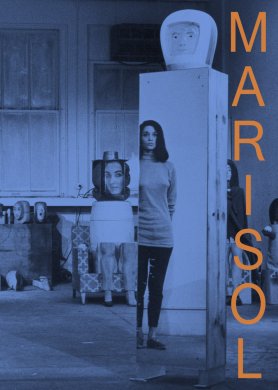

Jessica Beck is currently a director of Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills. In 2021, as The Warhol Museum’s Milton Fine Art Curator, she organized the exhibition Marisol and Warhol Take New York. It was one of the first major exhibitions after Marisol’s death and it helped reintroduce the artist in the context of her work alongside Andy Warhol in American Pop art. Editor Matt Connolly spoke to Beck about that exhibition and the significance of Marisol and Warhol’s relationship.

MC: To start, could you tell us a little about your background and how you came to be interested in Andy Warhol?

JB: I actually grew up outside of Pittsburgh, and I visited the Warhol Museum frequently growing up. The thing that imprinted on me from all those visits—and the kind of special thing that happens at the Warhol Museum—is that you get a sense of the person behind the myth. One of the great gifts that the collection has is both the film material, all of the films that Warhol made during his lifetime, and then all of this archival material, so you really get a sense of the complexity of who Andy Warhol was.

MC: What was it like being a teenager in Pittsburgh and going into the Warhol Museum? Do you remember what caught your imagination about the artist?

JB: I had taken this high school trip to Italy, and we had one of those ten-day bus tours where you're in Rome and then you're in Florence and then you're in Capri on this little bus. I had convinced my art teacher to take one of these trips, since he was retiring. On the day that we were in Florence, the tour did not have the Uffizi scheduled, so I asked if I could go by myself because I really wanted to see The Birth of Venus. And there I had this transformative art experience. I talked to my art teacher, and he asked if I had considered studying art history.

So I went back home, and I went to Pittsburgh and was at the Warhol Museum, and I realized Warhol had made these paintings after Botticelli in the ‘80s when he was doing his Renaissance series. I just started thinking about who Andy Warhol was and what he was about.

MC: Do you remember what was so striking about him or his work?

JB: The strongest thing that came from those visits and the thing I’ve always locked in with him is the really intense play that he does on intimacy. There's always a tension of where the camera is, how close it is to the subject, how comfortable the subject is in front of his camera. He's always, always tinkering with that. That was my takeaway at that moment as a teenager: thinking of him as not this cold or manipulative machine, like, “Oh, wow, he's really using the camera in such a fascinating way to probe into the subject.”

MC: How did the concept behind Marisol and Warhol develop?

JB: The eight years that I was at the Warhol Museum, I was able to dive deeply into the collection. I've always been interested in the untold narratives within Warhol’s practice. There had been a small show at the MCA Chicago in the 2000s of a few works from their collection, and I think they had a few loans. There had never been this really in depth look at the two of them, and specifically into those early films, of which for many, it turns out, Marisol was a protagonist. At the time I had no idea that Marisol was in all of Warhol's 1963 films, and why didn't I know this? What else is in the archive? So that's where all the research started back in 2015.

MC: What was it like beginning to take stock of Marisol in film?

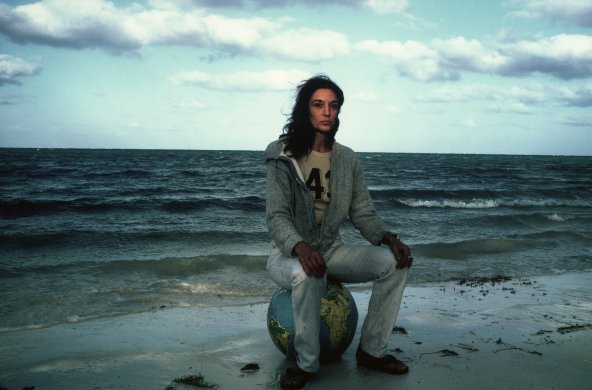

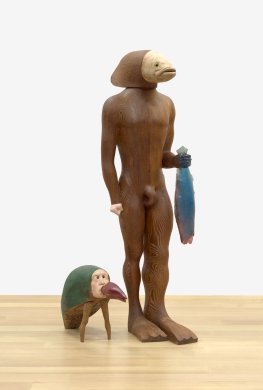

JB: I had known of Marisol's work, and I had in my mind a photograph on my phone of her sculpture Women and Dog from the Whitney. A colleague at the time at the Warhol Museum, Ben Harrison, who is the Performing Arts curator at the museum, does these great programs where he takes a Warhol film and pairs it with musicians. So he had done this series called Exposed: Songs for Unseen Warhol Films, and he invited musicians to do scores for a selection of film that had recently been digitized. Two of the films had featured Marisol, and this performance was at the Carnegie Music Hall in Pittsburgh, so the screen was really large. And I just remember sitting in the audience and being struck by, one, how beautiful the films were and how unique they were for Warhol, and then two, how striking she was in front of Warhol's lens. And then the interaction between the two of them—you can tell something unique is happening. So all of that sparked in my mind: “What about Marisol?”

