By Sherry Miller Hocking

Ralph and I first met you and Woody, your filmmaker husband, in 1971 in New York. We were investigating this new medium of video, along with a small group of other artists.

To set the cultural stage: Happenings, kinetic art, light shows, experimental music, conceptual art, mixed media performances, avant-garde film, process art, minimalism, materiality. All of the artists arrived at video from other arts disciplines—you from music, Woody from film, Ralph from photography and pottery. Others came from contemporary dance, experimental theater and the literary arts, or philosophy, religion and the sciences. There were no native-born electronic visual imaging artists. We were all immigrants.

To set the socio-political stage: the Vietnam war; political unrest, social campaigns for gender and racial equality, free speech, equal representation; sit-ins, protests at the universities, political activism ranging from passivism to violence. Public funding for the arts. Communes and collectives. Government-sustained programs for the well-being of citizens. A shared recognition of the importance of public support for the arts, education, and science.

In addition to this new art form itself, we were simultaneously inventing the institutions that could support it. You and Woody were at work creating The Kitchen, along with Dimitri Devyatkin, Andy Mannik, Michael Tschudin, Rhys Chatham, and Shridhar Bapat, among others. Ralph was transforming his Binghamton University–based Student Experiments in Television begun in 1969 into the independent nonprofit the Experimental Television Center, which by 1971 was based in a loft space in downtown Binghamton, an upstate New York community midway between Manhattan and Buffalo. The Kitchen’s primary program was exhibition. ETC offered studio residencies for artists and a research and development program, as well as workshops and other educational opportunities for the community around the region.

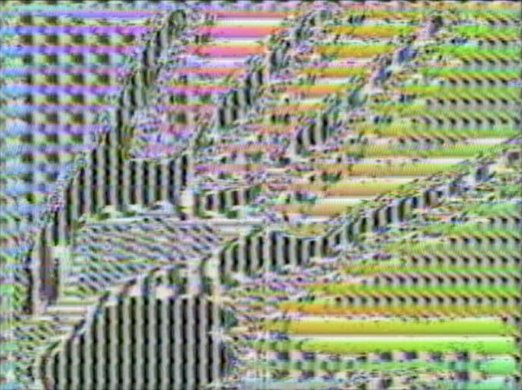

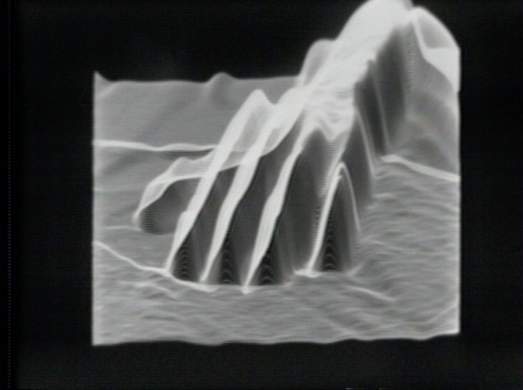

We were also inventing tools. The commercially-available primary instrument of video—the Portapak—was heavy, initially limited to black and white recording only (playback required a second deck), a limited battery capacity, and was relatively expensive; editing was initially physical and, when editing decks were introduced, rather imprecise. Commercial video equipment which expanded considerably on the range of possible imagery, devices such as mixers, switchers, and keyers were prohibitively expensive. Artists envisioned video images which had not yet been created. They partnered with technicians to realize these new systems which could bring these imaginings into the real world; they adapted and hacked existing tools and borrowed instruments from other arts and sciences such as oscilloscopes, audio generators, and synthesizers to bend images, warp frames, disrupt time-base, and to control various parameters of the image such as color or shape. Prerecorded images were created for specific sites and often involved sculptural elements or multiple monitor displays.

This was the environment of the new video works. There was no roadmap, no codification of the history, no stars, no acceptance by the art world. We were free to invent ourselves and our artform.

