Since 2019, anti-Asian hate crimes in the United States have risen to an unprecedented level. In 2021, Mizin Shin, an artist, educator, and cofounder of Buffalo’s fine art print studio Mirabo Press, began Use Your Voice #StopAsianHate, a campaign to encourage everyone to speak out against racially motivated prejudice and violence. We spoke to Shin about the campaign.

Please note: this conversation took place prior to the racist shooting in Buffalo. In the same weekend, two other racist attacks were carried out: one in Dallas, Texas, injuring three women of Korean descent and another in Laguna Woods, California, motivated by anti-Taiwanese sentiment that killed one person and injured five others.

How did #StopAsianHate begin and what made you want to do it?

After the Atlanta spa shooting in March 2021, I kept hearing about events and news articles about the big increase in the rate of hate crimes against Asians in the US. It made me feel anxious and unsafe, and disappointed by what felt like a not-so-serious public response. At a certain point, I had to stop watching the news because I was getting really depressed and unproductive. At the beginning, I started making the prints more for myself and to encourage myself to speak out about how I felt on social media.

Actually, the whole idea of raising money with my prints started when Gail Nicholson, former executive director of Western New York Book Arts Center, saw my post about the first embossed prints I made, and she texted me to ask if she could buy the print for her daughter. I immediately changed the direction of these prints to pursue a larger scale campaign project. If there are people out there who want to buy these prints to show and spread support for their family and friends, I could help express that support and reach more people. So I made more prints (a lot more prints) to offer as appreciation for people contributing to all kinds of organizations supporting many different AAPI communities in a variety of ways.

The message is being translated into a variety of languages to engage diverse linguistic communities. There are two versions of the prints being made: (1) blind embossed prints and (2) screenprints—these are being traded in exchange for donations to organizations supporting Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities.

What problem or problems do you see that you want to address through the project?

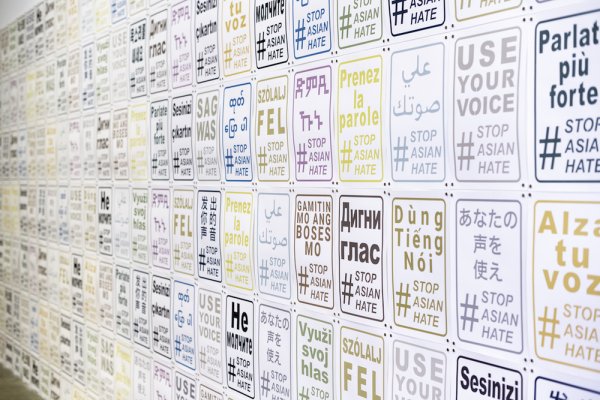

The catalyst was the big increase in the rate of crimes targeting Asians—but the truth is it has always been going on. It did not just happen suddenly. It started happening (or perhaps being reported) more and more in public view, but still there is a lack of awareness regarding how painful these issues are to the affected communities. So, I wanted to screenprint these signs and distribute them to other places where there are large Asian communities like Los Angeles, New York City, Vancouver, Toronto, etc. so people there could feel supported and welcomed in their communities. I was inspired by the Black Lives Matter signs displayed in windows and on lawns, and how that signals to individuals they are welcome in these spaces. The decision to use multiple languages was an invitation for other members of our local communities to pay attention to these issues as well as address the idea that just because you are not Asian, does not mean you cannot talk about these human rights issues.

Some people believe you need to be a direct victim to speak out about hate crimes and racism, but your awareness and using your voice to speak out on these topics helps others feel safer in our neighborhoods. I am doing better these days, but for a while, I was afraid of going outside by myself without my husband. I was afraid that no one would be willing to help me if I were threatened or attacked. But this one sign could make someone feel safer. As an Asian person, when I go to a new neighborhood, if I see a sign sharing public support for Asians or other minority communities, I do feel a bit safer.

Can you describe the project so far? There was an exhibition at Western New York Book Arts Center, right?

