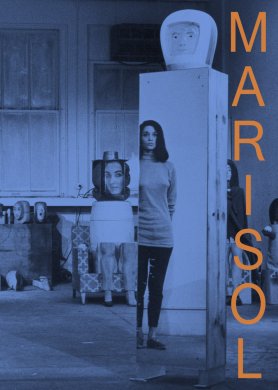

By Anna Scime

1. Sea and Sun (Water and Dreams)

A work of art is like a dream where all the characters, no matter in what disguise, are a part of the dreamer.

—Marisol

Among her rich and extensive archive—containing Marisol’s writings and films, over 100 sculptures, hundreds of works on paper, thousands of photographs and slides—my favorites are her fish and water works.

When they premiered at the Sidney Janis Gallery on May 3, 1973, Marisol’s fish and water works were panned by critics as “uninteresting, banal, even ‘meaningless.’”[1] Yet these pieces seduce me the most. They’re simultaneously the works of Marisol’s that are most ahead of their time and the works most firmly rooted in antiquity.

Perhaps this is why I’m also drawn to sturgeon—they’re ancient fish that promise us spring. I’ve always loved the water but it wasn't until I learned to dive that I fell in love with fish. I’ve been filming them ever since. And it wasn't until I first saw a sturgeon leap out of the rapids here at home that I realized how much magic and life our waters still contain. I’ve been filming them ever since.

Marisol’s fish and water works are exciting, self-assured and self-reflexive. They lure you in. The more I learn, the more I want to know. So who was Marisol? What motivated her?

Marisol's name literally translates to “sea and sun” when spoken aloud in Spanish (“sea”/mar “and”/i (y) “sun”/sol). Three musical syllables suspended in a balance of opposites. When she began to show her work publicly, she abandoned her surname (María Sol Escobar) and used only the nickname that her mother had given to her before she committed suicide. Sea and sun—a name that immediately calls to mind myth and legend. A blessing and a curse.

This name is situated in fraught territory and populated by a strong, innately felt imagination—the sun also rises and sets from the sea. It’s a place of paradox and a mixing of opposites; visible sometimes in the sun’s reflection on the surface of the sea, an image heavily featured in Marisol’s watercolor works. The sea and sun are sensual elements that can be seen, felt, and with the help of weather and other forces even heard, tasted, and smelt. Their presence is profound, and their absence is too.

Brought up with a lonely privilege and raised across the world—the sea separated Marisol’s many homes. She lost her first home (her mother), when she was eleven. She belonged everywhere and nowhere in particular after that—like sunlight or water.

I can speak from a place of some shared experience here, though my mother died quickly from a brain tumor when I was a teen. People heal but there are always holes and scars—you’re forever forgetting and remembering, and always searching for a place that feels like home. Perhaps people like us are instinctively attracted to water as well.

Echoes of Marisol’s physical presence are everywhere in her work. They’re alluded to through the tactility and textures of the materials that she selects and the creative processes that her pieces reveal. This presence is often literally imprinted in the work as well—drawn and cast from her face, hands, arms, breasts, legs, feet, sometimes her entire body (like a gyotaku). Many of her fish wear her face and her hands sometimes replace fins. All fifteen faces in The Party, 1965–66, both of the faces in Dinner Date, 1963, and The Wedding, 1962–63, four of five faces in The Jazz Wall, 1963, and the faces of Baby Girl and Baby Boy’s dolls are hers (1963 and 1962–63, respectively)—and many more of her faces and hands in particular appear in her work across decades and mediums.

As someone who worked in solitude much of the time, this was both a practical and a mimetic reflection of her reality. She spent a lot of time alone. She had come of age in mourning and largely in silence. At age eleven she stopped speaking. In her early twenties she started again. During that time, she found her voice in silence. She did what any artist would do—she made art.

2. Water Works (Mirrors and Liquid Logic)

Mirror impressions are hard flat images. They are unreachable images, but an image in water possesses infinite potential.

