"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_059_o2.jpg?itok=Jl-U7aC0)

![[Working proof for Stage III of "Untitled"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_058_o2.jpg?itok=nYQkpJgs)

![[Working proof for Stage I of "Untitled"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_057_o2.jpg?itok=m5m5LRPM)

![[Test print for "Sat"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_056_o2.jpg?itok=Q5umq_wC)

![[Working proof for Stage II of an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_055_o2.jpg?itok=nsWdFec-)

![[Test print for "Budding"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_054_o2.jpg?itok=OTCMZJaz)

![[Test print for "Budding"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_053_o2.jpg?itok=J81dhRXy)

![[Test print for "Hate" (also known as "Lizard Kiss")]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_050_o2.jpg?itok=ahZFFhTr)

![[Test print for "Twins II"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_048_o2.jpg?itok=NhAdSb9M)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_046_o2.jpg?itok=e1FxHG4N)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_044_o2.jpg?itok=02fBv-RJ)

![[Test print for "Cultural Head"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_043_o2.jpg?itok=1hjlVJER)

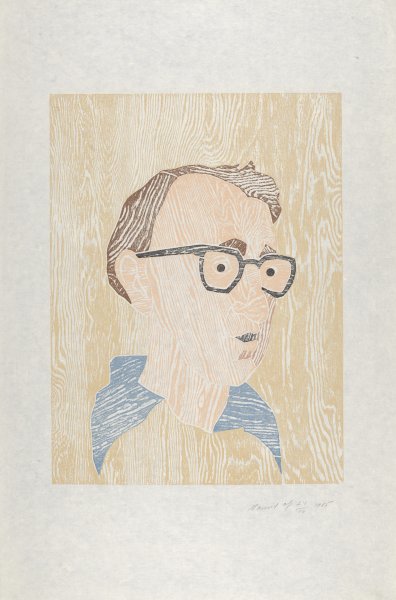

![[Test print for "Woody Allen"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_041_o2.jpg?itok=COkr1J8i)

![[Test print for "Woody Allen"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_040_o2.jpg?itok=P74CoRIJ)

![[Test print for "Love" (also known as "Erotic")]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_038_o2.jpg?itok=nYsrF-G0)

![[Test print for "Women's Equality from the Kent Bicentennial Portfolio: Spirit of Independence"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_037_o2.jpg?itok=3E8FDBy4)

![[Test print for "Love" (also known as "Erotic")]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_039_o2.jpg?itok=C_qPVWi6)

![[Cover design for "Marisol Prints" exhibition catalogue (1973), The New York Cultural Center]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_028_o2.jpg?itok=VgU_ZmLs)

![[Stage II of "Gold Heart"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_026_o2.jpg?itok=4l3SVlP6)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_027_o2.jpg?itok=9a5hmosy)

![[Working proof for Stage III of an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_025_o2.jpg?itok=G9WTRRTC)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_024_o2.jpg?itok=iVElbVw1)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_023_o2.jpg?itok=0x-zmc1Y)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_022_o2.jpg?itok=4Em8BtsO)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_021_o2.jpg?itok=elObdQGs)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_020_o2.jpg?itok=Fa3Um-ZZ)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_018_o2.jpg?itok=H7dMvJlL)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_019_o2.jpg?itok=FGsJbB9V)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_017_o2.jpg?itok=pvAUvKT0)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_016_o2.jpg?itok=k6LvR_Jf)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_013_o2.jpg?itok=sKvpcTMH)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_014_o2.jpg?itok=90sJcoqy)

![[Working proof for Stage V of "Untitled"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_112_o2.jpg?itok=G0ByzAoK)

![[Working proof for Stage V of "Untitled"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_111_o2.jpg?itok=xf4U042K)

![[Working proof for Stage VI of "Untitled"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_110_o2.jpg?itok=Rx-zyu4d)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_011_o2.jpg?itok=H7HlffPg)

![[Working proof for Stage I of "Untitled"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_108_o2.jpg?itok=hVONnt5U)

![[Working proof for Stage VI of "Untitled"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_109_o2.jpg?itok=E4TA_liO)

