By Dr. Barbara Seals Nevergold

Dr. Barbara Seals Nevergold is an educator, historian, and community and political activist. She began her career as a French teacher in the Buffalo Public Schools, where she also worked as guidance counselor. Drs. Seals Nevergold and Peggy Brooks-Bertram founded the Uncrowned Queens Institute in 1999 to promote the collection, preservation, and dissemination of the individual histories of women, women's organizations, and women's collective history; and to teach and educate women on the use of technology to preserve and disseminate their histories. We asked her what role art can play to combat racism. This was her response.

Beginning in the late 1940s and continuing for almost fifty years, my father, Reverend W. B. Seals, was one of the most recognized photographers in Buffalo’s African American community. Photography was one of three avocations in addition to his day job at the Chevy plant in Tonawanda. He was also a Baptist minister and a musician. He took up photography after our move to Buffalo in 1947, quickly moving from a hobby to a side-line business, which he named Seals Ebony Studio.

My father was born in 1910, in the state of Louisiana, under the constraints and de-humanization of the Jim Crow legal and social structure. I don’t know if he would have considered his work as a photographer a form of artistic expression, or if he’d see himself as a social documentarian, or a community historian. But he was an ultimate professional, who worked tirelessly to perfect and update his skills. He actively endeavored to learn new techniques to produce unique, beautiful black-and-white, sepia, and color photos. He was a “jack of all trades,” and early on he devised gadgets to improve lighting and filters to create special effects.

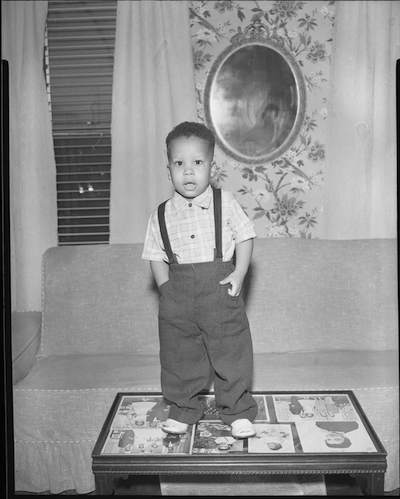

He often used members of his family as models so that he could practice improving the composition and placement of his subjects (a side benefit for us is that we have many family photos). Before color photos were affordable, he used oil-based paints to meticulously hand-paint “colorized” versions of his work. He spent countless hours at his desk with a paint palette, tubes of oils, Q-tips, and cotton swabs, and painstakingly detailed eyes, hair, cheeks, or jewelry with just the right color and shading. For many years he developed and printed the pictures he took, maintaining the negatives and the precious images they contain.

He devised a unique way to advertise. He built the “picture box”, which became a neighborhood fixture in the Fruitbelt, to showcase his work. As a businessman, he kept records that identified the names and contact information of customers and the dates of the photo shoots. The end result of his work is a decades-old collection of stunning black-and-white and color photos that record generations of African American community members and preserved images not frequently seen by members of the broader community.

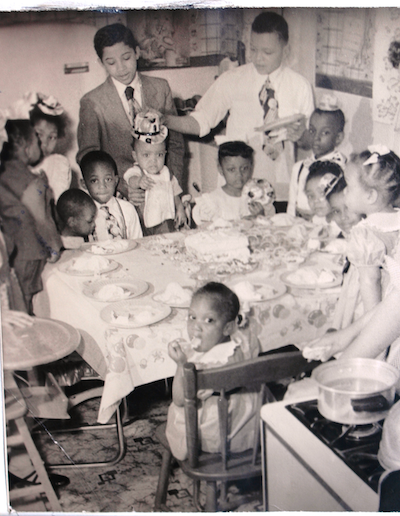

These early photos, especially, feature African Americans engaged in activities, recording memories of people that reflect their humanity and offer glimpses of shared life experiences that are universal: children celebrating birthdays…

Jubilant parades featuring majorettes and marching bands, being cheered on by excited onlookers…

Brides and grooms, exchanging vows, cutting the wedding cake, and being feted by family and friends...

There are pictures of the community’s infrastructure: church choirs and Masonic groups, and examples of some of the community’s organizations.

There are photos that depict the mundane activities, we all engage in: a child riding her tricycle… a group of kids posing outside for a picnic photo or with their favorite toys.

And then there are the photos that invite us into the homes of Black people: the grandmother seated at the dining room table… a woman at a piano or seated on the couch in her living room surrounded by family memorabilia.

Each one offers a remarkable view into the home of an ordinary African American resident. Each offers an opportunity to challenge stereotypes, identify commonalities, defuse the misunderstanding of “the other,” and envision the hopes, dreams, and aspirations of those in the photos. All of these serve to show how we are more alike than not.

My purpose for writing this piece is to suggest that if the old adage, “a picture is worth a thousand words” is true, then maybe we can extrapolate that idea—one picture can start a thousand conversations, contribute to racial understanding, and help reduce the barriers that separate us.

My family is lucky to have many examples of the photographic work of our father, in which we see his artistry. Through Seals Ebony Studio, he was called on by myriad groups and individuals to document the history of several generations of African Americans in the Western New York area, from births to deaths, to marriages and other celebrations, to changes in the life of a community over time. As a minister, he might sum up what I’m trying to say with the quote, “Let his works speak for him.”

Learn more about Buffalo's history and the work that Dr. Nevergold does at Uncrowned Community Builders.