How do you become an icon? Marisol was able to navigate popular culture with more than the usual canniness. Not only an iconic artist within the Pop art movement, she turned media to her advantage and circumvented the traps set out for women artists at the time. But how do you influence people’s perceptions of you? How do you use presentation to tell a story? Costume professional Cassie Elsaesser takes us through the making of an icon from the outside in.

How can fashion and clothing choices be used to tell a story?

In costume design, the first step is concept development and putting together mood boards. We think about each piece the character wears and what that says about them. Questions like: Why would this character reach for this sweater? Would this jacket that they are wearing look new, or would it be something they have had and worn in for a while? Often, the answers come from interpreting the situations laid out in the script: What is this character going through? What is going on inside their head? That helps determine what gets the character to reach for each article of clothing.

A key part of designing is collaborating with the director to help relay their vision of the story through clothing. If a director tells wardrobe, “We want him in a suit,” that could mean so many things, but knowing the fuller picture of a character leads our decision making. Instead of thinking “suit” we think “Does this character comes from means? How old are they? What is their intention?” Let’s say this character is young and comes from means—for example, he’s trying to impress the people in the room and he’s trying to relay a position of power—that changes the vision from a suit to a much more specific suit. This narrows it down so much. We would see someone in a well-tailored suit that they spent a bit extra on. They are buttoned up a bit more, shoes are a little newer, etc.

Personal style operates much the same way, except we are trying to visually depict the story about ourselves we portray to others. We dress to enhance what we want others to notice, or not notice, about us. Our clothing offers a method for others to infer something deeper about who we are, or who we want them to think we are.

What do Marisol’s fashion choices tell us about how she presented herself and the story she was telling about who she was?

To be fashionable is to be good at dressing to represent something you want others to infer about you. To me, there is no question Marisol understood this and was herself very fashionable.

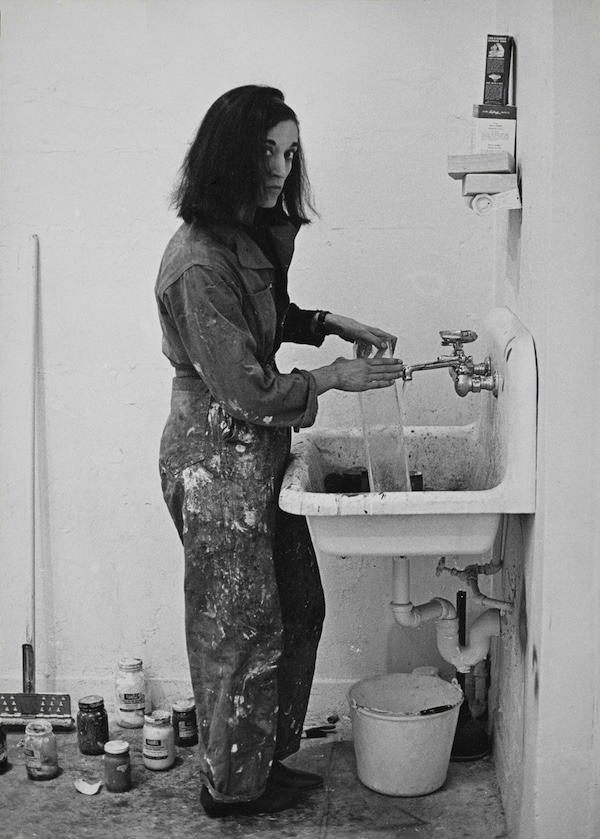

She was very thoughtful about her appearance and understood how her appearance dictated how she was perceived. There was an obvious captivation with her aesthetically that went beyond the works she made, as can be seen in the photographs of her in magazines. I think Marisol leaned into that, especially early in her career. She seems to have chosen each outfit piece carefully and re-wore the pieces she felt worked well a lot (common in the days before faster fashion production). She’s rarely smiling in photos, extending her outfit choices to her expression, but in seeing all her effort I think she enjoyed creating the mystique of her persona. She reflects a lot of culture in New York City—at that time and now. It is a city where people dress to be seen and to impersonate what they are working on becoming. Marisol seemed to be in on it, her clothing choices mirror the scene she surrounded herself with but also were uniquely her own. She always looks at home no matter the situation: a black dress and fur in what looks like an uptown party, a hint of French creative in her studio wear, or sophisticated socialite around Warhol and his associates.