MC: What was their relationship like?

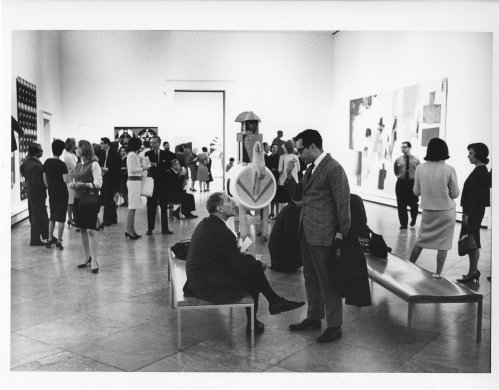

JB: The art world's always been its own fascinating ecosystem, and it can still be elitist in these intimate circles. And Marisol was very much at the center of these movements in New York.

Thinking about Marisol's presence in the press around 1961, ’62, ’63, this is a breakout period for her in the media and how she is presented in the media. Warhol in 1961 to 1963 he's really trying to navigate who he is as an artist. He presents as an exhibitionist, someone that's confident manipulating his image and confident with his presence in the world, but it's actually quite the opposite. He made a concerted effort to create essentially a mask, which is another fascinating connection back to Marisol. At the time that they meet, he is trying to figure out how will he present publicly, and for him, it's always connected back to navigating how to operate in this world as a gay man at a time when—in the 1950s—it's illegal. And by this point, Marisol had already had achieved that central fame, that spotlight that he was interested in and aspiring to have. I think he admired Marisol for what she was able to achieve, and then how successfully she navigated these inner circles of the New York art world.

MC: So by the time they met, she had already kind of figured it out in a way, or she had at least one version of her personality to present?

JB: The fascinating thing about Marisol, at least from how I read it from afar, is that she was very good with boundaries. She always understood how much she wanted to give and never apologized: “I am going to give you this much, and that's the end of it.” The difference in the two of them is Warhol's always chasing after something, whether that be more money, more success, more spotlight. He’s trying to always be in the center somehow. And Marisol always seemed to be very grounded and firm and let things kind of orbit around her, rather than chasing after them. I think that was probably the energetic pull for Warhol, because that kind of energy would be something that he probably aspired to.

That’s especially important at that time when the press is typecasting her as this glamor girl and challenging her femininity. In the same way that Warhol's dealing with how to present in this masculine world, she's also dealing with, “Why is she not married? Why does she not have children? Who is she dating?”—all of these questions that are repeatedly asked over and over again in interviews. She has that moment where she gets this initial spotlight and success, and then moves to Italy. She takes a break, continues to make work, and then moves back. So even at this young age, she just always reads as very strong.

MC: I love that way of looking at her, because there's a way reading it like she ran away as if she couldn't take it or something like that. But I like your kind of positioning of her as she just didn't want that.