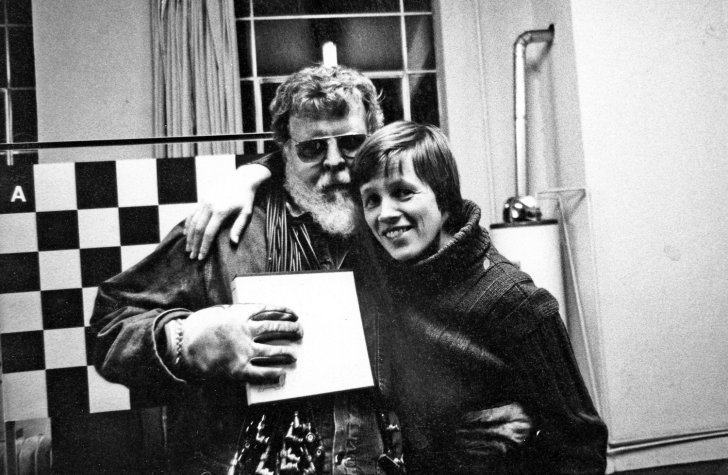

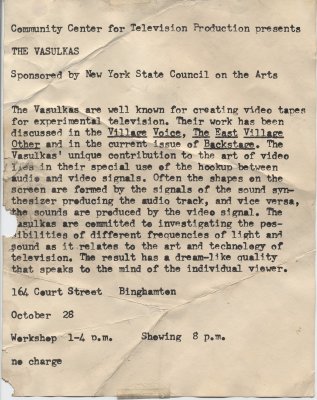

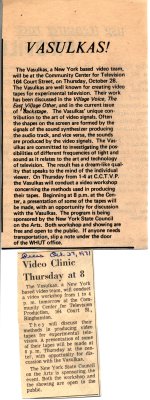

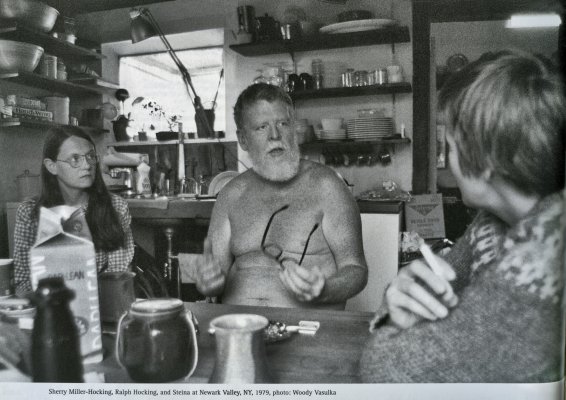

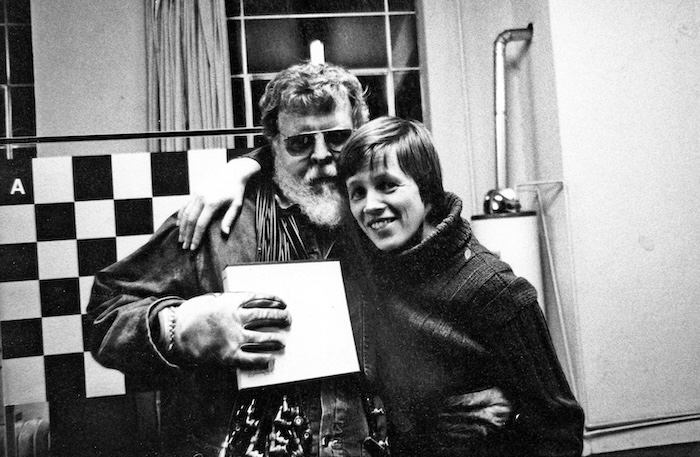

Ralph invited you and Woody to present work at the ETC in Binghamton in November of 1971. It was this visit that got us evicted from our loft space and prompted us to embark on a 50-year-long renovation of a small and rather ramshackle farmhouse in rural Tioga County, turning it into a home, a video processing studio, and a meeting place for several generations of media artists.

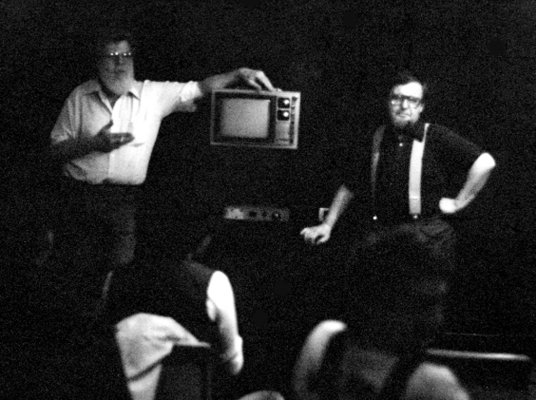

The Vasulka public exhibition attracted the university communities and local filmmakers, musicians, dancers and photographers. You and Woody broadcast live images in real-time and screened your videotapes on multiple monitors around the loft space. For people to see their own faces on tv was then an extraordinary event. All the rest of your work was astounding to the audience. To the best of my memory you showed a range of tapes. Participation contained documentary-style footage from the 1969–70 downtown art scene in New York: Jimi Hendrix, Andy Warhol, Jackie Curtis. Other works such as Studies and Sketches involved processed imagery and abstraction, along with electronic sound/music.

