By Stephen Fredman, Professor Emeritus, Notre Dame

I first encountered Presences: A Text for Marisol at the legendary Moe’s Books in Berkeley, shortly after it was published in 1976. Like many of my peers in the poetry world at that time, I found it a very exciting combination of prose poetry and visual art, and it became a primary text for my first critical book, Poet’s Prose: The Crisis in American Verse (1983, 1990). I have always recommended it to friends and students and was thrilled when the University of New Mexico Press reprinted it recently in a new, larger-format edition, which includes photocopies of items from Creeley’s own library, especially postcards from Marisol to Creeley and drawings she made for him.

As a poet, Creeley was remarkably generous in opening up his writing to other artists. In fact, he considered creative alliances integral to the making of art, stating, “Poetry is a team sport: you can’t play it all by yourself.” [1] Regardless of whether their collaboration with Creeley began with text or artwork or was a simultaneous effort, many artists have testified gratefully to the easy working relationship they had with him and to the sense that he “got” what their art was about. As Francesco Clemente puts it, “Part of my fascination with these particular collaborations is how every time he seems to perceive what the form of the work is. He invents his own corresponding form that somehow has the same structure.” [2] Confirming this, Marisol wrote in a letter to Creeley after receiving the text for Presences, “It is really amazing how you could do something so close to me from seeing me so few times.” [3]

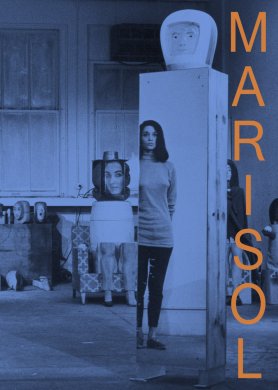

The collective artwork that became Presences owed its genesis to an earlier team effort, the sumptuous Numbers by Creeley and Robert Indiana (1968). As the poet recalls, “‘Presences’ began with the publication of ‘Numbers’ insofar as the sculptor Marisol had seen that collaboration with Robert Indiana and myself, and considered I might be the appropriate writer of a text to accompany photographs of her work, which a New York publisher had then in mind to bring out as a book.” [4] The designer William Katz was instrumental in both publications, inviting Creeley to compose Numbers with Indiana and later drawing Marisol’s attention to that gorgeous, large-format volume, with Indiana’s brilliant silkscreened numbers and Creeley’s poems in bold, sanserif type, printed to museum standards by Domberger Editions in Germany. [5]

The 1971 plan for a Marisol project was to produce not a limited edition like Numbers but an impressive coffee table book with reproductions of Marisol’s sculptures, to be published by Harry Abrams. Says Creeley, “It began as a book for Abrams. There was a great moment when I was given a thousand dollars as an advance, and I sent the text and nothing happened. Then I got a letter saying they really couldn’t do it. Their editor had advised them that it was just random stuff taken from the writer’s wastebasket.” [6] Katz hurried over to see Abrams, whom he knew, insisting the text was a powerful work of art in its own right. When the publisher refused to budge, Katz finally asked him, “Have you read it?”

"No. I don’t have time to read all the books I publish. I just publish them.”

At this point it fell to Creeley to take the next step. His trade publisher at the time, Scribner’s, undertook to print it with black-and-white images of Marisol’s sculptures, in the trim size they used for his poetry (approximately 5.5 x 8.5 inches). When Presences: A Text for Marisol saw the light of day in 1976, its design was unique: it lacks pagination; every page, of both image and text, is bled to the edges (including the gutter); and a photograph faces every page of text—but staggered, so that recto and verso pages of text follow recto and verso images.

In Presences Creeley sought to mirror in writing Marisol’s activity in sculpture. As he explains, “What we both wanted, then, was an active complement, rather than a descriptive prose text and/or a sense of illustration in the images themselves.” [7] The prose of Presences has many varied textures, through which Creeley explores “a diversity of senses of human ‘presence,’ in a diversity of modes, e.g., everything from tape ‘cut ups’ to almost nostalgically familiar ‘narrative.’” In one section, for example, he uses “a postcard of a reproduction of Poussin, plus the German well-wisher’s message at the back, plus the random ‘voice’ of a radio playing in my shed, etc.” As the examples of “cut ups” and of found text and overheard speech might suggest, one way to consider this prose would be as assemblage, and in this sense its method mimics closely the assemblage technique of Marisol. Such avant-garde methods, Creeley claims, should not be seen as ends in themselves but rather as means to investigate personal and interpersonal situations: “At the root, however, is insistently Marisol’s own preoccupation with terms of being human, and its various possible ‘representations’” (Letter to Kinsey).