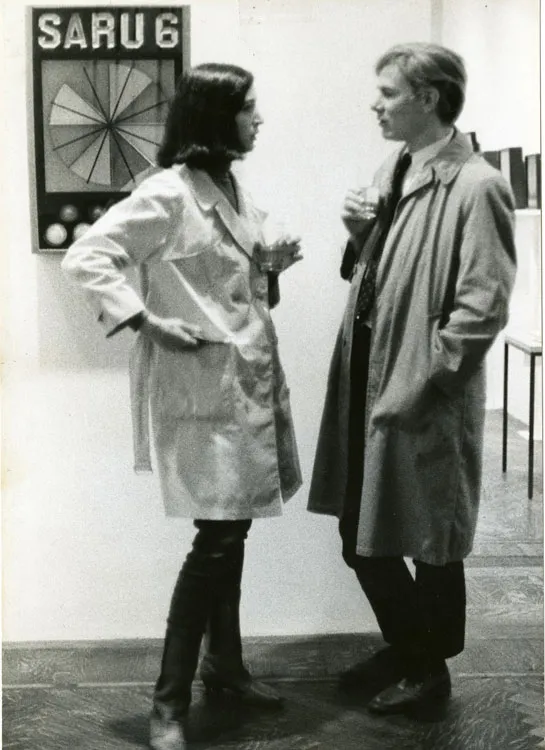

JB: There's this famous quote that he says, Marisol is “the first girl artist with glamour.” For him, that word means power. One of his first commissions in New York for ad illustrations was for Glamour magazine, and the article is about how to be a successful woman. In many ways, this idea of feminine glamor was a powerful thing for him. It was a sense of being self-possessed, of having a certain confidence, being able to navigate these power circles, being able to balance–and so he saw in Marisol that force, and it comes across in the films too. Her Screen Tests are incredibly powerful. Many people have written about the complexities of the Screen Test and how certain people buckled under the intensity of the lights and the intensity of the camera. And Marisol stands so strongly against the camera's lens, to the point that she's almost stone still.

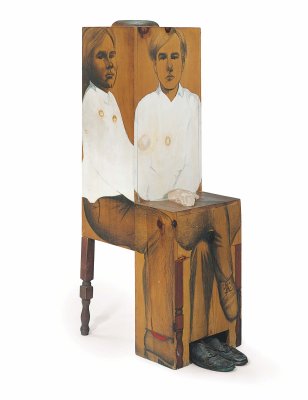

But what I love the most, in the film they did together Bob Indiana at Eleanor Ward's summer home, in Lyme, Connecticut, is the play. There's lightness. That’s also what she had in her, and she brings that out in Warhol. They brought it out in each other. Her portrait of Warhol, Andy, from ‘62–‘63 is so amazing. It just captures this really tender moment when he is wearing his collared shirts and his like laced up shoes and his belt and trying to come out of being an ad man in the late ‘50s to be a famous painter. He's still in that in-between moment for him, and she just captures him so poignantly.

MC: On a more personal note with the two of them, what happened to their friendship after this period of collaboration.

JB: With Warhol, there were these moments where friendships were so much of his work and his intimate life overlapped. Like anyone, we're closer with certain people at certain points of our lives. There was an intense moment between the two of them. And then, like with any friendship, things just shifted around, but they're still in each other's lives.

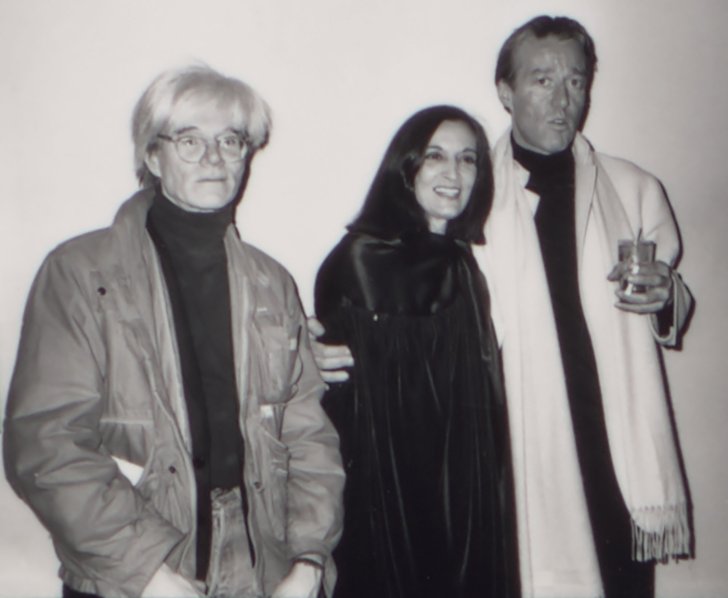

I couldn't get fully into it in the book, but they do remain friends in the ‘80s. There's a mention in the diaries of Warhol, one goes to the other’s birthday. And then they are featured on a special about Carly Simon recorded for a show called Omnibus on ABC in the spring of 1980. The contact sheets are viewable on Stanford's website and there is a brief clip on YouTube. Warhol writes about this in the diaries. He took photos of Marisol in the green room, and then he recorded on tape cassette this conversation before they were miked, and Warhol's asking Marisol about her painting materials. They're artists talking to each other as artist friends. He asks her how she's doing and she talks about how she goes around the city by herself, and he asks her how she gets home at night, that kind of thing.

MC: That’s somehow very heartening to hear, especially looking back on Marisol long life in the arts.

JB: This retrospective is so important and well deserved. Marisol was a brilliant, creative force and I'm thrilled that audiences will finally get to see the span of her career and experience her exceptional talent, which Warhol admired so much. It's about time!

Warhol's Screen Test for Marisol is on view at Marisol: A Retrospective at the Buffalo AKG Art Museum. Be sure to see the exhibition before it closes on January 6.