![[Working proof for Stage V of "Gold Heart"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_107_o2.jpg?itok=aRzkvyVN)

![[Stage V of an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_106_o2.jpg?itok=OwWVbXKu)

![[Stage IV of an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_105_o2.jpg?itok=Wx_Wpzei)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_104_o2.jpg?itok=I0dy6G8h)

![[Working proof for "Twins I"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_103_o2.jpg?itok=FUOEF7cW)

![[Working proof for Stage I of "Gold Heart"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_102_o2.jpg?itok=1OPdKeu8)

![[Working proof for an Untitled lithograph]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_101_o2.jpg?itok=0puY9H0D)

![[Working proof for an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_100_o2.jpg?itok=NQ94Ud7-)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_010_o2.jpg?itok=L3tLLWeu)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_055_o2.jpg?itok=xaYbL4sV)

![[Prepatory drawing for "Simón Bolívar"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_045_o2.jpg?itok=1i7lDmA6)

![[Preparatory drawing for "American Merchant Mariners' Memorial", 1991, The Battery, Manhattan, NY]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_046_o2.jpg?itok=ngu4m7m9)

![[Untitled Landscape]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_032_o2.jpg?itok=UamRall5)

![[Untitled Landscape]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_031_o2.jpg?itok=AF7uHPTs)

![[Untitled Landscape]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_030_o2.jpg?itok=DR0KEG1W)

![[Untitled Landscape]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_029_o2.jpg?itok=sYkFoYJ9)

![[Untitled Landscape]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_028_o2.jpg?itok=ygCkUsIS)

![[Set design study for "The Scarlet Letter", Martha Graham Dance Company, 1975]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_027_o2.jpg?itok=2Gz468jk)

![[Set design study for "The Scarlet Letter", Martha Graham Dance Company, 1975]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_026_o2.jpg?itok=SeAm9KOB)

![[Set design study for "The Scarlet Letter", Martha Graham Dance Company, 1975]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_025_o2.jpg?itok=uLYOMudo)

![[Set design study for "The Scarlet Letter", Martha Graham Dance Company, 1975]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_024_o2.jpg?itok=NIsEyEWC)

![[Set design study for "The Scarlet Letter", Martha Graham Dance Company, 1975]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_023_o2.jpg?itok=glk1gaD4)

![[Set design study for "The Scarlet Letter", Martha Graham Dance Company, 1975]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_022_o2.jpg?itok=sFf6N5_f)

![[Costume design sketch for "Ecuatorial", Martha Graham Dance Company, 1978]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_021_o2.jpg?itok=luf_Lhg4)

![[Costume design sketch for "Ecuatorial", Martha Graham Dance Company, 1978]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_020_o2.jpg?itok=0eVCwFY4)

![[Costume design sketch for "Ecuatorial", Martha Graham Dance Company, 1978]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_019_o2.jpg?itok=oi8e-bLZ)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_018_o2.jpg?itok=DM07HUAf)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_017_o2.jpg?itok=ZtYReZVp)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_016_o2.jpg?itok=82X08255)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_015_o2.jpg?itok=GmdVbcYz)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_012_o2.jpg?itok=Tc0jyTtw)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2024_010_o2.jpg?itok=6MA3DqLK)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_012_o2.jpg?itok=gNtRTl5X)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_005_o2.jpg?itok=Dy2QEwzY)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_008_o2.jpg?itok=o0gQZX_U)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_015_o2.jpg?itok=LUR77PwQ)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2022_007_a-f_o2.jpg?itok=t9B6Ejzh)

![[Study for monument to Emily, John, and Washington Roebling, unrealized, Brooklyn, NY]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_071_a-c_o2.jpg?itok=_Nv0GvX_)

![[Study for monument to Juan Pedro López, 2000, Plaza Juan Pedro López, Caracas, Venezuela]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2022_012_a-b_o2.jpg?itok=PZaD-6dv)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2022_025_o2.jpg?itok=EDkkI3nB)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_067_o2.jpg?itok=G4tMk_Te)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_236_o2.jpg?itok=mYK7shCB)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_117_o2.jpg?itok=tmbifzP9)

