Clyfford Still was famously unimpressed by art critics’ efforts to describe and analyze his paintings, which he believed should stand on its own as a collective body of self-expressive work. And yet here I am, though not an art critic, trying to say something—but also not to say anything—about that work.

I first encountered Still’s paintings on a cold Denver evening in December of 2015. Two old friends were in town for the holidays, and we agreed to meet up at the Clyfford Still Museum. As I drove downtown I listened to a Radiolab episode about Dr. Anne Adams, who in the mid 1980s left her career as a cell biologist to paint full-time. After making dozens of paintings of strawberries and houses, in 1994 Dr. Adams painted “Unraveling Bolero,” a large two-panel representation of all 340 bars of Maurice Ravel’s Bolero: a playful but menacing little tune repeated 169 times, growing louder with each iteration as though punching its way out of the orchestra and finally breaking free with an inarticulate yell.

There’s no perfect way to describe the precision with which “Unraveling Bolero” renders abstract music into an only slightly-less abstract visual form. At first glance “Unraveling Bolero” seems to depict a series of brightly colored rowhouses shrinking into the distance behind slim profiles of skyscrapers at dawn. Each color, shape, and symbol in the painting refer to a specific note in the Bolero, but no matter how many times I listen to the music while staring at the painting, I still can’t decode it. It teases a desire for referentiality which I often fancy I’ve outgrown.

Dr. Adams—and Ravel before her—were both diagnosed with progressive aphasia—frontotemporal dementia marked by compulsive repetition and the degeneration of language as the frontal cortex atrophies (Seeley). As Adams continued to paint through the 1990s, her work grew increasingly complex. In 1998 Adams painted pi (π). In 2000 she painted kaleidoscopic mandalas of invertebrates—starfish and octopi and earthworms. As language fails, the visual mind grows increasingly active. The instinct to repeat goes unchecked by language and patients who express themselves through art or music often take an idea and repeat “again and again and again” (Abumrad). One hundred sixty-nine repetitions of the same theme.