—Gaston Bachelard [2]

Marisol's mirror image is reflected and ripples across her larger body of work, and through its fractured repetitions, disrupts the illusion of the unified self. Because she uses her face so often in her work (and perhaps because hers is such a seductive face), she was often dismissed as a narcissist. However, I see her use of her likeness in her work to be akin to speaking in the first person, a sign of humility—as if to say “all I have to offer is myself.”[3] At once confessional and secretive, she hides and reveals herself simultaneously in her work.

Like most myths that survive Western antiquity, there are various versions of the story of Narcissus though there are always at least a few universals: obsessive self-love, fluidity in identity and transformation through death and desire (the Narcissus plant grows where he dies).[4] In one version, Narcissus becomes so utterly transfixed by his own image that upon trying to reach the object of his desire, he drowns himself in its container (In Ovid’s version he wastes away at the water's edge).[5] This version paints a portrait of a quick death wherein while attempting to penetrate the object of his desire, it penetrates him. It explores an active narcissism and a Janus-faced mirror that is “the Kriegspiel of aggressive love. . . [it] regrets and hopes, consoles and attacks.”[6] In this way, characters like Narcissus, the Undines, Charon, and Ophelia who are drawn from these root metaphors, transform water into a quintessential material with which to dream and to create.[7] Marisol does this too, and in all of these works the sea is both a womb and a tomb.

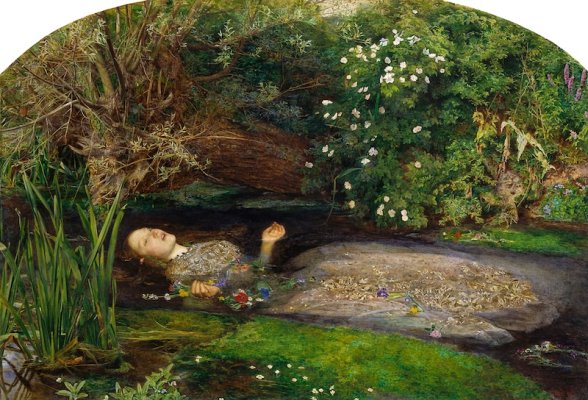

In the fish and water works with Marisol’s face, especially works like Greenfish, 1970 (above), which in all of its lush, liquid-green glory prominently features her hands and parted lips—I can’t help but see Elizabeth Siddal slowly sinking into the stream in John Everett Millais’s Ophelia. I could stare at this painting for hours. This painting is a film. Siddal was the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s collective muse, and their ideas of feminine beauty, mimesis and nature were fundamentally influenced and personified by her, but few read her poetry or appreciated her drawings and watercolors.[8] Ophelia almost killed her. After posing for hours in a tub filled with freezing water she became ill, developing the addiction for laudanum that would cause her death a decade later. Like Ophelia, cultural and political forces, critics and fans drove Marisol into the water. Unlike Ophelia and her most iconic model, Marisol adapts, evolves, and thrives underwater.

Water is roughly eight hundred times denser than air. Light absorption in water is dynamic. As water absorbs light, it filters out color. The deeper you dive, the more unsaturated colors become. Red has the longest wavelength and the lowest energy in the spectrum (ROYGBIV). It’s the first to disappear at depths as shallow as 15 feet/5 meters (OYGBIV). Next is orange, which starts to fade at 25 feet/7 meters, then yellow at 35 feet/10 meters (GBIV). If you cut your hand at this depth, your blood will be green. Blood green. Perhaps in this way Greenfish also references violence and depth. Green follows at 70 feet/20 meters. Then BIV, blue, indigo and violet are the last to go. They have the shortest wavelengths and highest energy, which is why (in addition to the surface reflecting sky) large bodies of water often appear blue. The deep blue.

Marisol was at the height of her fame when she withdrew from the West and its art worlds, and descended into the sea. In 1969, she traveled to Tahiti and learned to scuba dive. She continued to dive throughout her life and to create photographs and films of the underwater worlds that she visited with the intention of producing a documentary, like the films of Jean Painlevé or Jacques Cousteau. She wanted to be like a fish, so she made herself into a fish.

