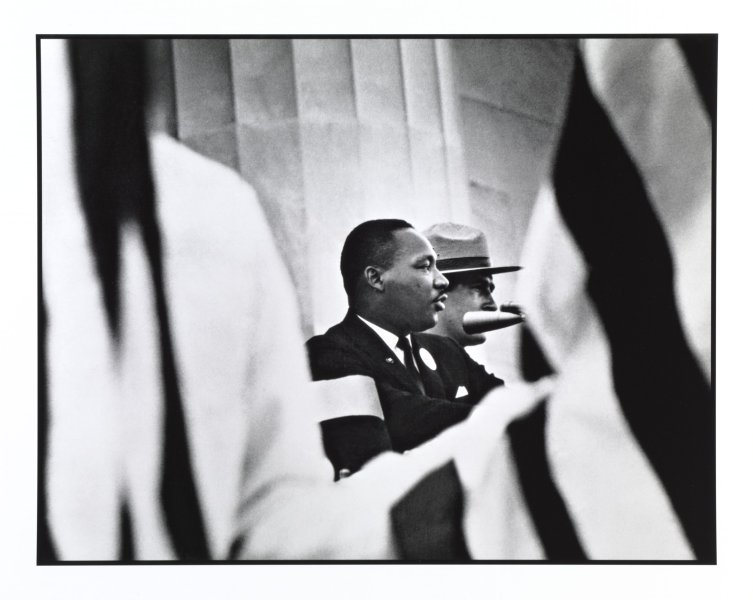

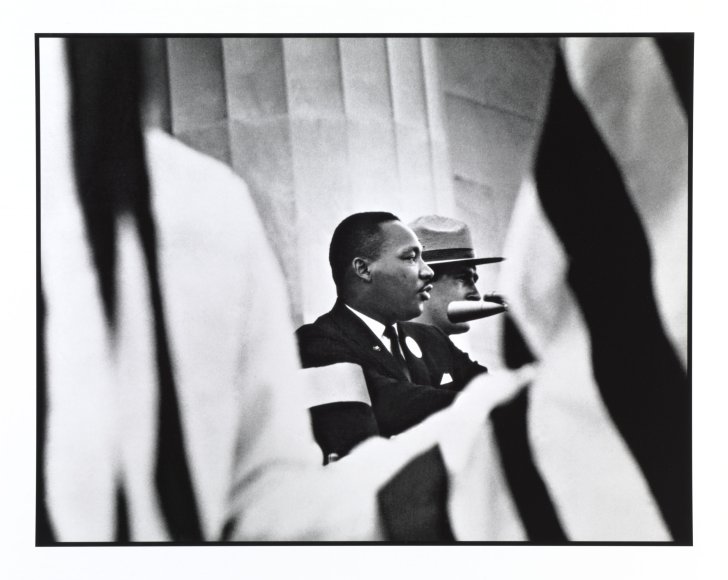

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Gordon Parks (American, 1912–2006). Martin Luther King, Jr., Washington, D.C. from the portfolio I AM YOU, 1963 (published 2017). Selenium-toned gelatin silver print, edition 7/25 from an edition of 25 plus 5 artist's proofs, 16 x 20 inches (40.6 x 50.8 cm). Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; Elisabeth H. Gates Fund, by exchange and Gift of A. Conger Goodyear, by exchange, 2017 (P2017:11.2.3). © Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

One of the most profoundly influential participants in the Civil Rights movement, Martin Luther King, Jr., organized the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott, led the Southern Christian Leadership Council, orchestrated nonviolent protests and marches throughout the United States during the 1950s and 1960s, and delivered a number of speeches that ultimately led to the passing of the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

King recognized that the Voting Rights Act would not entirely solve the country’s systemic problems of racial and social injustice, and he became frustrated with the movement’s lack of progress after 1965. His commitment to nonviolent civil disobedience was questioned by former colleagues and supporters who began to preach the ideology of Black Power and more radical action. But King persisted in his efforts to form a coalition among all races by drawing a relationship between racial and economic inequality. In 1966, King shifted his attention to the north, specifically Chicago, to bring attention to the elaborate network of city laws and ordinances that resulted in the dramatic housing segregation seen there and in other urban centers. At the same time, he became an increasingly vocal critic of the war in Vietnam, stating, “The bombs in Vietnam explode at home; they destroy the hopes and possibilities for a decent America.” Both King’s powerful antiwar message and his efforts to bridge divisions between poor African Americans and whites in order to challenge economic injustice and exploitation drew the ire of important sectors of the federal government, and the F.B.I. subjected King, his family, and his associates to more than two decades of extrajudicial surveillance. In his last speech, on April 3, 1968, King delivered the spiritual message, “I’ve looked over and seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we as a people will get to the promised land.”