![[Caracas N.Y.]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_229_o2.jpg?itok=a-tFrNQ2)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_120_o2.jpg?itok=IDrV9Mrs)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_126_o2.jpg?itok=DPWSs-JF)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_113_o2.jpg?itok=s78LyMNs)

![[Prepatory drawing for "Woody Allen"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_234_o2.jpg?itok=dVB8Q8Be)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_118_o2.jpg?itok=kP--_XYY)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_237_o2.jpg?itok=3BxO6SSP)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_115_o2.jpg?itok=BvzCmiZm)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_239_o2.jpg?itok=CMzCNrA9)

![[Happy Birthday (Sidney)]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_231_o2.jpg?itok=_TmbHrZc)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_242_o2.jpg?itok=V96BNfkt)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_122_o2.jpg?itok=BD2qRiYx)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_245_o2.jpg?itok=Q5EDXEM7)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_119_o2.jpg?itok=Lr8fDXSp)

![[Caracas]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_230_o2.jpg?itok=9T7CZIZ7)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_110_o2.jpg?itok=jPEMLTJb)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_244_o2.jpg?itok=DhFLcR7B)

![[Preparatory drawing for "Pappagallo" and an Untitled, unfinished work]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_235_o2.jpg?itok=SAxTsoOj)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_243_o2.jpg?itok=Hxe7r4mQ)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_116_o2.jpg?itok=1uVt_es-)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_114_o2.jpg?itok=jnNJWX3h)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_241_o2.jpg?itok=L6cuO27M)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_127_o2.jpg?itok=5bF7tY11)

![[Prepatory drawing for "Woody Allen"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_233_o2.jpg?itok=dPrHNH--)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_125_o2.jpg?itok=GrDF5ajS)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_123_o2.jpg?itok=TEAVPTsw)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_124_o2.jpg?itok=RZUQntaG)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_111_o2.jpg?itok=D7_0AR9Z)

![[Preparatory drawing for "Meeting of the Universe"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_232_o2.jpg?itok=IxPEAap1)

![[Untitled Landscape]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_246_o2.jpg?itok=yDcGaOPH)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_240_o2.jpg?itok=FDZNK-UF)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_130_o2.jpg?itok=QFOMFmAd)

![[Test print for "Love" (also known as "Erotic")]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_103_o2.jpg?itok=ah0r4mCf)

![[Working proof for "Hate" (also known as "Lizard Kiss")]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_128_o2.jpg?itok=LLdcWvJV)

![[Working proof for "Hand in Leaf"]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_105_o2.jpg?itok=M4gxlu_5)

![[Working proof for an Untitled lithograph suite]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2024_082_o2.jpg?itok=8JiHv8Fo)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_228_o2.jpg?itok=INBxtXPW)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_247_o2.jpg?itok=lmKaVWsx)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_238_o2.jpg?itok=C8MW7tnz)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_112_o2.jpg?itok=bSCNX7nP)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_121_o2.jpg?itok=iiYbwZBD)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_109_o2.jpg?itok=a6HYFQ64)

![[Study for Monument to Father Damien (1968), Hawaii State Capitol, Honolulu]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2022_019_o2.jpg?itok=sbzykhPW)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_171_o2.jpg?itok=wvFMvBbU)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_169_o2.jpg?itok=oeoSZ5o3)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_163_o2.jpg?itok=TzZNvyRb)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_166_V_o2.jpg?itok=o0uucLRl)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_166_R_o2.jpg?itok=4P2TCzvB)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_081_o2.jpg?itok=_hCKLZ7w)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_078_o2.jpg?itok=n1NxuEAI)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_128_005_o2.jpg?itok=kZI5KxyC)

![[Study for "The Fishman", 1973]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_063_o2.jpg?itok=u0Ek3CJ8)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_074_o2.jpg?itok=ztLSDTmc)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_073_o2.jpg?itok=n8Z1zrWL)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_070_o2.jpg?itok=UjIgE4h1)