During her time underwater, Marisol saw fish with faces that were “human-like. . . in their expressive movements.” She saw fish that reminded her of other humans and herself. She once said “there are reefs where you see the same fish, and they get to know you. You can pet them and everything.” In addition to asserting the artist’s authorship and agency, the use of her face on her fish sculptures provides a point of entry, a familiar symbol of intelligence (a form of anthropomorphization), and an invitation for exchange.

Triggerfish I, 1970, Triggerfish II, 1972, Greenfish, 1970, Barracuda, 1971, The Fishman, 1973, Fishing, 1970 (left), and Fished, 1970, all wear Marisol’s faces, and these faces in turn mirror the discernible species' specific expressions and characteristics. Mouths are mostly agape to varying degrees,[9] as though freshly plucked from the water and still gasping for air—and some like Barracuda are clenched and lined with jagged, razor-sharp teeth. These Marisol-faced-fish not only reference the violence intrinsic to humans/nature, but are also perhaps her way of saying that she’s been a fish out of water her entire life.

Fish always reference water, even when featured outside of it. Marisol’s freestanding-fish are polished, precisely shaped and sleek with traceable contours, sharp points, and rounded curves. They allude to the way that light interacts with and within water, and harken back to the feeling of discovery beyond the reefs teeming with life, in the blue epoch—an abyss filled with life that is always hiding and revealing itself.

By the time Marisol began to dive, the ocean had been "refashioned into a field of battle," and subjected to nuclear testing, militaristic conquest, ecological exploitation, industrial pollution, waste disposal, and geopolitical control. The late 1950s and 1960s saw a rising public awareness about and resistance to environmental degradation in all of its abject forms.

This growing public pressure culminated in the establishment of the EPA in 1970, following the First Earth Day Demonstrations and public outcry over disasters like the 1968 and 1969 burnings of iconic Great Lakes rivers—Buffalo’s namesake waterway, Cleveland’s Cuyahoga, and Detroit’s Rogue.[10] The EPA’s early tasks included enforcing 1972’s Clean Water Act, which created a framework for improving physical, biological, and chemical water quality across the US in fresh, salt, and brackish waters. This perfect storm created “a new global imaginary in which urgent environmental preservation emerged as a possible antidote to nuclear annihilation.”[11]

3. Fish-Human Hybrids (Water and Imagination)

A truly poetic canvas is an awakened dream.

—René Magritte

Marisol’s fish works engage deeply with themes of ecological connectivity and interdependence, challenging anthropocentric hierarchies and the illusion of human separation from nature. They are also clearly a critique of reckless progress, pollution, and nuclear war.

Human-fish-hybrids have appeared in art and mythology across cultures for millennia, serving as symbols of transformation, and the relationship between humans and the natural world. Early art historical examples include Sumerian/ Babylonian depictions of Uanna/Oannes, a fish-headed deity and the first of the “Seven Sages”—fish-human-hybrids that symbolized wisdom/ science/ art. Egyptian myths of aquatic-hybrid-beings like Sobek the crocodile god or Rem/Remi, as Sobek was called in his fish phase,[12] were also tied to creation stories and represented Ra’s tears/fertility/water/crops.[13] In Ancient Greece and Rome fish-human-hybrids like the Nereids and Sirens represented the divine power of the sea, while medieval European art depicted mermaids as both alluring and ominous figures embodying nature’s unpredictability.

