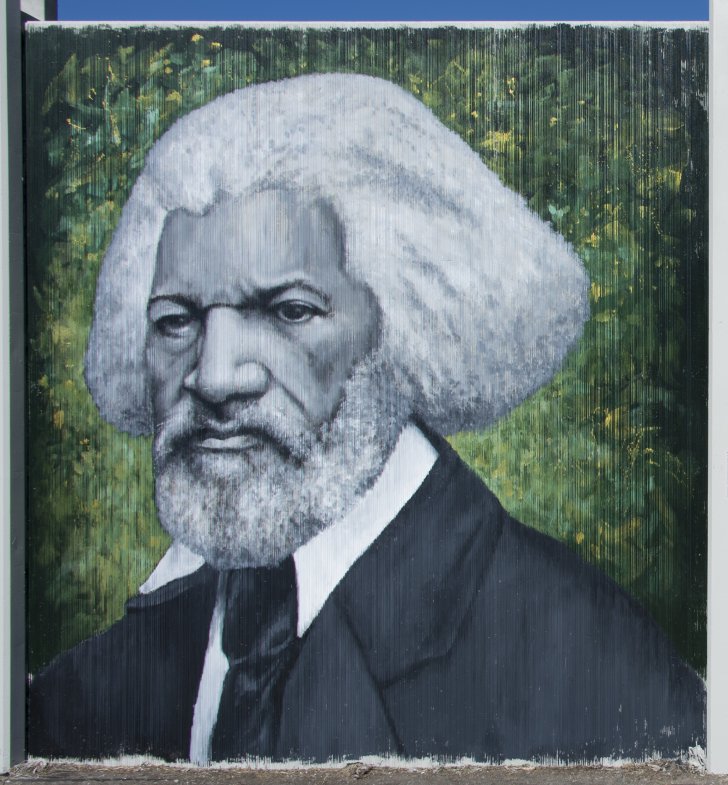

Frederick Douglass

Julia Bottoms’s portrait of Frederick Douglass for The Freedom Wall, 2017. Photograph by Tom Loonan.

A former slave, Frederick Douglass was one of the most influential voices in the abolitionist movement prior to the Civil War and in the work to ensure the full recognition of the civil rights of African Americans after the war’s end. After escaping in 1838, Douglass eventually made his way to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he quickly came to the attention of the local abolitionist community as a powerful orator. In 1841, he was hired by the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society as a traveling public speaker, and in 1845, he published his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself. While the immediate success of the book brought needed attention to the horrors of slavery, the publicity also inadvertently put Douglass at risk of being captured and re-enslaved. He would spend the next two years in Britain, continuing to speak out against slavery and returning to the United States only after a group of British friends purchased his freedom.

On his return, Douglass moved to Rochester, New York, where he began publishing the North Star, a newspaper dedicated to ending slavery and promoting civil rights for African Americans, and he became active in helping escaped slaves make their way to Canada. During this time, Douglass continued his public speaking, and in an 1857 speech, he delivered one of his most powerful calls on the potential of the oppressed to resist oppression: “Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them, and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.”

Douglass was an early supporter of Abraham Lincoln in his bid for the presidency, and following the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, he became an active recruiter of African Americans for the Union army. Throughout the war and in the years following, Douglass leveraged his influence in the government to fight for new legislation and enforcement of existing laws protecting the civil rights of African Americans. Until his death in 1895, he was a committed advocate for the right of African Americans to vote—which was finally codified in the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870—and against the emergence of segregation laws that threatened this and other rights in the American South in the wake of Reconstruction’s failures.