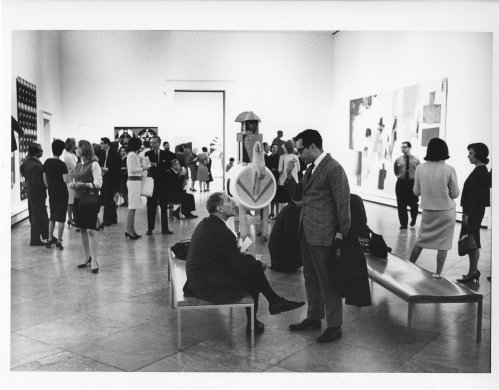

The photographs in Presences, arranged by Marisol and Katz, give evidence of a further turn in the feedback loop. Two of the sculptures, Baby Girl (1963) and The Generals (1961-62), were seen by Creeley in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery while he was teaching at the University at Buffalo. Other encounters with Marisol’s art took place mainly through Marisol, a 1968 Venezuelan volume she sent him and whose double title page she illuminated and signed. [8] “Finally, when the book was in proof, Bill Katz told me that one evening in company with Marisol they put all the page proofs and photographs on the floor, and decided on the appropriate juxtapositions. She also is responsible for the decision to ‘bleed’ the prose pages, so as to keep some textural balance with the ‘bled’ photographs. It was my decision to have an image always facing a page of text” (Letter to Kinsey). Thus, the monumental frontality of Marisol’s sculptures matches pages of text that have a similar visual effect, as if the blocks of Creeley’s prose poetry were things that fill space like the assemblages Marisol built up from blocks of wood. Including the covers of the book, there are photographs of thirty-seven of Marisol’s sculptures, with from one to four views of each piece. In these photographs, as in a technique from independent film, the viewer is often brought in close for a detailed perspective but never allowed to pan out to get an installation view of larger bodies of work. John Yau notes, “This lack of an overriding perspective parallels Creeley’s writing, its accumulation of details and palpable perceptions” (In Company 71). Every aspect of the making of the book promotes immersion in Marisol’s art and in Creeley’s language.

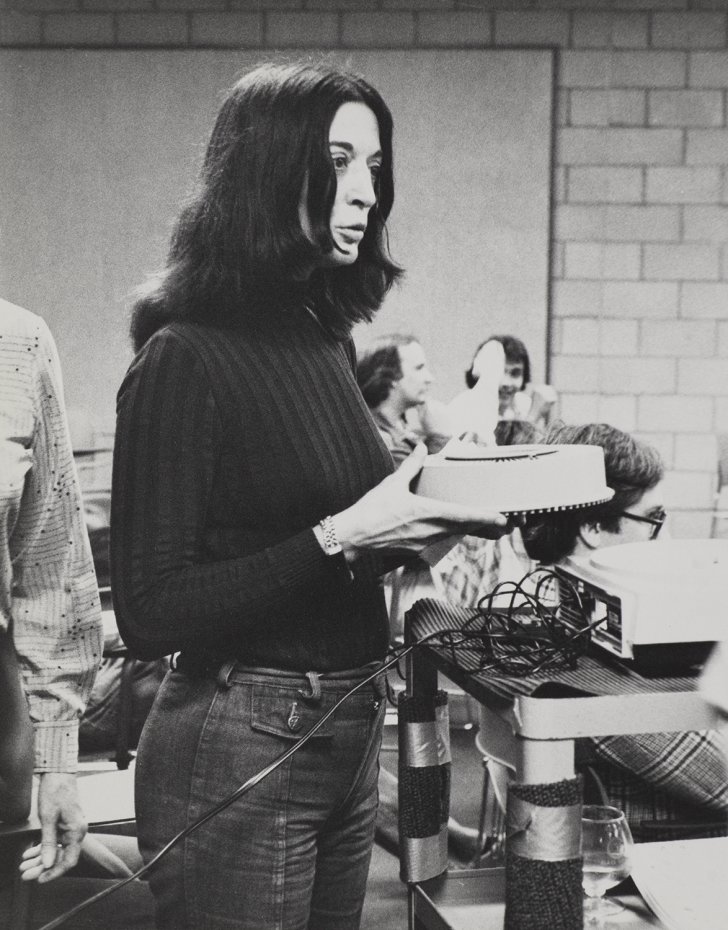

Balancing her interest in public figures such as the Kennedy Family, the British royal family, Lyndon Johnson, John Wayne, and Bob Hope, Marisol often concentrates in her art on intimate personal details—especially those of her own body. She casts her face and body parts for inclusion in many of her sculptures, even those not ostensibly autobiographical. Initially, she suggests self-portraiture is a mere expedient: “I’m always there (in my studio) when I’m working. I work very often late at night. I can’t call up a friend at one in the morning to make a cast of his face.” [9] She goes on to admit, however, that incorporating herself is actually essential to her art:

“Whatever the artist makes is always a kind of self-portrait. Even if he paints a picture of an apple or makes an abstraction. When I do a well-known person like John Wayne, I am really doing myself.”