A lively discussion of the aesthetics of this new medium followed, an exploration of its essential grammar and syntax, and one of many which delved into the definitions of an art form.

After the event, we all went upstairs to the loft space Ralph and I shared to have dinner. You and Woody planned to stay the night, so we settled in cooking in a very rudimentary kitchen. Woody wanted sausages, so we bought a small hibachi and set it up at the bottom of a long wooden staircase leading to the roof which served as a fine chimney vent. The grilled sausages were delicious. We had a lovely meal, with conversation ranging from the design and construction of video machines and the studio spaces they populated and how these developments could best be supported, to the role of the university in the support of innovation in the arts. At the time, Ralph was a member of the Cinema Department at Binghamton University and Woody had yet to accept a position in Media Study at the University of Buffalo. The schools shared a commitment to independent film and an interest in the nascent field of video.

The next morning at breakfast the city building inspector responsible for the fire code enforcement surprised us with a visit to the building. The inspector took a dim view of the evidence of the previous evening’s feast and promptly evicted us from our home. Loft living had not yet become fashionable in Upstate New York. By Spring we had found an old farmhouse in rural Tioga county, and with a lot of work, and help from friends and family, we created a home and video studio which Ralph and I shared until his death in August 2024, and where I still live.

Over the years, we collaborated on exhibition and research activities. From 1976–78, we embarked on a shared project funded by the National Endowment for the Arts and the New York State Council on the Arts into the development of an LSI computer system interface to a video synthesizer. The research team included Dr. Don McArthur, Walter Wright and Jeffrey Schier. Ralph and I made numerous trips to the Vasulkas at their loft in Buffalo, for this project.

We participated in a joint exhibition of installations and photography at The Kitchen in 1976.

Steina exhibited again at ETC in 1978, where she showed some of her recent processed work to an audience of about 70 people, as part of the exhibition series Video by Videomakers co-curated by Peer Bode and Sherry Miller Hocking.

Pioneers of Electronic Art at Ars Electronica in 1992 at ZKM proved to be a massive undertaking. A comprehensive examination of the tools of electronic imaging, the show included the display of early instruments and systems many of which came from Ralph’s collection of early machines. The ETC, and Richard Brewster in particular, helped to design many of the interfaces which allowed the tools to be used by the audience: a living museum of antique instruments. In the Curatorial Statement in the catalog, Woody noted “ ...Ralph and Sherry Miller Hocking are the only collectors and archivists of many of these instruments. Ralph picked up the phone as if we were having an uninterrupted conversation over the years.” In later years, our focus with you turned toward issues of archiving and preservation, not only of tapes but more complex notions surrounding installation works and the instruments themselves.

In 2002, we invited both you, Steina, and Woody to participate in the conference we organized in cooperation with Mona Jimenez, Look Back/Look Forward: A Symposium of Electronic Media Preservation, May 31–June 1, 2002, organized by ETC in cooperation with Mona Jimenez held in NYC. You both joined Joel Chadabe in discussing the efforts then being made to preserve the instruments and artifacts of electronic imaging.

Along the way and through countless conversations we exchanged and refined thoughts on the definition and nature of the medium. What are the most productive ways to support research and development of tool design. How can we better recognize and support women and underserved communities who wish to work in technology. How can we address the critical need for electronic artists to have a personal studio where they could live—always—with the instruments of their art form. We shared our disinterest in the “art scene” and a respect for work that flourished outside the normal commercial channels of the art establishments; our suspicions about the influence of commercial interests on culture; the value of cultural work.

We swapped many tapes—many of them early sketches of video processed works. And in the later years, had many wide-ranging conversations about preservation, restoration, and history.

These events led to a lifelong relationship with you and Woody in which together we have witnessed and attempted to nurture a new art form. Thank you for the privilege of that extended conversation.

Sherry Miller Hocking has worked since 1972 with the Experimental Television Center (ETC), which provided an international media arts residency program, educational opportunities and sponsorship for independent media and film artists and projects. Hocking directed the Electronic Arts Grants Program, providing funding to individuals and arts organizations. Since 1994 she has directed the Video History Project, an online research database for media scholars worldwide. She has helped organize a number of preservation conferences, notably the Video History Conference at Syracuse University. With Kathy High and Mona Jimenez, she co-edited of The Emergence of Video Processing Tools: Television Becoming Unglued (Intellect, 2014). The archives of ETC are in the collection of the Rose Goldsen Archive of New Media at Cornell University.