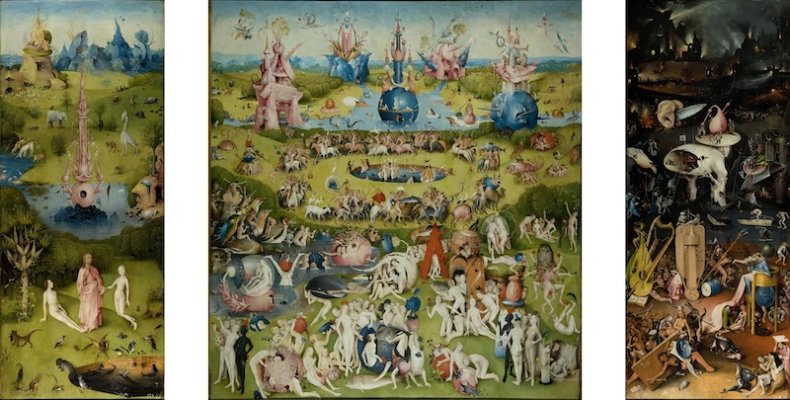

Renaissance works also brought these mythological figures to life.[14] All three of Hieronymus Bosch’s panels comprising The Garden of Earthly Delights, ca. 1490–1500, depict beautiful and grotesque fish-human-hybrids, reflecting anxieties about carnality/sin/chaos. Surrealist artists, like René Magritte, inspired by painters like Bosch and Giuseppe Arcimboldo (Italian, 1526–1593), reimagined fish-human-hybrids to explore psychosexual symbolism, absurdity, and the unconscious. In contemporary art, fish-human-hybrids often interrogate environmental, biotechnical, and evolutionary concerns—highlighting humanity’s fraught relationships and interdependence with other species and ecosystems.

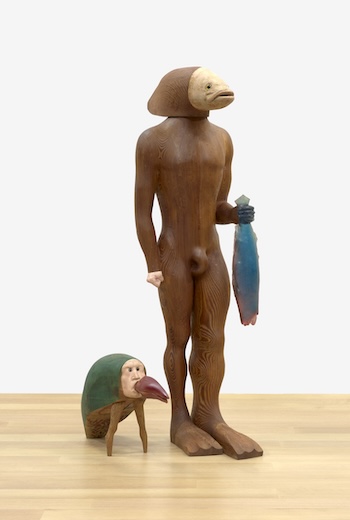

Marisol's The Fishman is complex and paradoxical—he attracts and repels. A collective assemblage, he and his pet harken back to antiquity, the Renaissance, surrealism, and the post-nuclear imagination, while simultaneously conjuring postmodern and contemporary explorations of hybridity, intersectionality, interspecies exchanges/ hierarchies, and a sort of mutant/toxic magical realism. The Fishman has been compared to mythological figures like Oannes, classical heroic representations like Greek Kouros, and post-nuclear-pop-culture-icons like Gill-Man from Creature from the Black Lagoon, 1954.[15] His pose references the symmetry of archaic Egyptian and Greek sculptures and stances, yet it subverts their heroic balance with his different-sized legs. The fishman’s imposingly horizontal head, which appears to be that of a bass, is uniquely reminiscent of Sobek’s/Rem’s/Remi’s. He simultaneously embraces and rejects archaic stylization, and blurs the boundaries between order and chaos, human and aquatic.

Though imperfect and asymmetrical—the fishman is gentle and beautiful. His kind, glassy eyes stare out from his profile and into the periphery, and his nude body is lovingly sculpted and designed. His face is pronounced—unvarnished, velvety-rough in the front, it stands out from the polished wood that makes up most of his body. One hand is partially blue where it connects to a blue fish wearing Marisol’s flesh-colored face, dangling tail-end-up. The other flesh-colored hand clenches a tight fist, or perhaps conceals a shell.

It’s difficult to encounter this figure without thinking of Magritte’s The Collective Invention, 1934, and its clumsily created mermaid: washed up on the beach, she’s presumably alive though stranded and seemingly in distress. What appear to be the head and fins of a grayling[16] are attached to shapely human legs and feet. She’s absurdly designed, and seemingly without function in the water or on land. Her body is scaleless and hairless except for pubic hair—a sexual lure. Magritte makes mockery of a male gaze typical of surrealism and the traditional mermaid, and through an inversion of the fish-tailed, human-headed form, renders it at once alluring and unsettling. Like Marisol’s fishman, Magritte’s mermaid transforms the familiar into the uncanny to reveal deeper truths about desire and identity.