Marisol’s act of measuring herself against or as part of everything she portrays has great resonance for Creeley. It bespeaks an existential commitment he values so highly that in an essay, “Inside Out: Notes on the Autobiographical Mode,” he quotes Marisol as authority on autobiography: “The sculptor Marisol speaks of using herself, over and over, in her work. ‘When I show myself as I am I return to reality.’” [10] In the final section of Presences (V.1), Creeley plays with phrases by Marisol that reflect her belief that self-placement is necessary to representing the world accurately. Creeley collages together words from Marisol, which he employs again and again as something like mantric phrases: “I return to reality. I had no other model. I used myself over and over. I put things where they belong. I show myself as I am.”

At the most basic level, Marisol is an artist of assemblage. In an interview with Creeley, Kevin Power makes explicit the connection between the variety of materials employed by Marisol and the variety of verbal modes in Creeley’s prose. He asks, “In the Marisol text are the presences, like the Marisol figures, facets of your various concerns e.g. language per se, the imagination made actual, autobiography, the role of pronouns, etc?” [11] Creeley agrees, affirming that senses of presence he shares with Marisol result from combining disparate materials to create an experiential assemblage: “Yes, presences, just dimensions of human presence, occasions of human presence, modes of human presence. I was trying to get hold of different kinds of experience of presence. It’s a situation that lets you ring the changes!”

He rings the changes right from the beginning of Presences: “Big things. And little things. The weight, the lightness of it. The place it takes. Walking around, it comes forward, or to the side, or sides, or backward, on a foot, on feet, on several feet” (I.1). Here the “dimensions of human presence” invoked by a Marisol sculpture provoke a meditation on conflicts of scale and how to orient oneself with respect to an object. In constructing the book, Marisol makes the right identification of images to match with this section of prose: two views of the gigantic Baby Girl (1963), 74 x 35 x 47 inches. This is one of the pieces Creeley saw in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, and it made a powerful impression. The reversals in Creeley’s prose seem to represent his coming to terms with stark reversals in the sculpture, where a huge, seated baby (over six-feet tall) dwarfs her mother, a diminutive doll adorned with Marisol’s face. Creeley takes at “face-value” this topsy-turvy world, registering the overwhelming, contradictory feelings it provokes. As the reader mentally “comes forward, or to the side, or sides, or backward” to assess the prose, one sees that on the page it too has an outsized and block-like quality, echoing the baby’s blockish head and boxy body. In the work of both artists, an improbable combination of horror and humor lends a disorienting, confrontational quality to their approaches to everyday life, requiring that the reader or viewer come to terms with unanticipated shifts in scale and materials as modes of presence.

Stephen Fredman taught in the English Department at the University of Notre Dame from 1980 to 2017. He served as Director of Undergraduate Studies, the Department Chair, and directed the Arts & Letters Core Course. His main field of expertise is modern American poetry and poetics. He is the author of five monographs, including Poet's Prose: The Crisis in American Verse (1983, 1990) and American Poetry as Transactional Art (2020), and has edited four volumes of critical work. Currently, he is at work on a memoir and a study of the impact of John Dewey’s philosophy on American poetry and performance art.

Footnotes

[1] Barbara Montefalcone and Anca Cristofovici, eds., The Art of Collaboration: Poets, Artists, Books (Victoria, TX: Cuneiform Press, 2015), 27.

[2] Amy Cappellazzo and Elizabeth Licata, eds., In Company: Robert Creeley’s Collaborations (Niagara Falls, NY: Castellani Art Museum of Niagara University; and Greensboro, NC: Weatherspoon Art Gallery, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 1999), 26.

[3] Marisol Letter to Creeley, May 1972, Robert Creeley Collection, Hesburgh Library, University of Notre Dame.

[4] Robert Creeley, Mabel: A Story and Other Prose (London: Marion Boyars, 1976), 5-6.

[5] Robert Creeley and Robert Indiana, Numbers, ed. Dieter Honisch, trans. Klaus Reichert (Stuttgart: Edition Domberger, 1968).

[6] Creeley, interview with Elizabeth Licata, Nov. 21, 1998. Amy Cappellazzo and Elizabeth Licata, eds., In Company: Robert Creeley’s Collaborations (Niagara Falls, NY: Castellani Art Museum of Niagara University; and Greensboro, NC: Weatherspoon Art Gallery, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 1999), 15.

[7] Letter to Marjorie Kinsey, 23 October 1976, Robert Creeley Collection, Hesburgh Library, University of Notre Dame.

[8] José Ramón Medina, Marisol, photographs by Jack Mitchell (Caracas: Ediciones Armitano, 1968).

[9] Quoted in Leon Shulman, Marisol (Worcester, MA: Worcester Art Museum, 1971), n.p.

[10] The Collected Essays of Robert Creeley (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 561.

[11] Kevin Power, Where You’re At: Poetics & Visual Art (Berkeley, CA: Poltroon, 2011), 114.