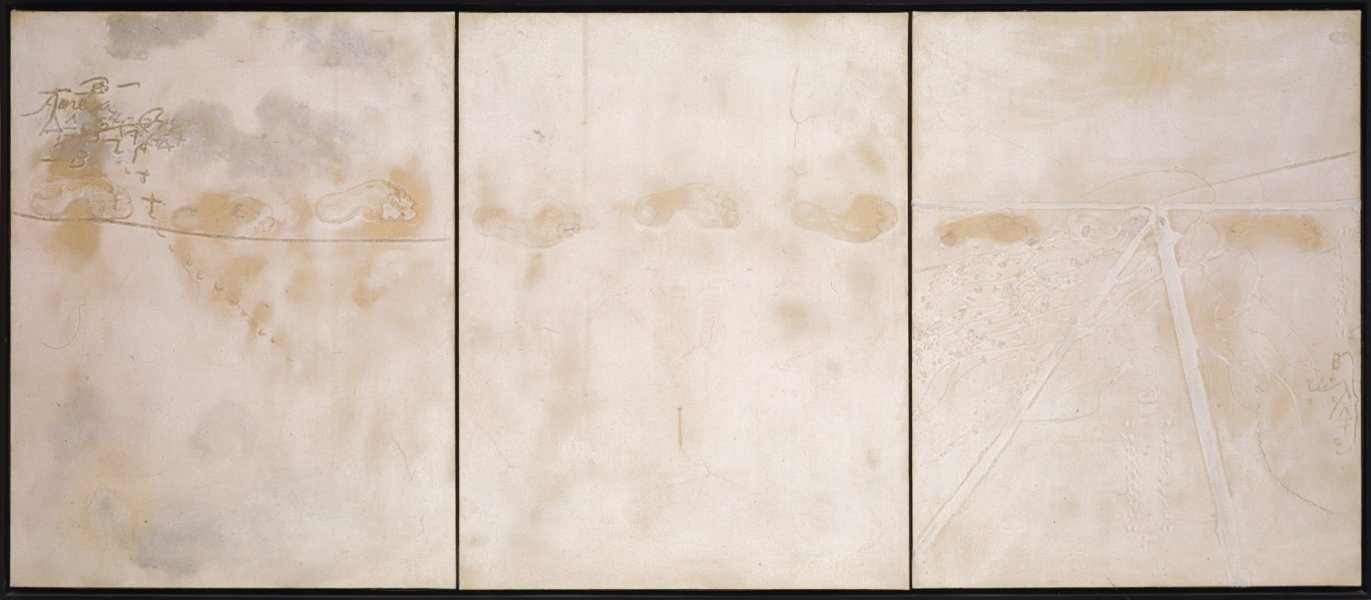

Polly Apfelbaum

American, born 1955

Reckless from the series "Fallen Paintings", 1998

Artwork Details

Materials

synthetic velvet and fabric dye

Measurements

installed dimensions variable

Collection Buffalo AKG Art Museum

Credit

Elisabeth H. Gates Fund, 2004

Accession ID

2004:23

For someone of my generation—going to school in the late 1970s—sculpture stood for three things in my mind. First of all, immediacy. Sculpture was something you walked around, took in as much with your body as with your eyes. Sculpture was physical, concrete. But sculpture in those days was also the privileged space for conceptual work. Finally, sculpture gave one permission to work outside of established categories, with materials not usually associated with artmaking.

It’s hard not to refer to Rosalind Krauss’s prescient article “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” from 1979, although her academic approach was never so close to mine. Krauss talks about the way in which sculpture became such an elastic category during the 1970s that one no longer knew what exactly it was: “And so we stare at the pit in the earth and think we both do and don't know what sculpture is.” Instead, she suggests, “we know very well what sculpture is. And one of the things we know is that it is a historically bounded category and not a universal one.” Sculpture, she says, ”has its own internal logic. . . . inseparable from the logic of the monument.”

Today—more than thirty-five years after Krauss’s article was written—the stakes are different. The idea of being bound by categories—sculpture or painting—is not so urgent, and I borrow from the logic of painting as much as from sculpture. Maybe one reason for the power of women artists during the '70s, like Lynda Benglis, Eva Hesse, and Jackie Winsor, is that they didn’t want to be constrained by historical categories because, as women, they knew how limiting that could be. Sculpture for me is certainly not about commemoration or monumentality, but it involves memory. In some sense Reckless is the opposite of monumental—it has no fixed form and changes every time it is installed. It has a promiscuous relationship to time. Reckless, as the word implies, is a reckless disregard of history and categories.

—Polly Apfelbaum, April 2016