![[Study for "The Fishman", 1973]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_062_o2.jpg?itok=h3OZ3xl2)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_058_o2.jpg?itok=HWnQyX_t)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_072_o2.jpg?itok=Ovm8O2cU)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_059_o2.jpg?itok=Lu6Pqeg6)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_075_o2.jpg?itok=NUwWMbAw)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_066_o2.jpg?itok=DuxOyqoQ)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_067_o2.jpg?itok=maeHIMA5)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_068_o2.jpg?itok=REutKJXm)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_065_o2.jpg?itok=OxejH0GT)

![[Untitled (The grass under Guatemala)]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_071_o2.jpg?itok=6sxYJpla)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_057_o2.jpg?itok=WPXSvwSW)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_076_o2.jpg?itok=YLooiJNE)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_077_o2.jpg?itok=O731Vkc1)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_078_o2.jpg?itok=5tDvr-WU)

![[Study for monument to Simón Bolívar, 1977, United Nations Headquarters, New York, NY]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_069_o2.jpg?itok=Gka-Zh_n)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_082_o2.jpg?itok=BkIGsOYK)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_095_o2.jpg?itok=Qnz8BhVb)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_093_o2.jpg?itok=hibtocIl)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_106_o2.jpg?itok=I3QUft6F)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_079_o2.jpg?itok=EGihuC7a)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_080_o2.jpg?itok=8WMnj53L)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_086_o2.jpg?itok=wXi5UNXP)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_089_o2.jpg?itok=7aLRQIWN)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_099_o2.jpg?itok=1oDXspO_)

![[Untitled (possible study for monument to Simón Bolívar, unrealized)]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_104_o2.jpg?itok=jDpWvH8p)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_098_o2.jpg?itok=SfhBXgEu)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_097_o2.jpg?itok=OLg1gLyv)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_087_o2.jpg?itok=N51LTFml)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_092_o2.jpg?itok=tFHc9aqk)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_091_o2.jpg?itok=5_7zkDi3)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_088_R_o2.jpg?itok=Pyy6Boxd)

![[Untitled (possible study for monument to Simón Bolívar, unrealized)]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_105_o2.jpg?itok=4m0hz8m6)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_090_o2.jpg?itok=VI-gqU65)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_088_V_o2.jpg?itok=B6zOjh1W)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_094_o2.jpg?itok=lftXp5Q9)

![[Untitled (Casita Maria)]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_101_o2.jpg?itok=pGHeRxx4)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_103_o2.jpg?itok=M-OkFCO7)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_102_o2.jpg?itok=WFJ3pARW)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_084_o2.jpg?itok=u-7ALcht)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_085_o2.jpg?itok=e_5zHStn)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_083_o2.jpg?itok=5KD8scwV)

