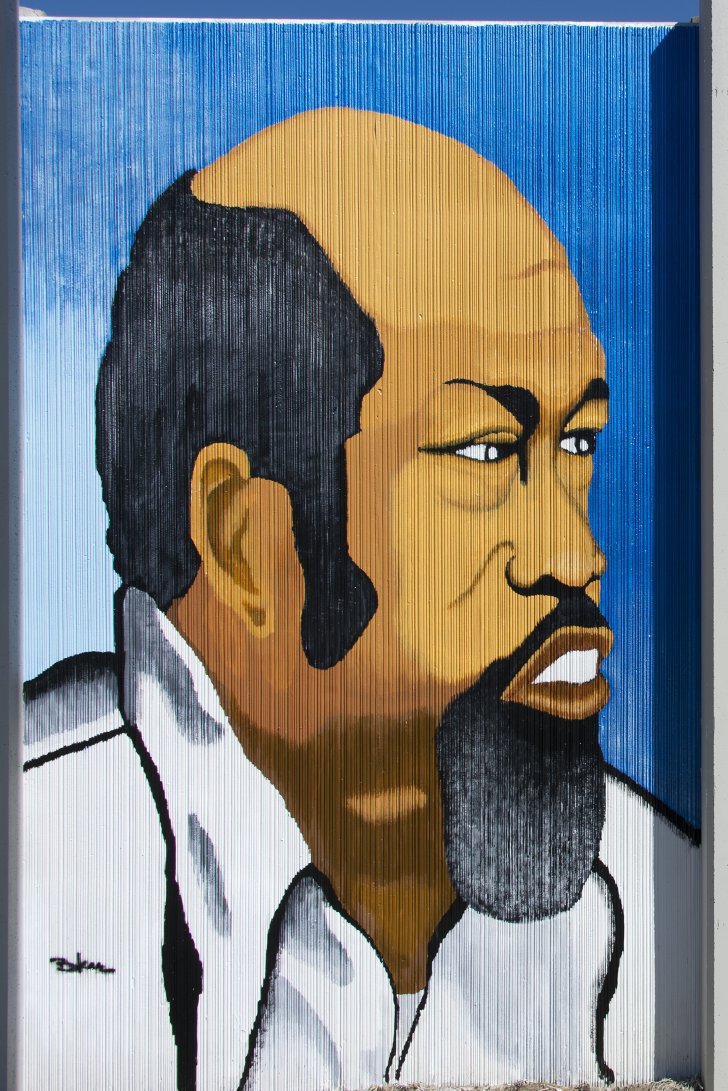

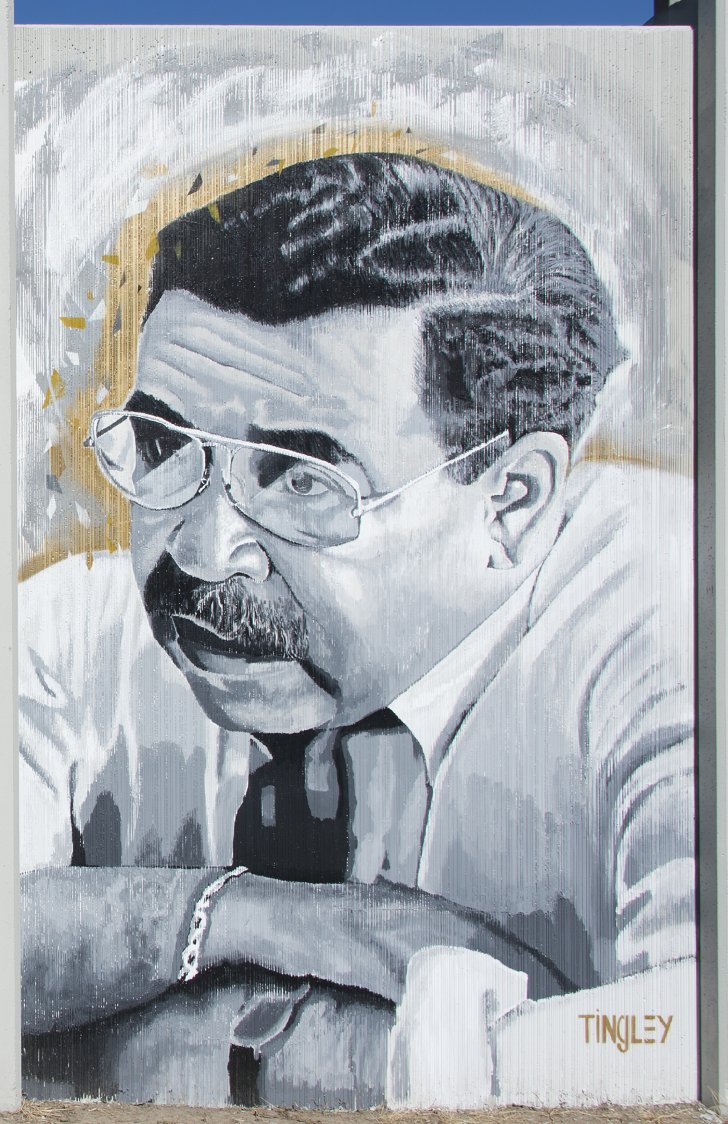

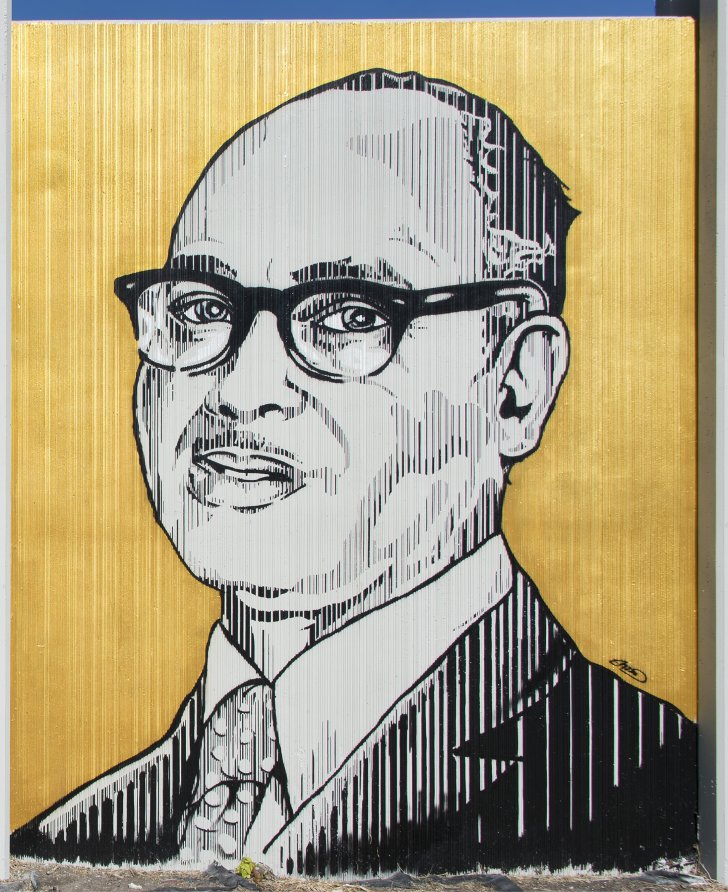

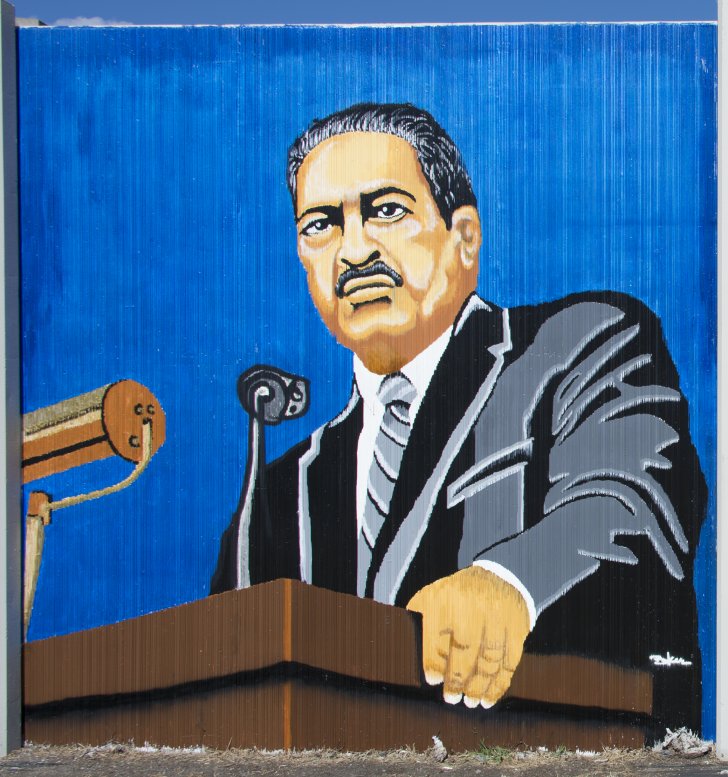

1941–1998

Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Toure)

Painted by Chuck Tingley

At once influential and divisive, Stokely Carmichael is best known for popularizing “Black Power” as both a powerful slogan and a philosophy of self-determination. A chance encounter with members of the Howard University branch of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during Carmichael’s senior year of high school prompted the young man to reject scholarships from several white universities in order to study at Howard. There, Carmichael quickly became involved in the Civil Rights movement. By the end of his freshman year in 1961, he joined the Freedom Riders on their racially integrated bus trips, which were organized in defiance of laws banning such interstate travel. Carmichael, like many of the Freedom Riders, endured bitter racism, mob violence, and arrest for his participation.

After graduating from Howard in 1964, Carmichael helped educate and register disenfranchised African Americans as part of the SNCC’s Freedom Summer, and in 1966, he was chosen as chairman of the organization. However, by this time Carmichael had begun to question the effectiveness of the nonviolent strategies long advocated by the mainstream Civil Rights movement. After being jailed for the twenty-seventh time at a rally in support of James Meredith (who had been wounded by a sniper on his “Walk Against Fear” from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi), Carmichael made a decisive turn in his politics, declaiming after his release, “We been saying ‘Freedom’ for six years . . . . What we are going to start saying now is ‘Black Power!’”

During the next few years, Carmichael spoke frequently on college campuses across the country to audiences who embraced his more radical vision for achieving an end to white oppression of African American communities. After severing ties with the SNCC, which maintained its allegiance to ideas of nonviolence and integration, Carmichael became honorary prime minister of the Black Panthers. But he soon found himself at odds with the Panthers over the role of white radicals in the movement. In 1969, he moved to Guinea, where he renamed himself Kwame Ture in honor of two of his heroes: Kwame Nkrumah, who had helped lead Ghana to independence, and Ahmed Sékou Touré, the first president of an independent Guinea. Until his death in 1998, Ture continued to advocate for revolutionary liberation. Top