From the serene and idealized depictions of the Madonna and Child in early Christian iconography to the raw and provocative representations in contemporary works, the portrayal of motherhood throughout art history has undergone a gradual shift—a shift that illuminates societal attitudes towards women and their ever-evolving roles. Nina Grenga, the AKG's Digital Content Manager reflects on these images through the lens of the museum's wide-ranging collection.

The depiction of motherhood in art can be traced back to as early as the third century with (at least in Western art) the first portrayal of the Madonna and Child, also known as the Virgin Mary and baby Jesus, in the catacombs of Priscilla, Rome. [1] More notably, the symbolic pair became a major motif of the Renaissance, with artists often portraying mother and son in scenes like Madonna and Child Glorified, 1553. In this work, we see mother and son surrounded by an aura of light, suspended above the Earth. The Madonna, the most prominent figure in the work, is crowned and garbed in elaborate robes that billow at the crescent moon beneath her feet. Like many other portrayals of the mother, she wears a peaceful expression as she holds her son close to her chest. She is the idealized symbol of motherhood.

Being raised in the Roman Catholic Church, I became acquainted with the various portrayals of the Madonna at a young age. Oil paintings and stained-glass mosaics perpetuated themes of nurturing, protection, learning, and, at times, grief. [2] The Virgin Mary was epitomized as the perfect mother, and as a child, I found myself confused by this narrative because, to me, my mother was perfection. No, she was never surrounded by a glowing aura, and while raising six children, picturesque moments of serenity like those depicted were rare. Yet, while recognizing the artistry in these idealized portrayals, I began to question the representation of women in art and the messages it conveyed.

In Pierre-Auguste Renoir's Mère et Enfant (Mother and Child), 1910, we see a similarly intimate moment between a mother and her child. Renoir was known to portray women in a romantic light, oftentimes focusing on “placid, soft-textured women who possess physical qualities reminiscent of the voluptuous nymphs often depicted in eighteenth-century French Rococo painting.” [3] This idealized body type is evident in the portrayal of the mother in this painting. She is depicted with soft and rounded features, and her tranquil expression complements the inquisitive and innocent gaze of her child. The child is seated on the mother’s lap while her arms encircle them in a tender yet safe embrace. Like the Madonna, the maternal and nurturing presence is integral to the work.

Although a timeless work, Renoir's approach to representing motherhood is traditional and highlights the prevailing domesticity of women’s roles in society. In France, during the creation of this painting, the women's suffrage movement had already gained momentum. This momentum culminated in the ongoing efforts for women's rights at the onset of World War I. [4] Suffragettes fought for independence, equal opportunities, literacy, legal rights, and acknowledgment beyond their roles as mothers, wives, and homemakers. While art doesn't always reflect the political climate of its time, Renoir’s work provides insight into the expectations of motherhood in that era, an image at odds with the women’s suffrage movement of its time.

In 1920, American artist George Wesley Bellows painted Elinor, Jean and Anna. If you have seen this artwork in person, you know how overwhelming it can be at first glance despite its muted color palette. This large-scale portrait depicts the artist’s mother, Anna, aunt Elinor, and young daughter Jean. While the two older women are dressed in black and blend into the shadows of the dimly lit space, Jean is illuminated in a white dress at the center of the work, a large book in her lap. In a barely perceptible motion, the aunt extends her hand, palm up, towards the girl.

This artwork has always felt bittersweet to me for several reasons. In the physical arrangement of the subjects, the similarities between the faces of grandmother and granddaughter, the extension of Elinor’s hand, and the book held by Jean, it feels like an introduction and “passage of wisdom” to the newest generation. [5] There is a sense of hope for what is to come and a quiet confidence in the women surrounding the young girl. To witness the generation of women who came before the daughter is a powerful scene to behold. However, their placement in the shadows and as almost part of the background adds a somberness to the work. While I can’t speak to the experiences of the women of this era, I can speak to my own and those of women I know. Society has a way of placing subliminal expiration dates on the value of women. It prioritizes youth over experience and suggests that our prime only lasts a decade or two. After that time has passed, like Elinor and Anna, we’re expected to fade from the forefront.

Arguably, one of the most iconic works in the Buffalo AKG’s collection is Marisol’s Baby Girl, 1963. Sculpted from wood and mixed media, this six-foot-tall work depicts an overwhelming infant girl. The magnitude of her size contrasts with her ruffles, bows, and Gerber baby-esque painted face. Marisol inserts herself in the work at small scale in the child's lap. The juxtaposition between the two figures represents the daunting nature and expectations of motherhood. In her essay for Marisol: A Retrospective, Delia Solomons points out that Baby Girl (along with her paired Baby Boy, 1962–63) could be the artist’s “exasperated, humorous rebuttal to journalists pestering her about getting married and ‘making babies’. . .” [6]

The anxieties presented in this work remind me of those presented in Sylvia Plath’s poetry about motherhood, specifically Morning Song, written in 1961:

Love set you going like a fat gold watch.