Marisol’s fishman is more functional than Magritte’s mer-folk in the water and on land. However, his small sea-bug-human-hybrid companion is not, and it’s impossible to ignore the uncanny creature at this heroic-hybrid’s heel. With its crude green shell/ Marisol’s crossed-eyed scowl/ stick legs/ large red claw or beak extending from its mouth, it's quite a spectacle, and like Bosch’s fish-hybrids invites viewers to confront the absurdity and horror of a world turned upside down by human folly.[17] Both figures are complicated composites, and complimentary opposites that reference a rich and expansive set of symbols and figures from throughout art history.

In The Fishman the most monstrous parts appear to be human (and to come from her). Marisol’s mythic-hybrid-monsters embody complex cultural anxieties—they must be destroyed, or at the very least understood and empathized with. This piece entices the viewer to do both.

By invoking ancient myths, surrealist dreams, and post-nuclear realities, Marisol’s fish works compel us to confront humanity’s destructive tendencies and seek an empathetic view of ourselves and other species in the face of difference. Her fish-human-hybrids are neither fully monstrous nor wholly human. These hybrids reveal our connection to and enduring fascination with our primordial origins, and with water and its material imagination.

4. Movement Studies (Water and Sex)

How it feels to flow with water and its different corals and fish.

—Marisol

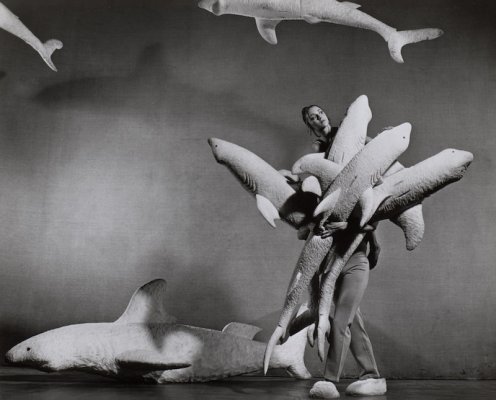

In 1970, Marisol designed costumes, responsive props, and decor for The Louis Falco Dance Company’s production of Caviar, 1970. It was her first foray into the modern dance world and collaborating with a choreographer, dancers, light designers, and musicians. As someone with a largely solitary practice, this kind of collective exchange was new for her, though she would work on eight more dance productions after this.

Caviar was erotic and energetic. An avant-garde multimedia-experience, it embraced precise choreography and technique, as well as improvisation and chance. Critics lauded Caviar as a “stroke of brilliance” (though dance fans were not as entranced).

Marisol fashioned life-sized sturgeon from fleshy-gray foam and rubber.[18] They shared a stage with eight barefoot dancers wearing blue textured material that created a connection to water and the fish that they animated with their movements. In the black and white analog video documentation, the fish-human connection is even more pronounced—twirls produce light and image trails and other artifacts, and these bodies bleed together when the camera fails to crisply capture their movements.

At times totemic and harkening back to her sculptural work, Caviar's fish-human-hybrid-dancers are bathed in chiaroscuro light as they leap, spin, collect, and disperse across the stage. Caviar is about sensuality, the character of the currents, and the art of collective motion underwater. While the dancer-fish may perform solo for a moment, disappear and reappear on-and-off stage, pair-off, break-apart, and form larger and smaller groups; at its core and despite its chaos, this performance is a cohesive, collective exchange.

For those of us privileged enough to see these creatures in the wild, Falco’s choreography was surprisingly perceptive, and echoed the movements and energy of the spectacle of the sturgeons’ spawn. Sturgeon collect in large groups to spawn in swift waters, swimming back-and-forth/ circling/ twisting around each other—leaping from the water—rubbing and touching each other with their bodies, barbels,[19] faces, mouths, and fins. They’re broadcast spawners—collective choreography may enable it, but conception (and survival thereafter) is ultimately guided by chance, and the water is quite literally an externalized womb. These collections of massive, ancient fish dancing in the currents are truly something to behold.

Caviar’s soundscape features audio of waves, water, and whale songs, remixed with psychedelic rock. Echolocation and other communications are mixed into modal melodies articulated by an electronic orchestra with solos and movements that mirror the dancers’ and draw a connection between the underwater world, sex, and psychedelic experience.[20] Fixed bodies/instruments/notes dissolve into moving, dancing structures that are liquid, abstract and liberated from their containers.