![[Untitled (Casita Maria)]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_100_o2.jpg?itok=W_L_sYIM)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_081_o2.jpg?itok=VoZLFXYu)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_107_o2.jpg?itok=NyKwAucQ)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_060_o2.jpg?itok=7vZEm3Ms)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_116_o2.jpg?itok=zwvIAaj3)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_108_o2.jpg?itok=RYrTGx6c)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_059_o2.jpg?itok=5obsmhgK)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_115_o2.jpg?itok=GCdoRoaF)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_064_o2.jpg?itok=VxV3Evye)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_109_o2.jpg?itok=m5RMjv60)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_110_o2.jpg?itok=-nbtTjbn)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_062_o2.jpg?itok=rG285xoE)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_061_o2.jpg?itok=QjHv5SE2)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_133_o2.jpg?itok=L418j7g6)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_063_o2.jpg?itok=qYfNppRw)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_065_o2.jpg?itok=aGQw1e-U)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_113_o2.jpg?itok=4yBOInGJ)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_114_o2.jpg?itok=Cnfz98W5)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_111_o2.jpg?itok=kcdFerWe)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_126_o2.jpg?itok=lNk7zAWr)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_127_o2.jpg?itok=cryQ5GuG)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_128_o2.jpg?itok=jSv62Ppq)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_129_o2.jpg?itok=Bz5vinA6)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_131_o2.jpg?itok=9tM0eEu2)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_132_o2.jpg?itok=-mLyy0sC)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_112_o2.jpg?itok=8I-qB6qp)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_125_o2.jpg?itok=6AgPlzDU)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_058_o2.jpg?itok=LJKgeMsO)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_124_o2.jpg?itok=Dzd3Ya48)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_123_o2.jpg?itok=lDpKh7Rv)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_122_V_o2.jpg?itok=Y4F7-b_H)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_121_o2.jpg?itok=SRKcf5E2)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_120_o2.jpg?itok=9bG7UfWo)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_122_R_o2.jpg?itok=l3qmWJO8)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_118_o2.jpg?itok=4MZICSo1)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_134_o2.jpg?itok=YTIVT8_o)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_149_o2.jpg?itok=8_iTUmfx)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_148_o2.jpg?itok=5Zx8CFEW)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_147_o2.jpg?itok=o22UCw-H)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_152_o2.jpg?itok=i8hV1xtv)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_154_o2.jpg?itok=AEpm155q)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_135_o2.jpg?itok=f2opx-zT)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_142_o2.jpg?itok=4Y0DjiNs)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_145_o2.jpg?itok=vjk7f44E)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_139_o2.jpg?itok=s6Rs6RnL)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_137_o2.jpg?itok=oE-Bjvb7)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_138_o2.jpg?itok=9VRKKB5I)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_140_o2.jpg?itok=3IasLiNo)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_141_o2.jpg?itok=Gm1uSHCB)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_143_o2.jpg?itok=9UTT1hW0)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_136_o2.jpg?itok=XmY1-cZD)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_146_o2.jpg?itok=zNKwKQcL)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_153_o2.jpg?itok=tFsAkcv3)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_185_o2.jpg?itok=HwuX6Tdw)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_159_o2.jpg?itok=ea1i29b1)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_187_o2.jpg?itok=ie6HnwEh)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_194_o2.jpg?itok=vxrAu-cO)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_168_o2.jpg?itok=4pxX999m)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_186_o2.jpg?itok=LvHM437f)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_160_o2.jpg?itok=6nwBohlI)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_184_o2.jpg?itok=4iKGl0_X)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_193_o2.jpg?itok=QQCoz7GO)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_188_o2.jpg?itok=6SAOaefE)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_192_o2.jpg?itok=neLUagGV)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_191_o2.jpg?itok=qR3hut8r)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_190_o2.jpg?itok=oAc5Qm4Z)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_189_o2.jpg?itok=A5Cb6qz8)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_167_o2.jpg?itok=R1RhR-eE)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_156_o2.jpg?itok=SasUlVMq)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_183_o2.jpg?itok=UlMbFkWt)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_073_o2.jpg?itok=3n81oYnB)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_175_o2.jpg?itok=e-mDlylF)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_075_o2.jpg?itok=5OZy7bxE)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_180_o2.jpg?itok=oQ9OHgLi)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_076_o2.jpg?itok=pA4JIIX7)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_178_o2.jpg?itok=DIlKy19a)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_084_o2.jpg?itok=9eHUqWhc)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_083_o2.jpg?itok=UniWHTaH)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_082_o2.jpg?itok=1ouUdnal)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_181_o2.jpg?itok=eB_BYYa8)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_164_o2.jpg?itok=1KIuDgd2)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_173_o2.jpg?itok=w5Dmxtir)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_172_o2.jpg?itok=AWbtf3lF)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_170_o2.jpg?itok=C8GG68DT)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_179_o2.jpg?itok=F0VMArLp)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_165_o2.jpg?itok=LrH7t0Yr)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_195_o2.jpg?itok=04tShW0z)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_203_o2.jpg?itok=11cOQa97)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_202_o2.jpg?itok=0aROAjYk)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_201_o2.jpg?itok=zS3fPvgt)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_198_o2.jpg?itok=-LzXBQSM)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_200_o2.jpg?itok=JE104vA8)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_197_o2.jpg?itok=K39uVpaH)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_204_o2.jpg?itok=_jiNcKcy)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_161_o2.jpg?itok=zwY7F2l4)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_117_o2.jpg?itok=xemW8Lc7)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_119_o2.jpg?itok=1T-7oXR9)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_144_o2.jpg?itok=RJSF09Ri)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_150_o2.jpg?itok=ZItyKKBd)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_155_o2.jpg?itok=l5c88Ktt)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_196_o2.jpg?itok=aqQswEfs)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_199_o2.jpg?itok=CZYwwiRQ)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_060_o2.jpg?itok=whfQ31Bk)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_061_o2.jpg?itok=IkKTPisn)

