In early 1971, Kay Brown, Dindga McCannon, and Faith Ringgold gathered a group of black women at McCannon’s Brooklyn home to discuss their common frustrations in trying to build their careers as artists. Not only did they find that juggling their creative ambitions with their roles as mothers and working heads of households left little time to make and promote their art, but they also felt excluded from the largely white downtown art world as well as from the male-dominated black art world.

Out of this initial gathering came one of the first exhibitions of professional black women artists: “Where We At”—Black Women Artists, 1971. Adopting the show’s title as its name, the collective began meeting at members’ homes and studios, building support systems for making their work while assisting each other with childcare and other domestic labor. Where We At recognized the power of collectivity—empowering black women by creating a network to help them attain their professional goals as artists.

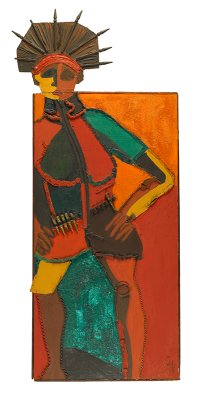

Dindga McCannon, one of the co-founders of Where We At, wrote about her inspiration for making Revolutionary Sister:

In the ’60s and ’70s we didn’t have many women warriors (that we were aware of) so I created my own. Her headpiece is made from recycled mini flagpoles. The shape was inspired by my thoughts on the Statue of Liberty; she represents freedom for so many but what about us (African Americans)? My warrior is made from pieces from the hardware store—another place women were not welcomed back then. My thoughts were my warrior is hard as nails. I used a lot of the liberation colors: red—for the blood we shed; green—for the Motherland—Africa; and black—for the people. The bullet belt validates her warrior status. She doesn’t need a gun; the power of change exists within her. The belt was mine. In the early 70s bullet belts were a fashion statement, I think inspired by the blaxploitation movies of the time. I couldn’t afford the metal belts, probably purchased at Army Navy surplus stores, so I made do with a plastic one.