Sound is movement underwater.[21] Particles are closer together in water, and transmit vibration-energy much faster and further than in air. Sound waves radiate outward from their sources like ripples on still water. Depth and proximity to its boundaries also affect character and speed. The greater the depth, the faster and further sound waves travel. Near the surface psychedelic rock sounds more like drone—music that someone like Tony Conrad might play. Water obscures direction when you’re submerged as well. This is why we can sometimes hear sturgeon thunder. In the Great Lakes, Indigenous Nations like the Menominee still listen for this underwater “thunder” to announce the arrival of the sturgeon and spring. There are many old stories (even a pictoglyph) about this.[22] Sometimes I can hear them when I film.

In a contemporary context, Marisol’s sturgeon offer far less celebratory layers of meaning, and caviar is a culprit. As the extinction crisis rages on, fueled by the anthropocentric and destructive forces that drive contemporary capitalist culture, here in the Great Lakes sturgeon are largely extirpated from almost every waterbody in which they were once commonly encountered. At 1% of historical populations, and with the lightning-fast speed at which they’ve disappeared and the glacial, multi-generational speed recovery requires—they’ve become the quintessential aquatic symbol of the Anthropocene.

Today, they’re a rare sight anywhere in the world.[23] In Western New York, we are lucky to have two small, wild self-sustaining populations in Lake Erie and Ontario, separated by Niagara Falls.

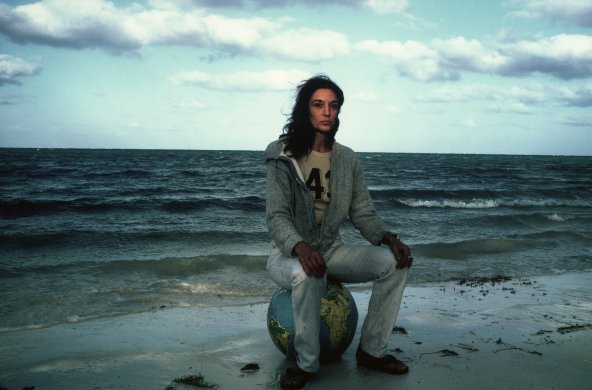

In the case of my film-in-progress—about these waters, ancient fish, time, nature and human nature—at its core I’m making a film about material imagination, phenomenology and its affective qualities. A film that translates the senses through cinema.

Among her rich body of work, my favorites are Marisol’s fish and water works. While very different, our work draws from the same material imaginations and mythological wells. Like Marisol, my work focuses on process as much as product, and echoes of my presence are palpable.

Water changes shape to meet conditions. Liquid in boundary, amorphous in form, water possesses infinite potential.

Anna Scime is an artist and filmmaker based in Buffalo, New York. She’s also a fish and water lover, and PADI certified diver (since 2009). Select pieces from her multimedia installation Lake Sturgeon's Guide for Surviving the Anthropocene will be on view as part of From the Great Lakes to the Great Plains: The Visible Current of Climate Change at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts in 2025. She is also in the process of completing a feature length film of the same name. You can find her on the web at a--a.org.

Footnotes

[1] Julia Vázquez, “Marisol Underwater, 1970-1973," Marisol: A Retrospective, 106.

[2] Gaston Bachelard, Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter. The Dallas Institute Publications, 2006, 22.

[3] As Chris Marker, one of French cinema’s most elusive auteurs famously said. Jonathan Rosenbaum, "Personal Effects: The Guarded Intimacy of Sans Soleil," Criterion Blog. Available: https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/484-personal-effects-the-guarded-intimacy-of-sans-soleil

[4] Theophrastus and Virgil both wrote about this particular species, which is native to Europe and North America. Virgil’s Eclogues tells the tale of Narcissus. It is also the flower that Persephone and her companions were gathering when Hades abducted her and imprisoned her in the Underworld. There are many species of Narcissus plant, all with extremely fragrant flowers, and all plants extremely toxic to consume. Many of the smallest species have become extinct, requiring vigilance in the conservation of the wild species.

