My obsession with the work of Clyfford Still began in the summer of 1999 when I took a temporary job as a security guard at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery. Monet at Giverny: Masterpieces from the Musée Marmottan was a wildly popular exhibition and the museum needed more security.

My job responsibilities that summer mainly entailed crowd control and making sure people didn’t touch the paintings. It wasn’t until my second or third day that I was assigned a spot upstairs and first saw the room dedicated to Still. I was transfixed, and the rest of that summer I attempted to spend as much time in that room as I could (while still doing my job, of course).

The City of Denver was chosen by the Still family over 20 other bidding cities and the Clyfford Still Museum was founded in 2005. It would be four more years before they broke ground on the building and it would open two years after that. Thanks to the Internet I followed all of this while living in Chicago, where I had moved in 2001 after graduating from the University at Buffalo. Thankfully, the Art Institute of Chicago has two Clyfford Still paintings that I would visit often while waiting on more news from Denver. This year, I was finally able to visit this museum.

Walking up to the building it was a bit hard to believe. Downtown Denver at 10:30 am was eerily quiet, as it was July 4th and most offices and businesses were closed. We paid, and readied ourselves while we waited for the introduction video to start. Watching the five-minute video giving a brief background on Still and the museum, I almost started crying. The years of anticipation had definitely caught up with me.

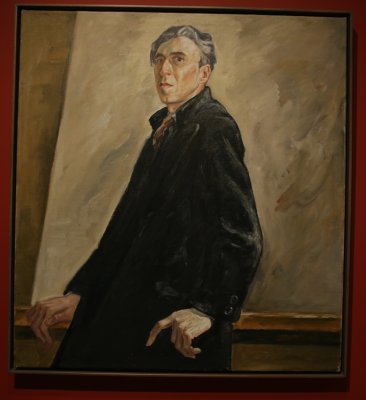

Walking up the stairs to the main gallery you are greeted by a self-portrait of Still followed by some early landscape work. What is interesting about these works is, while they are clearly before his shift to complete Abstract Expressionism, they already show the ideas he would develop as part of a more definite and permanent technique. The museum is mostly set up chronologically such that you walk through Still’s painting life from earliest to most recent. This was punctuated by a few rooms that, at the time of our visit, were dedicated to showing the process of restoration. According to the information posted by the museum, only about 10% of the collection needed restoring, but the work involved varied. Still stored many of his paintings rolled up in tubes and, in some cases, masking tape had cemented itself to the paintings. Other paintings had shown their years with faded colors or other physical damage. These galleries showed the viewer the process an art restorer would go through—a complex mix of physical chemistry and interpretation of the original artist notes—to determine the best plan of action. This was fascinating, as it gave an in-depth look into both Still’s creative process and this interesting job.

The last few rooms were dedicated to Still’s later work. The canvases were even larger, with a pronounced use of open space, allowing your eye to take them in and drawing a certain sense of perspective with their intensity. Where earlier painting had layers of dark blue and black with yellow and red streaked through, these later paintings showed more bare canvas or just simple white tones. Bursts of reds, like the last embers of a fire, hovered on these expansive canvases. I spent my last hour or so sitting on the bench in the relative silence of the gallery, taking in each of these last six paintings. I thought about nature and sound, each of these paintings reverberating a kind of cosmic tone the longer I looked at it. It makes a certain sense that Clyfford Still painted with the idea that his paintings would be considered carefully and that deep emotion and thought would spring forth when they were beheld, especially in his ideal setting. These are not mere works one rushes by or takes for granted. These are masterpieces deserving of consideration.

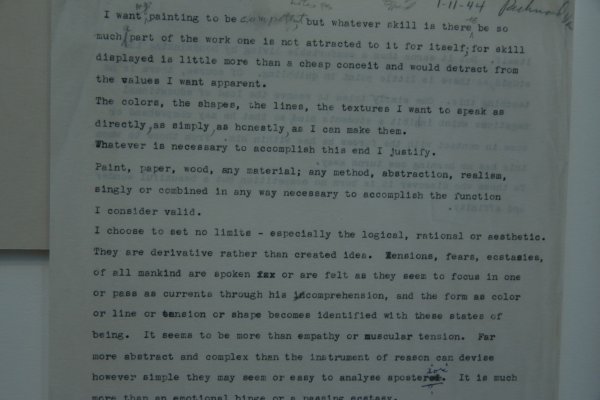

I finished up the visit with a quick trip back downstairs to look over the collected ephemera. On shelves were Still’s record and book collection, pictures of him with his kids and a fancy car (I guess he was quite the car aficionado). While all these artifacts gave me another side of Still to consider, I continue to be in awe of the mystery. I read over the letter Still sent to his art dealer in 1951 informing him that he would no longer be selling any of Still’s work. I left the museum in awe and inspired by Still’s courage and ultimate confidence in his own work. I also read over the response he gave to a journalist when he didn’t like what was written about him in an art review. Still had a certain sort of sensitivity and protectiveness of his work, and his fight for his vision has led to a museum committed to restoring and displaying his art exactly how he may have wished, and has given grateful fans of his art something very special in return.