Ronny Quevedo

Ecuadorian, born 1981

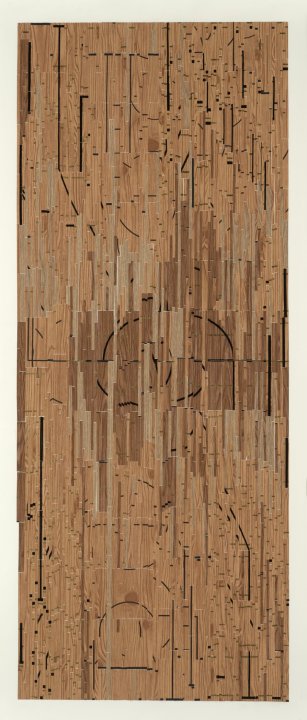

no halftime (ode to my father), 2020

Artwork Details

Materials

paint, screenprint and gold leaf on contact paper

Measurements

sheet: 66 1/2 x 28 inches (168.91 x 71.12 cm)

Collection Buffalo AKG Art Museum

Credit

Gift of the Winfield Foundation, by exchange, and Jamie and Emmett Watson, 2021

Accession ID

2021:4

Ronny Quevedo’s mother is a seamstress and dressmaker and his father played soccer professionally in Ecuador. Though drawn from personal history, Quevedo’s work conveys stories that relate to the experience of many immigrants. When the family moved to the United States, his father worked as a referee and joined a local amateur soccer league largely composed of migrants from Central and South America and the Caribbean. Despite arriving from different places, the players shared a language and the experience of assimilating to life in the United States. These weekly gatherings came to carry a ritualistic significance for Quevedo. The teams often played indoors in high school gymnasiums, revealing, for the artist, how such sites can be repurposed and reinvented.

Quevedo’s no halftime (ode to my father) is a composition on paper that he created as part of the development of the large-scale installation the killing floor (el piso de matanza) for the Albright-Knox exhibition Comunidades Visibles: The Materiality of Migration. Wood contact paper, cut to mimic the long and narrow floorboards of a gymnasium, is punctuated with gold leaf and black paint. The marked lines of a basketball court are therefore rearranged, destabilizing the visual vocabulary of any individual sport. “By altering the function of lines on the floor,” Quevedo explains, the players “created their own rules within the existing order of things.” The artist is interested in what he calls the “freedom of function,” separating materials from their usual uses in order to connect with his experiences of migration and assimilation.