[5] The differences between these two are the differences between active and passive narcissism. The difference between lack acted upon and lack suffered from a distance.

[6] Bachelard, Water and Dreams, 22.

[7] And those that tell theirs and similar stories across cultures, millenia, and mediums. There is an incredibly rich and varied material imagination and mythology concerned with water from across the world, cultures, and times.

[8] John Ruskin “proclaimed her a genius and bought all of her work” and Dante Gabriel Rossetti was her lover and she his “muse,” and later her husband at the time of her death. Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Walter Deverell and William Holman Hunt all painted Siddal. See https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/millais-ophelia-n01506/the-real-ophelia.

[9] Fish do this to help them breath, feed, and communicate. A fish mouth is the organ of respiration and feeding in fish. It is located at the anterior part of the body and typically has four parts: upper jaw, lower jaw, two sets of gill arches (the operculum), and a set of teeth. Fish mouth shapes play a critical role in the way they feed, interact and survive. Fish mouths come in many sizes and positions, each of which has a unique set of functions related to their environment.

[10] The Chicago River burned prior to this as well, as did others. See John H. Hartig, Burning Rivers: Revival of Four Urban Industrial Rivers that Caught Fire. Ecovision World Monograph Series. Michigan, 2010.

[11] Vázquez, 106.

[12] Donald A. MacKenzie, Myths of Babylonia and Assyria. Kessinger Publishing, (2004) [1915], 29.

[13] Rem (“to weep”) fertilized the land with his tears. Ibid, 30.

[14] Though without the appreciation of the ancients, and echoing medieval understandings and monotheistic interpretations of these archetypes.

[15] In the catalog to Marisol's Trisolini show, José Barrio-Garay compares The Fishman to the Babylonian fish-god Oannes (Oan/Oannes, Sumerian Uanna/U-An), while Vásquez makes the comparison to Gill-Man.

[16] Thymallus thymallus, sometimes referred to as “lady of the stream.”

[17] Moral allegory/chaos/metamorphosis/the unknown contributes to the unsettling presence of these hybrids. The water (and the lush garden that it references) would have also represented love or lovemaking in Bosch’s day.

[18] Depending upon the species, adult fish can be 3–25 feet long. The fish featured on stage in Caviar are about the size of the average adult fish found here in Western New York.

[19] Barbels are the four “whiskers” that descend in front of their face like a mustache are chemosensory organs.

[20] Caviar's music is composed and performed by: Pot with Napanaw's Pottery Shop Rock Group (Aldana, Gary King, Doug Arioli, Steve Tindall) and orchestra conducted by Eugene Lester.

[21] In water, the particles are much closer together, and can more quickly transmit vibration-energy from one to the next—they travel over four times faster than they would in air. When underwater objects vibrate, they create sound/pressure waves that compress and decompress water molecules as they travel through the sea. These waves radiate in all directions and away from the source like ripples on the surface of still water. Sound also travels faster and farther in the sea. Speed and distance depends on the density of the water (salinity/turbidity/ temperature/ depth) and the frequency of the sound.

[22] Sturgeon speak if you're lucky enough to be able to listen. They make “thunder” when they spawn. When I film these fish, I most often hear these sounds with a hydrophone just before milt or eggs are released. The people who have lived along the Great Lakes for millennia have long told stories about the faint drumming sounds and vibrations in the spring. Over the last decade, Western science has finally started to accept such accounts using their own metrics. See https://seagrant.noaa.gov/sturgeon-thunder/. This is what ecologists like Robin Wall Kimmerer and Neil Patterson Jr. mean when they talk about TEK/SEK (Traditional Ecological Knowledge / Scientific Ecological Knowledge).

[23] The populations in the Great Lakes went from millions of adult sturgeon in each Great Lake to less than 1% of the collective historical population in a few short decades. Female sturgeon reach sexual maturity when they are 16–30 years old, and will spawn once every four to seven years after that. Males mature at about 10–18 years, and generally spawn every other year. They are incredibly vulnerable during the spawn.