By Julia Vázquez

Since I began working on the Buffalo AKG’s Marisol Bequest, I seem to hear many more ghost stories than I used to. In interviews, Marisol's contemporaries recall instances when her works seemed to come alive in the studio, falling over in the middle of the night and making noise out of nowhere.

Our own archivist, Gabrielle Carlo, regaled me upon my arrival at the museum with her own account of packing up Marisol’s books and papers: working in Marisol’s office late into the night, she saw her face in the mirror, seeming, as the hours passed, to change shape into Marisol’s own. As the months go by, I sometimes think that I see mine do the same.

The Marisol Bequest contains everything that was in the artist’s studio at the time of her death, like a freeze frame, or a Warholian time capsule. Marisol was known for portraiture, and for self-portraiture in particular; it has been difficult to go through the materials in the bequest without being reminded of this.

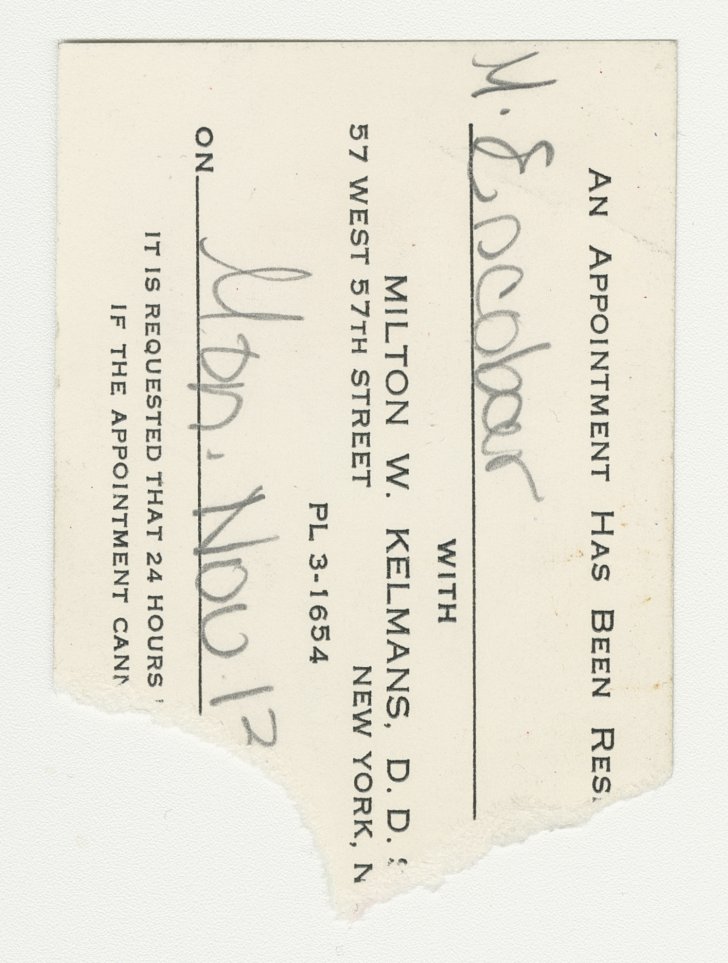

Portrait of the artist as a library, Portrait of the artist as a photo album: nearly every subsection of Marisol’s archive seems to replicate her in some medium or another. So much of the ephemera that I have pulled out of her books and boxes and file cabinets seemed random at first glance, be it a broken Barbie’s arm, or a doodle of a rose on a torn-up business card, or a postcard from some Tahitian destination. So little of it has turned out to be. Every fragmental ephemeron has added up to a collage that, puzzle piece by puzzle piece, merges together into yet another portrait of the artist.

Marisol, sketch of a rose, date unknown. Photo: Amanda Smith for Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York. Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery Digital Assets and Archives.

Marisol, sketch of a rose (verso), date unknown. Photo: Amanda Smith for Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York. Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery Digital Assets and Archives.

In her heyday, Marisol insistently incorporated casts of her own face or photographs in her sculptures, or images of her face formed in plastic, drawn in pencil, or carved straight from the block. She can appear as many as ten times, in ten different guises, in a single work of art. They give the most uncanny impression of presence, as though Marisol is hiding among her sculpted figures and might step out from behind them at any moment. Of course, she is never physically there. Marisol is present in her library, too, and in her photo albums, while also, maddeningly, never quite there.

“Para Marisol, con cariño”—“For Marisol, with love.” I saw this inscribed in more than one of Marisol’s books. Inscriptions abound in her books, in her letters, and on the backs of her photographs, with signatures like “Martha Graham” and “Robert Indiana.”

With each one of them, the cast of characters that populate the story of Marisol’s life and work comes, however blearily, into view. Others are scribbled so furiously that they’re illegible now. Nevertheless, each leaves a mark, like a handprint in Lascaux. Each signals the presence of another ghost, another story.