The midwife slapped your footsoles, and your bald cry

Took its place among the elements.

Our voices echo, magnifying your arrival. New statue.

In a drafty museum, your nakedness

Shadows our safety. We stand round blankly as walls.

I’m no more your mother

Than the cloud that distills a mirror to reflect its own slow

Effacement at the wind’s hand.

All night your moth-breath

Flickers among the flat pink roses. I wake to listen:

A far sea moves in my ear.

One cry, and I stumble from bed, cow-heavy and floral

In my Victorian nightgown.

Your mouth opens clean as a cat’s. The window square

Whitens and swallows its dull stars. And now you try

Your handful of notes;

The clear vowels rise like balloons. [7]

Plath depicts a woman's first moments of motherhood, including the birth of her child and waking up in the middle of the night to feed them, and the apprehension she feels in response to this new reality. Essentially, the poem illustrates the disconnection between a new mother and her infant. The speaker refers to the child as objects like "a new statue" in a "drafty museum" instead of directly addressing them as a baby. Throughout the poem, the mother grapples with her new role, the discomfort within her body and of her sexuality, and bonding with her child. The enormity of the concept of motherhood in this writing mirrors both the literal and figurative enormity of the Baby Girl. I found it interesting how both Marisol, who never became a mother, and Plath, who had two children, shared the same anxieties about maternity. While the prospect of motherhood is not a current priority in my life, I find solace in the voices of women—those who have become mothers and those who have not—who bravely display these shared fears and vulnerabilities.

An artist who has continuously discussed topics surrounding motherhood and domesticity throughout her work is Janine Antoni (Bahamian, born 1964). [8] Her works Umbilical, 2000, and One Another, 2008, explore the nature of mothers feeding their children and how life propels out from them. In Umbilical, Antoni connects an impression of her mouth to an impression of part of her mother’s hand by a silver spoon from her family’s collection. The artist explains, “I thought it was curious that I had fed from her [my mother’s] body, that maybe she had actually fed me from this particular spoon, and now she wanted to turn around to give me an object for feeding others. It’s an object loaded with ideas of domesticity and culture.” [9] Eight years after that work, One Another catches a surprising-yet-tender moment between Antoni and her daughter, which connects with Umbilical. Her daughter attempts to feed her mother through her navel, subliminally mimicking the prenatal stage she shared with Antoni while in the womb. “As One Another shows a daughter’s intimate gesture that returns the artist to her ‘fetal memory,’ so Umbilical embodies the artist’s memory of the nurturing exchange between her and her own mother.” [10]

There is a celebration of the relationship between mother and child in these works by recognizing the rawness of our needs as living beings and the intimacy that accompanies such. Antoni challenges the stereotypical depictions of motherhood by embracing the humanity of it all. As I was reading Antoni’s words about these works, I was reminded of an interview with Toni Morrison where she discusses the liberation she found in becoming a mother through the candid needs of her children: [11]

