Aldo Tambellini

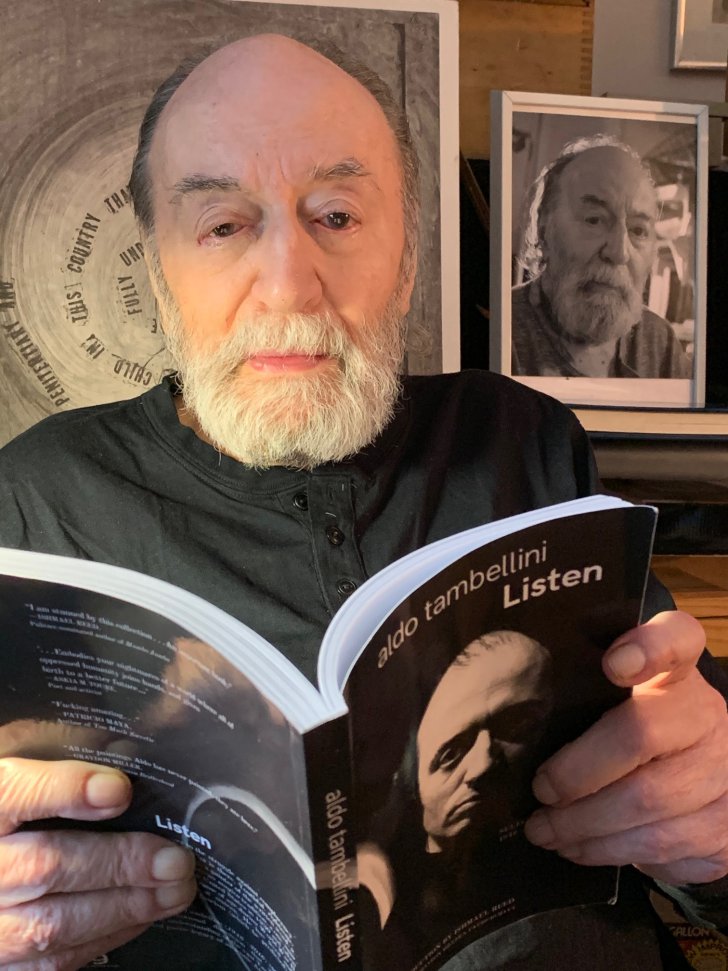

Image courtesy the Aldo Tambellini Art Foundation. Photo by Wendy Payne.

Although he has worked with almost every artistic medium, Aldo Tambellini’s most important innovations are in the realm of media art, which he helped pioneer in the 1960s. Born in Syracuse, New York, the artist and his family moved to his mother’s native Italy when he was just a toddler. A childhood under the regime of Benito Mussolini led him to become a lifelong opponent of fascism and advocate for political and artistic freedom. Following World War II, he returned to the United States to study, earning his BFA in painting from Syracuse University in 1954 and his MFA in sculpture from the University of Notre Dame in 1958.