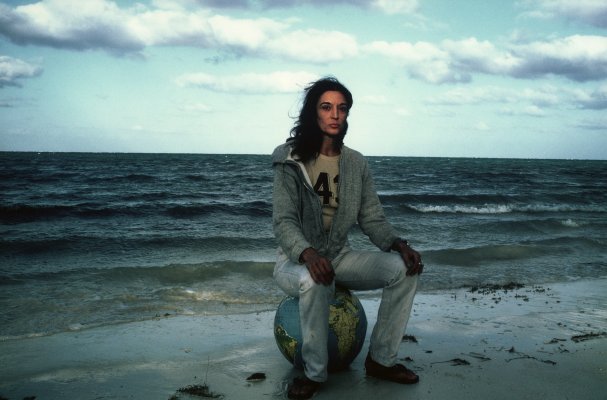

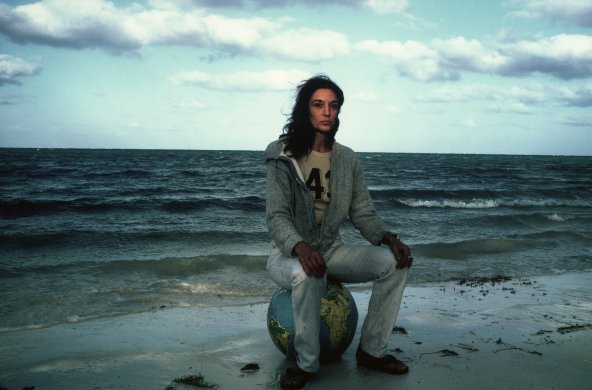

What is particularly interesting to me is the Harry Mattison photo of her in a zip-up hoodie and jeans on the beach. There is a certain cool factor about her in that image and exemplifies the power she brought to what she was wearing with her body language. Overall, I think she presented herself very seriously because more than anything she wanted her work to be taken seriously, and she knew that as a woman her work was tied so much to her image.

What does it tell you that Halston would have made clothes for Marisol? What do the designs tell us about how Halston perceived Marisol?

I think Halston was a person that tied himself to “It” girls of the time, and his view of Marisol might have been just that. He was inspired by these chic women. Think: Liza Minelli, Bianca Jagger, Elizabeth Taylor, all known for wearing a plethora of his designs. He was a designer that loved to design for his vision of the modern woman; long slender silhouettes in lush silks and velvets accentuate the Halston woman, an aesthetic that extended from the larger-than-life parties and clubs Halston was known to frequent. His dresses and jumpsuits became a personification of the elegant women, youthful and provocative while maintaining a level of classic sophistication. I think their relationship makes sense to me, as creatives, as visionaries, and as friends. I can only speculate what they saw in each other, but they clearly both understood the process of personifying fashion. I can imagine the mutual respect they would have for one another’s craft and Marisol’s delight in Halston feeling she would represent his work well.

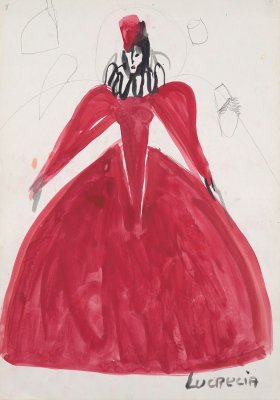

How do you see Marisol approaching the task of costume design? What do her designs say? What story is she telling?