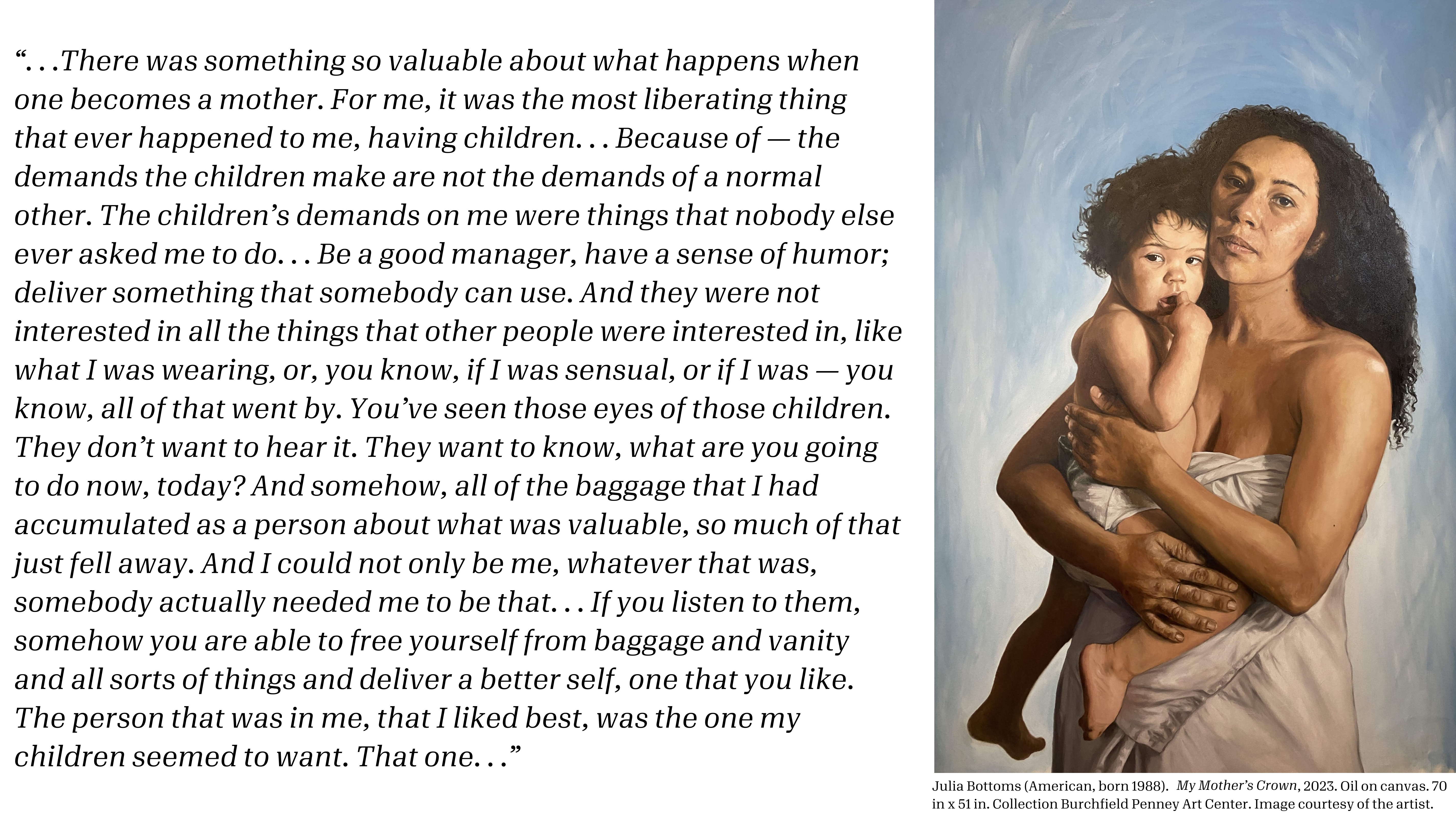

Local artist Julia Bottoms (American, born 1988) is no stranger to the Buffalo AKG, having participated in the museum’s Public Art Initiative on numerous occasions and, more recently, exhibiting her work in the exhibition Before and After Again. Her sheer talent and attention to detail have never ceased to amaze me, especially in her self-portrait, My Mother’s Crown, 2023. [12] In this work, Bottoms is dressed in a white towel, holding her diapered child close to her, offset by a serene blue background. My Mother’s Crown is reminiscent of portraiture in early art history while celebrating the reality of the modern mother. We see the etherealness portrayed in works depicting the Madonna and Renoir’s Mère et Enfant (Mother and Child), but without embellishments. We see a child at ease in the safety of their mother’s arms, skin against skin. We see a mother—the wrinkles in her hands, the texture of her skin, her hair loose down her back—in all her natural beauty.

When it comes to depicting motherhood in various artworks throughout history, we should celebrate the diverse interpretations and techniques. However, this celebration should not overlook the reality of motherhood. I hold the women in my life in the highest regard, and it has always been important to me that they receive the recognition they deserve, including those who have maternal roles. In the beauty of the Mère et Enfant (Mother and Child) and the vulnerability and strength in Marisol's and Janine Antoni's works, I find echoes of the women who have played significant roles in my life. I see my mother, my sister, my grandmothers, aunts, and cousins. I see my friends, my academic mentors, and my colleagues. I celebrate the artistry and I celebrate the women who have shaped me into who I am.

Footnotes

[1] https://www.ilariamarsilirometours.com/blog/the-first-image-of-the-madonna

Higgins, Sabrina. (2012). Divine Mothers: The Influence of Isis on the Virgin Mary in Egyptian Lactans-Iconography. Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies. 3-4. 71-90.

[3] https://buffaloakg.org/artworks/19406-m%C3%A8re-et-enfant-mother-and-child

[4] https://guides.loc.gov/feminism-french-women-history/19th-century

[5] https://buffaloakg.org/artworks/192332-elinor-jean-and-anna

[6] Brodbeck, Anna Katherine; Brodsky, Estrellita; Da Corte, Alex; Desmarais, Mary-Dailey; Hong; Hose, Jason; Jessica S.; Solomons, Delia; Vázquez, Julia. Marisol: A Retrospective, 67-87. Buffalo AKG Art Museum in Buffalo, New York, and New York, New York in association with DelMonico Books/DAP, 2023.

[7] Plath, Sylvia. The Collected Poems, 156–57. Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2008.

[8] Dreishpoon, Douglas; Grachos, Louis; Pagel, David; Pesanti, Heather. Decade: Contemporary Collecting 2002-2012, 244. Albright-Knox Art Gallery Buffalo, New York. 2012.

[9] https://buffaloakg.org/artworks/20035-umbilical

[10] https://buffaloakg.org/artworks/p20104-one-another

[11] https://billmoyers.com/content/toni-morrison-part-1/

[12] https://burchfieldpenney.org/art-and-artists/artwork/object:my-mothers-crown/