The screenprints were used for wider distribution. It is a quicker process than the blind embossed prints so I was able to produce a lot of signs in little time. When I decided to have an exhibition, I wanted to display all the signs in different languages together to create an environment that highlights unity in celebration of our diversity. Since I started showing the work in galleries, I have also been selling the screenprints at lower prices than the embossed prints for fundraising. The money from those prints is donated to a variety of organizations supporting AAPI communities in many locations.

It was not an easy decision having exhibitions with this campaign, personally. All my projects include my personal philosophy and beliefs, but this project was something I was doing as part of the Asian community, and I did not want to be in a position of benefiting from tragedy as a visual artist through opportunities for exhibition. Ultimately, I do have the privilege of getting attention through my artwork and so I felt the larger message is significant enough that I have a responsibility to exhibit the work.

I have also been doing workshops alongside the exhibitions. Participants come to the gallery and look at the installation and prints in the gallery as well as make prints with me. They can experience the printing process, and then share their prints, t-shirts, or tote bags with their family, friends, and neighbors, amplifying voices in their own communities.

Why address these problems through printmaking? Does printmaking lend itself to causes/activism in a way that other artforms do not?

The social power of print is deep-rooted in the history of printmaking, and that is something I often center in class by working with my students to produce work with the intention of interacting with a larger community outside our regular gallery-goers.

One of the primary characteristics of printmaking is multiplicity. There is a democratic aspect to producing consistent visual information for large-scale consumption—the same work quality and art experience is available to all, not just the highest bidder. An underlying aim of this project is not only to invite visitors to engage in the amplification of often unheard voices, both through local community displays and mass distribution, but also to highlight the social power of prints and printmaking.

But ultimately, I just find the process of printmaking enjoyable and somewhat soothing; the labor keeps my mind occupied.

What went into the look of the prints?

In terms of design, the prints are modeled after street signs. They signal public safety; they are informative, but also common enough to feel friendly, identifiable, and not off-putting to viewers. With the blind embossed prints, you cannot really read the text until paying closer attention and moving around to see the light and shadows on the paper. It provokes a kind of motion that could be applied to looking at societal issues of discrimination and bias. Getting a good view of the whole picture might require adjusting our perspective and moving around a little bit, away from our own bubble, to see things from another angle. Similarly, the screenprints use a metallic ink that has a subtle shimmer from different points in the room.

How have you felt personally about anti-Asian hate? Has it changed as a result of initiating this project?

Something that I have stopped saying is that I have been “lucky” that I have not had to personally deal with too much anti-Asian hate directed specifically at me in my communities. I do not know why I had perceived that it should be a matter of luck or some fortunate thing. It should just not happen. I should not have to say I feel lucky to not experience racial prejudice today. That should be expected.

When people come to the exhibition and share their personal experiences and find some sense of communal healing, that really means a lot. Or when people come and tell me they had not known much about this topic before seeing the work, that confirms the continued need to raise awareness. We need to normalize kindness in ourselves, in our families, friendships, workplaces, and larger social circles. There are many spaces in which some of us may be unsure that we will be welcomed. We can signal, sometimes by displaying literal signage, that we want all members of our communities to feel safe and appreciated.

About Mizin Shin

Born and raised in South Korea, Mizin Shin graduated from Hong-ik University with a BFA in Printmaking and received her MFA from SUNY at Buffalo. Leading numerous printmaking workshops with numerous art organizations, Shin focuses on both traditional and contemporary printmaking practices to promote a multidisciplinary approach to the medium.

Shin's work has been shown nationally and internationally at institutions across the United States, the UK, Spain, and South Korea. She is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of Art & Art History at the University of Rochester.

Shin has recently led a workshop with Korean American Artist Collective as part of their DIY Virtual Art Workshop series. Sign up for the KAA’s final workshop on pop-up books.

Shin is also a cofounder of Mirabo Press, a fine art printmaking studio in Buffalo. See more of her work and learn more about the campaign at Shin's website.