![[Study for monument to Juan Pedro López, 2000, Plaza Juan Pedro López, Caracas, Venezuela]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_064_o2.jpg?itok=31ZvRLs5)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_077_o2.jpg?itok=mOJhaHMG)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2023_056_o2.jpg?itok=gG2rfqu_)

![[Costume design sketch for "Ecuatorial", Martha Graham Dance Company, 1978]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_030_o2.jpg?itok=pDEhwIV4)

![[Costume design sketch for "Ecuatorial", Martha Graham Dance Company, 1978]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_031_o2.jpg?itok=rwjOaTrY)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_028_o2.jpg?itok=rRwzIT_6)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_128_003_o2.jpg?itok=x-PB4QWq)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_128_004_o2.jpg?itok=7lNnn7j5)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_128_002_o2.jpg?itok=BJXsU53R)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_128_001_o2.jpg?itok=THZ5QFz3)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_128_006_o2.jpg?itok=_R15Jz3U)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_128_007_o2.jpg?itok=MTd8u9Fc)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_128_008_o2.jpg?itok=mh6iU5t8)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_128_009_o2.jpg?itok=U1Vx0OVT)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_128_010_o2.jpg?itok=r3PEQVF9)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_128_011_o2.jpg?itok=LOVmOb4D)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_025_004_o2.jpg?itok=4JwJB1Ns)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_068_o2.jpg?itok=m7ou8NA_)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_025_005_o2.jpg?itok=C1UGuon4)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_029_o2.jpg?itok=zP69iGpG)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2022_032_o2.jpg?itok=cWkfEf39)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_022_o2.jpg?itok=t2M_xXsP)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_018_o2.jpg?itok=CNO7m1Eq)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_019_o2.jpg?itok=AajW5UfU)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_020_o2.jpg?itok=uU0P_c3j)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_021_o2.jpg?itok=f087pWL2)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_024_o2.jpg?itok=2x5QABVL)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_023_o2.jpg?itok=2iFaUjHW)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_017_o2.jpg?itok=5kzg8_ZE)

![[Untitled (The only salvation for an American is to become queer)]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_004_o2.jpg?itok=zfvVGjwP)

![[Sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_128_001-011_o2.jpg?itok=3ZE12bGM)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_025_001_o2.jpg?itok=C01hgXI9)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_025_002_o2.jpg?itok=iYulnYuv)

![[Untitled page from a sketchbook]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_025_003_o2.jpg?itok=LiWl1P8G)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2022_011_o2.jpg?itok=iPU5zabD)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2022_036_o2.jpg?itok=ZNmyK7iQ)

![[Study for monument to John, Washington & Emily Roebling, unrealized, Brooklyn, NY]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2022_024_o2.jpg?itok=67xPSx2j)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_009_V_o2.jpg?itok=YOUvzbAj)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_012_o2.jpg?itok=Irv-dCAc)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_014_o2.jpg?itok=xjWsNWUq)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_015_o2.jpg?itok=QPcVa8x2)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_016_R_o2.jpg?itok=fQP1FWpE)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_016_V_o2.jpg?itok=w1A_lqH-)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_027_o2.jpg?itok=GUokgmHZ)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_013_o2.jpg?itok=SJx0W1y9)

![[Underwater photograph taken in Bonaire]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2021_032_o2.jpg?itok=OLFaHV4G)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2021_031_o2.jpg?itok=bQiu4c4N)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2021_029_o2.jpg?itok=YIIh8lUk)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2021_030_o2.jpg?itok=L1VUpO5X)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2021_028_o2.jpg?itok=O6Vk2knj)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2021_027_o2.jpg?itok=c0pccUV6)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2021_026_o2.jpg?itok=CrY3a-CK)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2021_025_o2.jpg?itok=P4_ijkwR)