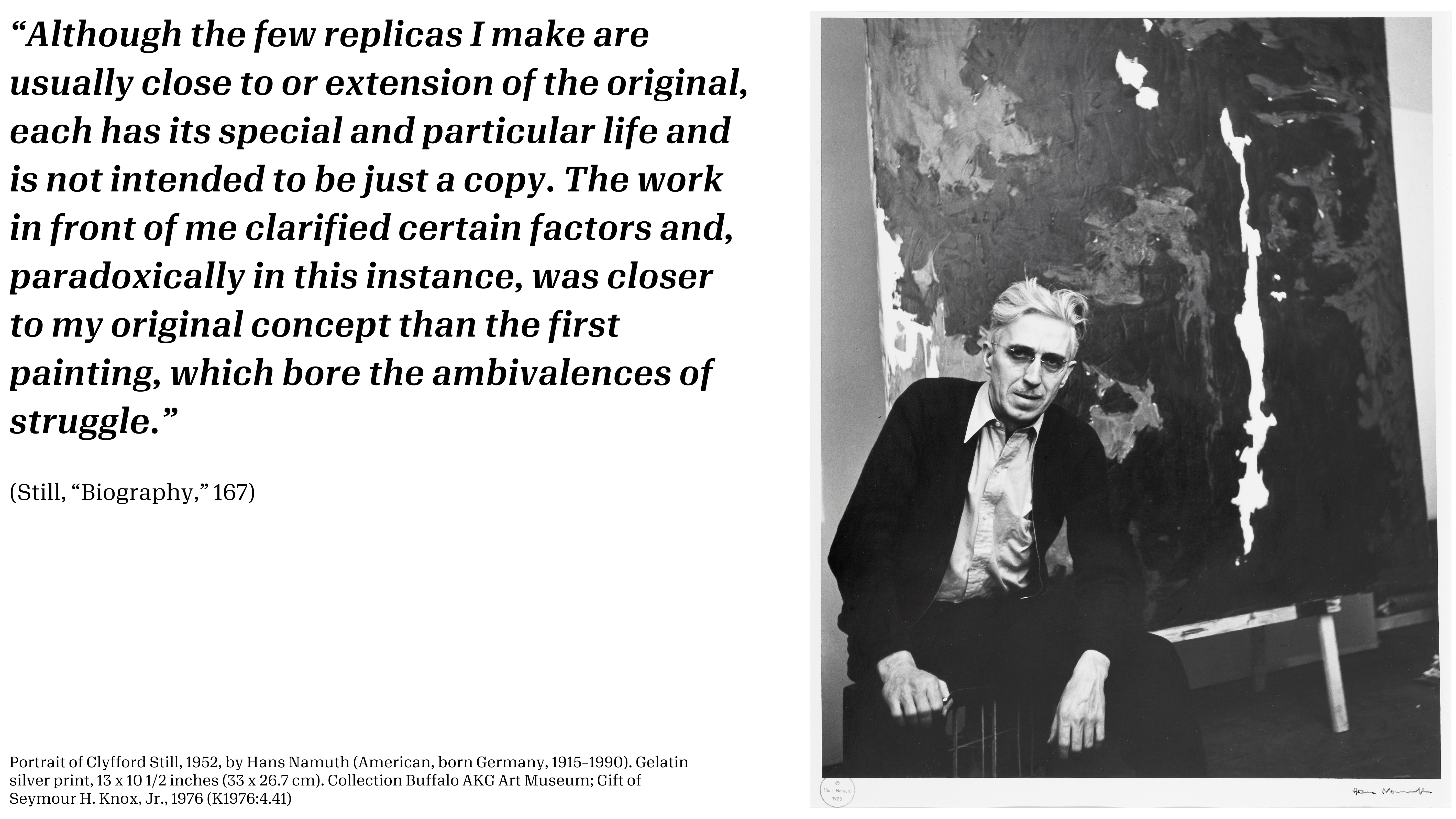

None of this had anything to do with Clyfford Still until I walked into the museum to discover the current exhibition was on Still’s “Replicas.” With Bolero still looping in my ear, we set to studying sixteen sets of nearly-identical paintings, displayed side-by-side. These paintings, though, were not identical copies, but revisions bearing both subtle and sometimes dramatic shifts in size and color. Jagged bands of yellow and orange and black shift just so between three nearly-but-not-at-all identical canvases. Shocks of blue creep into the edges—cobalt disruptions to the black, orange, and yellow palette that seemed to harmonize through an abstract geometry. And it is these disruptions that most captivate me, not because they bring the repetitions into starker relief—but because they do just the opposite. Each shock of blue, each little flame of bright orange bursting onto a painting forces my eyes to seek it out in the others.

I found my eyes following the horizontal narrative of his replicas, looking for disruption, rather than the vertical so often remarked upon in his work. I scanned the horizontal, the diagonal, the meandering, noticing how the lack of horizon in Still’s abstract paintings draws the attention as much to the upward movement of his shapes as to the movement of color. Maybe my personal preference for the horizontal reveals a lack of optimism, or perhaps it’s my constant search for a horizon upon which to ground myself. Like Still, I grew up on the Great Plains, and I’m always catching myself scanning across, rather than upward, as though a flatness will open before me and I’ll find home.

Of course, the delight of these small moments is that they are not repetitions, but in searching for them I begin to see the movement of the paintings, the subtle and not-subtle shifts in shape and color that makes each individual painting a unique event, a study in a palette knife thinking its way through form. Something like gazing at clouds on a day without wind, the simple pleasure of watching their shapes drift and morph and tease the eye’s desire for recognizable forms that never come. There—again—is that impulse toward words.

Still wrote that his abstract paintings were pure expressions of himself, divorced from any representational impulse—that when we encounter a Clyfford Still painting, we are encountering the artist. And the replicas show us that Still’s expression of self was reflective, deliberate, and undergoing a constant process of revision:

What is the original concept of oneself?

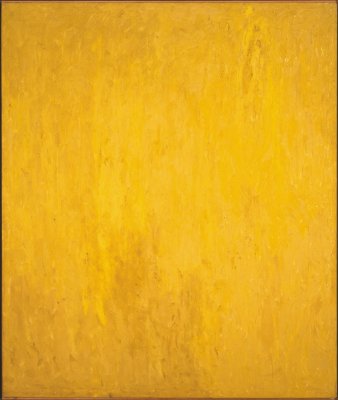

I keep thinking about how the paintings’ tiniest differences provoked such a strong response in me. I remember feeling my heart jump at enormous washes of bright yellow paint (the same way it would jump when I saw Rothko’s 1956 Orange and Yellow a year later in Buffalo).