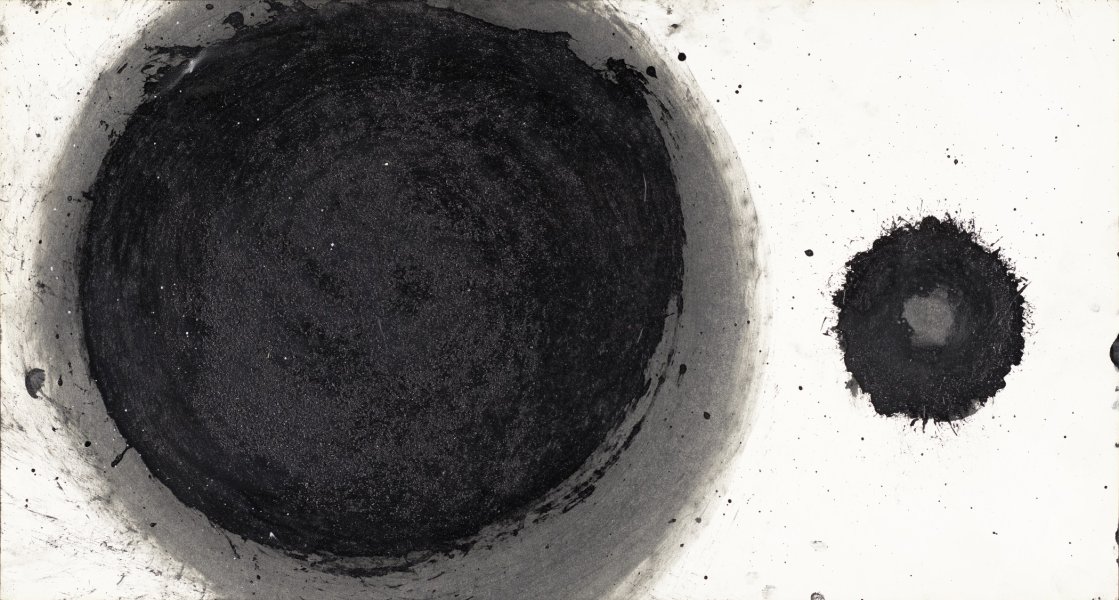

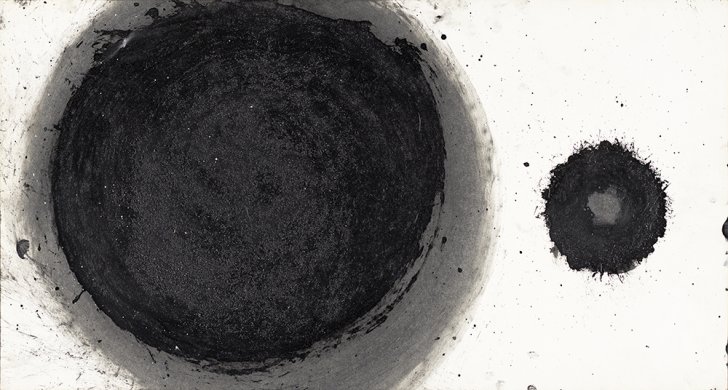

In 1959, Tambellini moved to New York, becoming a key member of the bohemian downtown art scene. It was during this period that he established a career-defining interest in the color black, which he understood as representing “the beginning of everything.” As he explained in a 1967 interview: “Black is a state of being blind and more aware. Black is a oneness with birth. Black is within totality, the oneness of all. Black is the expansion of consciousness in all directions.”

According to the artist, the increasing exploration of outer space inspired his interest in blackness. In fact, his gestural paintings of black circles can suggest black holes, supernovas, or interstellar orbits as well as broader ideas about energy, mass, gravity, and speed. As a supporter of the Civil Rights movement and collaborator with like-minded African American musicians and poets, Tambellini also addressed the racial dimensions of blackness: he argued that the Black Power movement would help “destroy the old notion of western man,” leading to a new utopia of racial equality and democratic culture.