![[Underwater photograph taken in Bonaire]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2021_023_o2.jpg?itok=kZVvSWCw)

![[Underwater photograph taken in Bonaire]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2021_022_o2.jpg?itok=cNsjgYQw)

![[Underwater photograph taken in Bonaire]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2021_021_o2.jpg?itok=LaIFh_mT)

![[Untitled (Portrait of Marisol)]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/P2021_024_o2.jpg?itok=0RLl_y3C)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_094_o2.jpg?itok=RLOjUDzb)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2022_008_o2.jpg?itok=CBW_uKAR)

![[Study for monument to Juan Pedro López, 2000, Caracas, Venezuela]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_100_o2.jpg?itok=oYl8OsqX)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_101_o2.jpg?itok=Js2POu5I)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_103_o2.jpg?itok=J8JHRP6O)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_105_o2.jpg?itok=bF3GaKKU)

![[Study for monument to Emily, John, and Washington Roebling, unrealized, Brooklyn, NY]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_109_o2.jpg?itok=Nsh8aBJ0)

![[Study for "American Merchant Mariners' Memorial", 1991, The Battery, Manhattan, NY]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_126_o2.jpg?itok=c172-uZu)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_127_o2.jpg?itok=qeU5srtW)

![[Study for monument to Emily, John, and Washington Roebling, unrealized, Brooklyn, NY]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_129_o2.jpg?itok=-CMkoOXO)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_131_o2.jpg?itok=DEJBVYYp)

![[Untitled (Cat)]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_029_o2.jpg?itok=9Ld7Uzp5)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_058_o2.jpg?itok=F9aWVPDd)

![[cast bronze bird with red and black patina]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_065_o2.jpg?itok=ZF5y1iz7)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_084_o2.jpg?itok=qpuEyjh5)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_083_o2.jpg?itok=ydrAypVT)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_082_o2.jpg?itok=TDr55IkU)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_081_o2.jpg?itok=Nvz4eTe4)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_075_o2.jpg?itok=M6lbj7hH)

![[Untitled (doll)]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_073_o2.jpg?itok=3PICgsNG)

![[Study for monument to Dr. José Gregorio Hernández, Isnotú, Trujillo, Venezuela]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_069_o2.jpg?itok=XtNxQBF1)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_102_o2.jpg?itok=ptvGJ6bb)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_104_o2.jpg?itok=SnKb4Lm2)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_118_o2.jpg?itok=zF3BGQ4k)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_124_o2.jpg?itok=6YL08i2o)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_125_o2.jpg?itok=uYUOhhUX)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_130_o2.jpg?itok=VOpo26Ap)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_138_o2.jpg?itok=iYjwuoQY)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_085_o2.jpg?itok=JNb675e4)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_076_o2.jpg?itok=7OE_hqjS)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_077_o2.jpg?itok=Brs1gbep)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_078_o2.jpg?itok=L_FvyC8O)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_079_o2.jpg?itok=fFu0zXju)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_080_o2.jpg?itok=zWJY6vPw)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_086_o2.jpg?itok=iVQhW4lY)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_087_o2.jpg?itok=vxRhe52v)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_088_o2.jpg?itok=XubqLy13)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_089_o2.jpg?itok=kqoC66nS)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_090_o2.jpg?itok=w4K9_OKL)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_091_o2.jpg?itok=rILKJiih)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_092_o2.jpg?itok=S75boGml)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_093_o2.jpg?itok=kPkqF0JA)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_096_o2.jpg?itok=hCPioW1Y)

![[Untitled (study for monument to Carlos Gardel, Estación Caño Amarillo, Caracas, Venezuela)]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_039_o2.jpg?itok=8RaLxFG6)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_064_o2.jpg?itok=gkSHpvO1)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_070_o2.jpg?itok=G1EK6yLt)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_097_o2.jpg?itok=zB_uQzB2)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_117_o2.jpg?itok=Vf6HFIdB)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2021_031_a-c_o2.jpg?itok=qz4uIK9Z)

![[Untitled]](/sites/default/files/styles/callout_fixed_height/public/artwork/2023_003_o2.jpg?itok=RPJhzXwz)