And I keep thinking about the Bolero, those jagged musical forms growing louder and louder, punching their way out of my car’s lackluster stereo, and here was Clyfford Still, assured in his constant return to his own jaggedness, his lifelines, his fields of color. None of the desperation of the Bolero’s compulsive repetition, but something obsessive nonetheless. One hundred sixty-nine repetitions of the same theme.

Years later, as I study the Still collection at the Buffalo AKG, I’m still curious about the impulse toward repetition—this scale, this technique, this fathomless color are all unmistakably Clyfford Still. Thirty-three fields of color with all their shapes and only faulty language to describe them: lines, flames, patches, bursts. And the horizontal of these canvases continues to captivate me.

November 1953, 1953 beckons you to look up and metaphorize—to follow the blue into the black and try to say something about the shaggy cap of dark red at the top, almost missing the bit of canvas in the lower corner that perfectly balances the composition. Let the eyes travel across.

Or consider September 1955’s ten feet of monochromatic siennas and umbers so modestly but provocatively offset by the strip of ochre on the left of the field, a brightness that dominates this viewer’s attention. The title of the painting likely refers to little more than the date of composition, but one can’t help but think of the gradually shifting colors of approaching autumn, seasons splicing themselves together. Or, to put it less representationally, here is an unfolding relationship between colors.

Perhaps just as exciting, if even more subtle, is November 1950, 1950. Still didn’t want us to draw allusions, but the feeling of looking at this work is similar to gazing over the Great Plains just before winter rolls in—minus, of course, that great horizon. Still was clear: the works were expressions of himself, of feeling deliberately communicated through color. But I can’t help but see that Plain, so often called monotonous by mistake, when it is really so vibrant. There is nothing monotonous about this how this painting’s structure animates its shades of gold.

Those umbers and golds, those plains and seasons, those irrepressible associations. As Still wrote in the catalog for the 1952 “15 Americans” exhibition: “That pigment on canvas has a way of initiating conventional reactions for most people needs no reminder… The observer usually will see what his fears and hopes and learning teach him to see. But if he can escape these demands that hold up a mirror to himself, then perhaps some of the implications of the work may be felt” (Still, “Biography,” 157). Still would eventually stop giving titles to his paintings. Without months and years to contextualize these paintings, would I be able to see them more clearly?

What if there was only language, and no pigment?

Browsing through his earliest work, from the 1920s, on the Clyfford Still Museum’s online archive, the viewer is met by sketches of chickens, deer, and farm equipment—a young artist’s exercises. Except to look at the oil paintings of a woman feeding chickens on the farm or cows milling in the dirt streets of a frontier town reveals a practiced hand and eye, even at the age of 20. It’s easy to forget, looking at Still’s jagged expanses of color and trying to let go of one’s learned reactions that Still was a remarkable figural technician—his turn to abstraction was made with skill and deliberation.

But his eye for the event of color was always there. In browsing through the archive I came across another type of study: a page with a few wisps of cloud over a faint horizon line and some scribbles that could be brush or grasses.

This is not the focus of the sketch, though. The focus is on color, though the only color on the page is the faintest smudge of purple and yellow with the word “fantastic” written beside it in the artist’s tight cursive script:

!["leaf yellow-silver stalk purple-silver silver willow [massed?]-silver- purple silver fantastic" next to an image of a paper with cursive handwriting](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Clyfford%20Still%2C%20PNX-22%2C%20c.%201927.%20Graphite%20and%20pastel%20on%20paper%2C%209%20x%2012%20inches%20%2822.9%20x%2030.5%20cm%29.%20Clyfford%20Still%20Museum%2C%20Denver%2C%20CO.%20httpscollection.clyffordstillmuseum.orgobjectpnx-22.1%20%281%29.jpg)

It’s a color study without color, patches of “cool blue” adjacent to “a dull hazy pink cream fading to grey” and grasses that shift from “tan… spotted with silver” to “dark grey-green” the closer they come to the viewer. Again, rather than scanning up, you must scan across, read around, and conjure the relationship between the pigments.

And with a little imagination, this 100-year-old piece of paper becomes a field of color—light greys, warm greys, a variegation of silvers, translucent green, brown, and crimson—all drawing our eyes toward that fantastic splash of purple and yellow. And although there may be a lady among the grasses and willows, this word-painting is all about the fantastic propulsion of color—the event and experience of color that can never, ever be replicated.