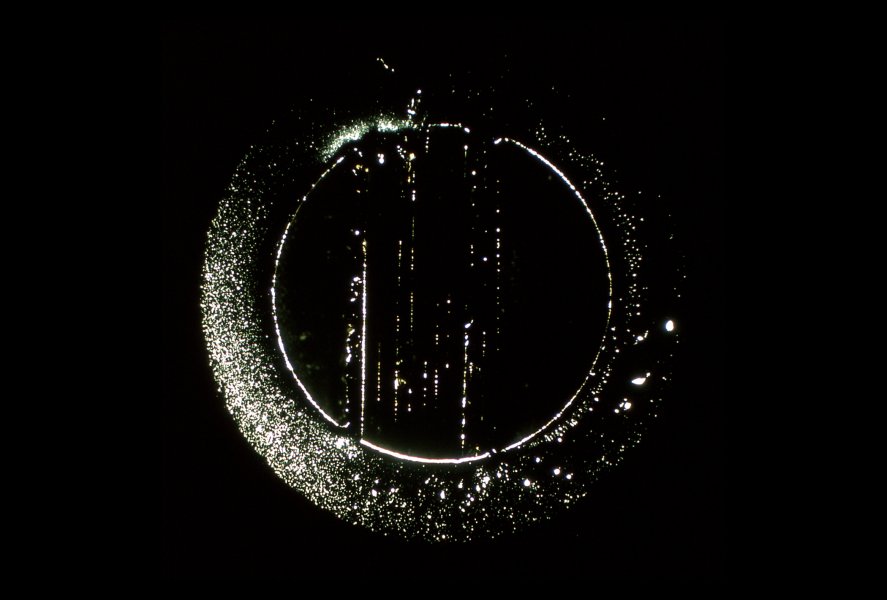

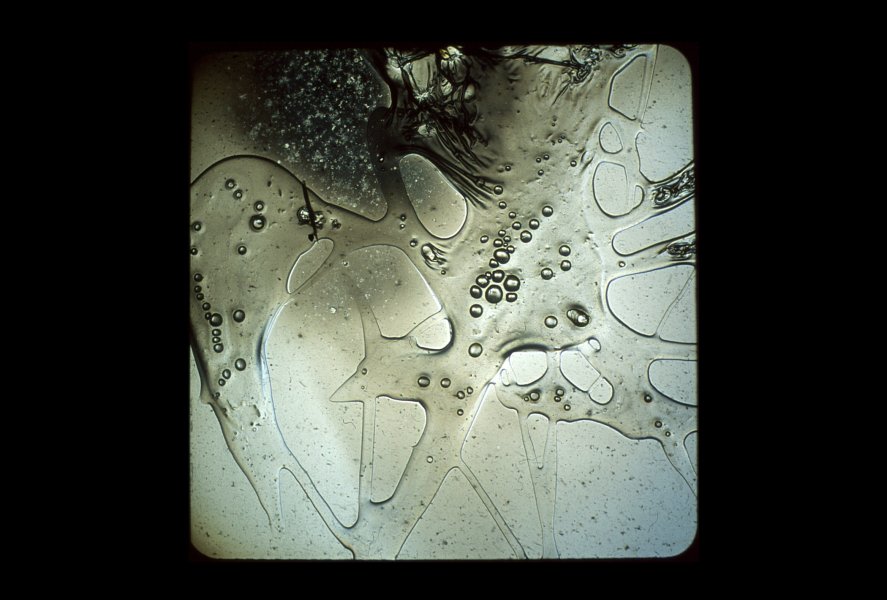

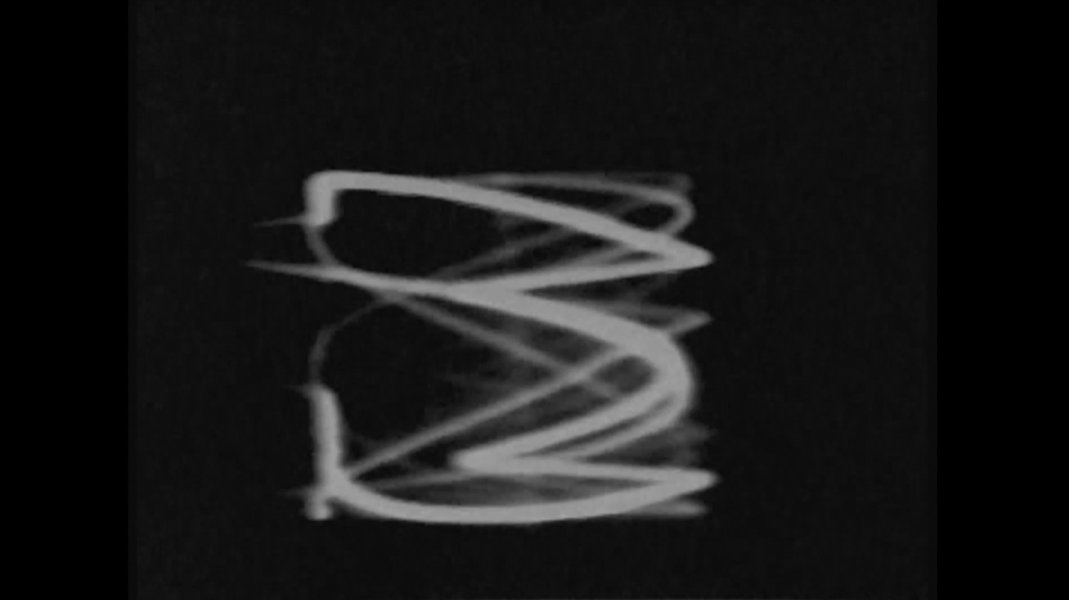

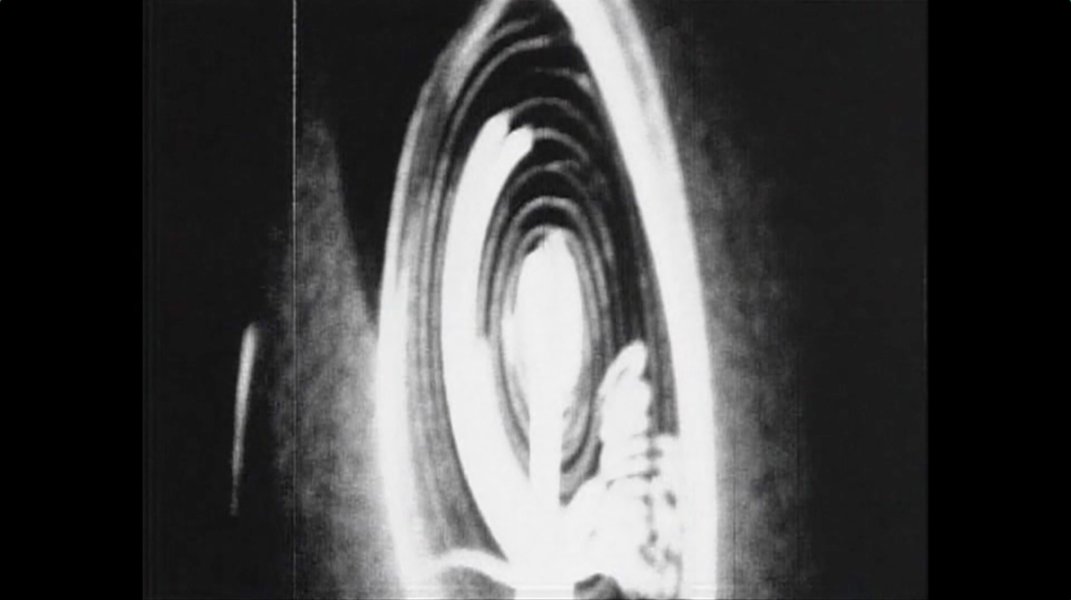

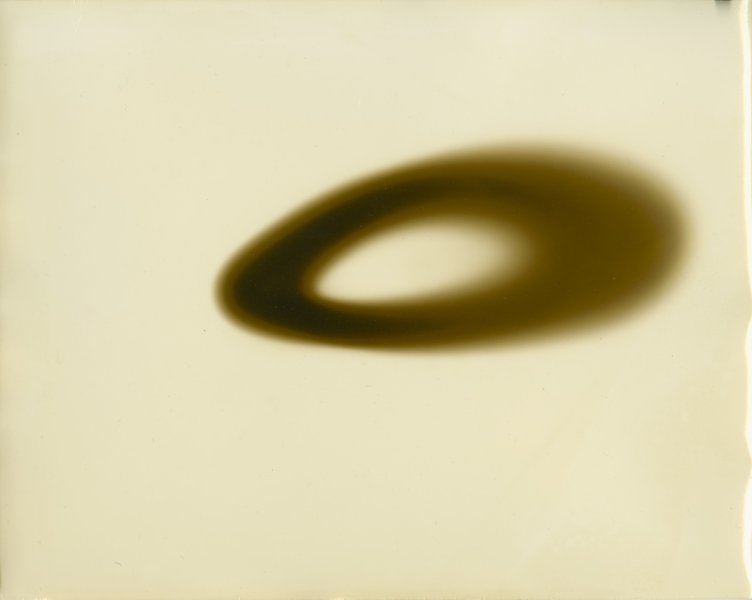

While continuing to paint, sculpt, and promote socially conscious art, Tambellini began experimenting with light-based media technologies, which allowed him to use darkness itself as a material. Around 1963, he scratched, burnt, and painted black spirals and other abstract forms on discarded 35mm slides, calling the projected images “lumagrams.” In the following years, he continued to use similar compositions in experimental films made with hand-painted or appropriated footage as well as “electromedia” performances that combined music, dance, and spoken poetry with slide and film projections and live and recorded video.