In images of her at work in her studio next to images of her backstage with the costumes for a performance, we see the same look, the same intent focus on creating. I think here we see Marisol’s interest in fashion take a turn and become less about how she presents herself and more an extension of her art. Much like her sculptures, she is creating meaning in a new medium, one that will be worn and move. As a costume designer, my role is to help bring a character from a script into a fully realized human on screen. A film and an audience have an arrangement of sorts, the film takes the viewer into its world and the audience suspends its disbelief to take in the story. A scene can lose all credibility to the audience if they are removed from that state because the wrong costume wears wrong on the character. We, as audience, cannot help but think about what doesn’t seem right, almost an uncanny valley effect, and those moments remove us from the story of the film. I would expect that Marisol understood that arrangement, maybe even embraced the stakes of it, when designing costumes for the stage. In those moments her work is not stationary in a gallery left for interpretation but instead a crucial component to the magic movement of storytelling.

What are the differences in the ways Marisol presents herself as a public figure vs. an artist in her studio? (Maybe the studio uniform is as much a self-conscious choice as her social attire.)

As much as I love fashion as an expressive medium, I think what strikes a particular chord in me is how people dress in utilitarian moments, i.e., Marisol in her studio. In going through her archives, I was particularly drawn to a pristine work jumpsuit that matched one in a photograph that had been worn down with paint all over it. I love the idea that she possibly thought so much about her studio uniform, that when she wore one jumpsuit out, she would have a new one on hand. The intention behind what she was wearing while creating seemed to me to be just as important as the intention in which she dressed when at an opening or party. While different, they go hand in hand when trying to understand a person more completely from deciphering the intention behind how they presented themselves. With someone who is trying to convey something like Marisol, there’s importance to how she dressed in her own space of creation and the world outside of it.

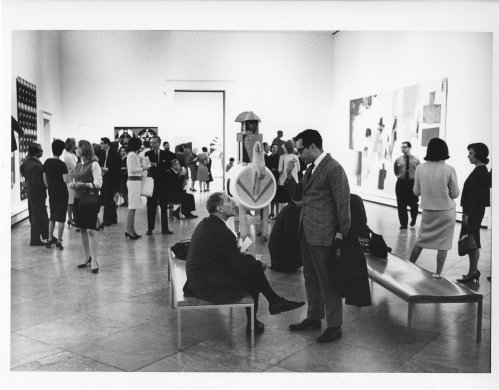

There is something interesting about taking in a survey of Marisol’s work like the retrospective at the Buffalo AKG while thinking about her personal fashion sense. It becomes clear she was acutely attuned to the nuances that status clothing and accessories convey. One of these moments happens clearly in two sculpture works facing one another: the well-dressed guests of the The Party across from the solid almost-secondary colored bodies of the figures in Mi Mama y Yo. Marisol very deliberately features wardrobe in places where it adds to the story she is telling, while in other places she removes its meaning by not incorporating it at all.

Throughout the exhibition Marisol uses casts or images of her own face, sometimes on multiple figures in the same work, which makes me think she saw herself in many of these scenes, and that would extend to the wardrobe. The intention she placed in her personal image and in her artwork are not mutually exclusive. They speak to a person who was thoughtful in all aspects of appearance—whether out on the town, in her studio, or in her artwork.

Cassie Elsaesser (American, born 1985) is a costume designer based between Buffalo and Brooklyn, New York. She began her career working primarily as a stylist for editorial shoots and e-commerce clients before focusing on the character and story development provided by wardrobe in film. When not on a film, Elsaesser works in the commercial sector with a client list that includes Visa, Amazon, I Love New York, and Frito-Lay. She has been part of wardrobe departments on films such as A Quiet Place Part II (2019), Nightmare Alley (2020), Y2K (2023), and the upcoming Materialists (2024) and as the Costume Designer on 31 Candles (2023) and Cutman (2024). When not on set, Elsaesser maintains an active studio practice focused primarily on painting. Follow her work @cassieelsaesser on Instagram.