On the occasion of Women’s History Month, and in conjunction with the National Museum of Women in the Arts’ fourth annual #5WomenArtists campaign, we're highlighting five women artists with works in our collection each Wednesday this month. This week we focus on artists whose works are included in our current exhibition We the People: New Art from the Collection.

Although Huma Bhabha originally trained in printmaking and painting, she is best known for her figurative sculptures in cork, clay, Styrofoam, wire mesh, and other materials. To make the 16 prints in Reconstructions, 2017, she “took lots of black-and-white photographs, mostly of stalled construction sites and desert landscapes near the sea” during a trip back to her native Pakistan. According to the artist, she then “made enlargements and began drawing on them with pen or brush and India ink. I started out with feet, which in the context of the photographs looked enormous—as though they belonged to giants or were close-ups of monumental sculpture. But I also made drawings that showed figures in architectural settings or reclining in barren landscapes, as well as drawings that were more abstract.”

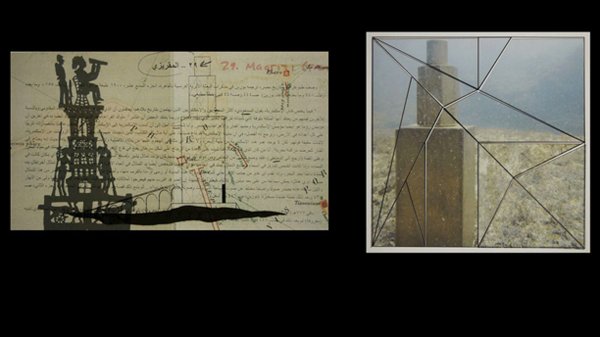

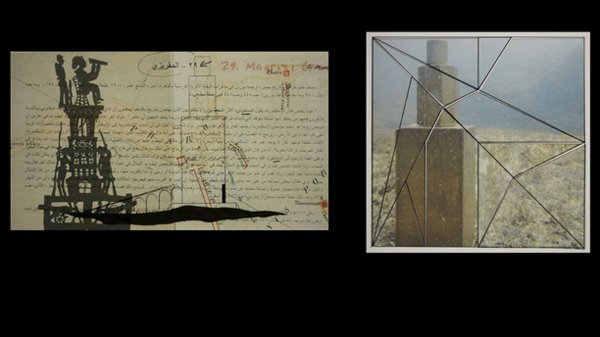

Ellie Ga bases her narrative projects on historical and geographical explorations that span a wide range of media, including performance, photography, video, sculpture, and installations. She uses these tools to probe the distinctions between documentary and fiction, personal and civic histories, textual and visual information, and photography and film. Measuring the Circle, 2013–14, belongs to series of works that Ga based on the destroyed Pharos Lighthouse of Alexandria, Egypt. On the left side of the video, she interweaves materials relating to the lighthouse with footage documenting her research process. On the right side, she plays an ancient Greek geometry game with cut-outs of these images, creating a visual metaphor for her attempt to fit together pieces of the lighthouse’s story.

Park McArthur translates her experience as a wheelchair user into quiet but politically charged reflections on how structures of dependency and autonomy dictate the ways in which bodies move—or are stymied—in social spaces. McArthur is particularly interested in how institutional or municipal signage operates to instruct, or impede, access. In Softly, effectively, 2017, she arranged a pair of signs to mimic the back-to-back configurations that hang above and across multidirectional highways. By choosing not to add any paint or symbols, McArthur created a marker that functions as a silent monument to no place in particular and yet evokes a sense of mystery.

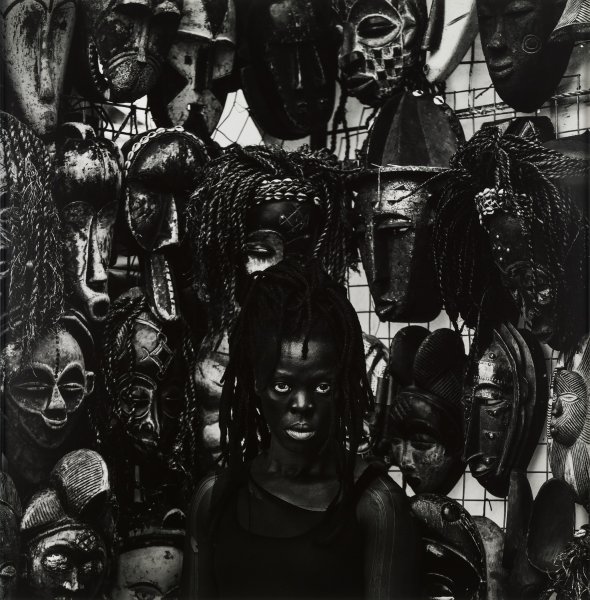

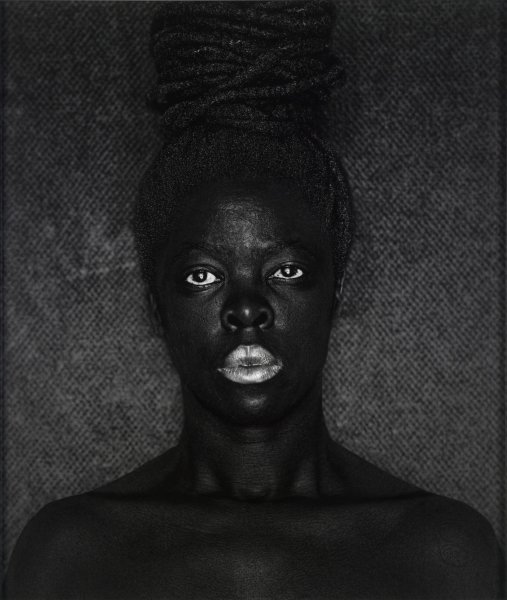

Zanele Muholi uses light and contrast to exaggerate the darkness of black skin in the three self-portraits on view in We the People: Fezekile IV, Cincinnati, Zonk’zizwe; Green Market Square, Cape Town; and Misiwe III, Bijlmer, Amsterdam. Muholi’s bearing suggests an unapologetic pride in black identity. “Just like our ancestors,” the artist has said, “we live as black people 365 days a year, and we should speak without fear.” At the same time as they celebrate the beauty of blackness, these photographs also allude to problematic representations of people of color by white artists throughout the history of art.

Jaune Quick-To-See Smith's Homeland, 2017, belongs to a body of paintings that she has created since the 1990s in which she explores the intersection of identity and place through the schematic map of the United States. In Homeland, multicolored rays emanate from the Flathead Reservation in Montana where Smith grew up. In redefining the contours of the country outward from this spot, Smith counters the presumption that a nation’s “heart” should be centered in its political, financial, or cultural capitals. In doing so, she raises questions about where we find our own centers and how we form our identities in relation to our concept of home.