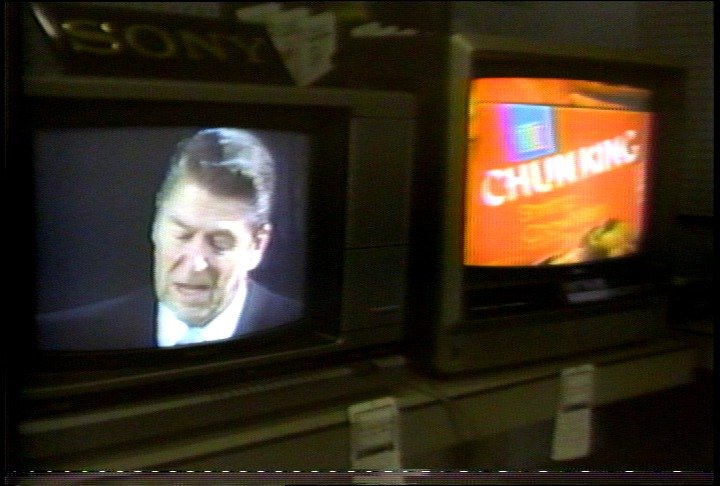

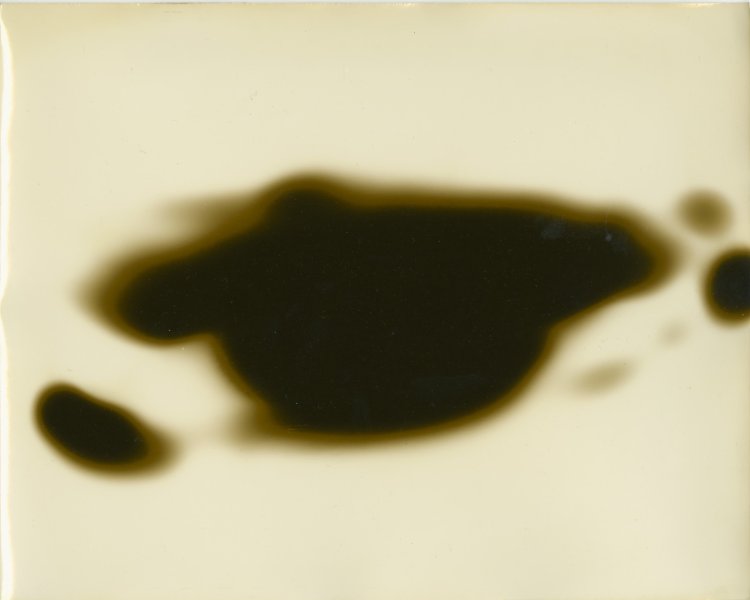

Later in the 1960s, Tambellini coproduced one of the first works of broadcasted video art, Black Gate Cologne. He also contributed to the anthology of new video artworks “The Medium is the Medium,” produced by a Boston television station in 1969. In addition to his innovative work with broadcast television, Tambellini also created some of the first video art sculptures and single-channel tapes as well as a unique body of “videograms,” which he made by directly exposing photosensitive paper to television screens. Examples of these works were included in two key early exhibitions of video art, TV as a Creative Medium (1969) and Vision and Television (1970).

In 1976, Tambellini was invited to join the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Over the next eight years, he developed projects using videoconferencing systems, satellite links, closed-circuit televisions, and other new telecommunication technologies. More recently, he has devoted himself to writing political poetry and the activities of The Aldo Tambellini Foundation. His work has been the subject of retrospectives at the Chelsea Art Museum in New York (2011) and ZKM in Karlsruhe, Germany (2017), and his electromedia performances have been restaged at Performa in New York (2009), Tate Modern in London (2012), and elsewhere. His films have been screened at museums including The Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and are part of the collection of the Harvard Film Archives.

In 2019, the Albright-Knox became the first American museum to hold his work, thanks to a gift by the Aldo Tambellini Foundation that includes examples of his paintings, lumagrams, videos, and videograms. These new acquisitions join other notable works in the collection by Tambellini’s peers, including his collaborator and MIT colleague Otto Piene, midcentury monochrome painters like Clyfford Still, experimental filmmakers like Paul Sharits, and early video artists like Nam June Paik. The gift also represents a homecoming of sorts for Tambellini, who taught at Buffalo’s Rosary Hill College—now Daemen College—for a year in the late 1950s.