A New Installation by James Turrell

Monday, January 1, 2007–Monday, December 31, 2007

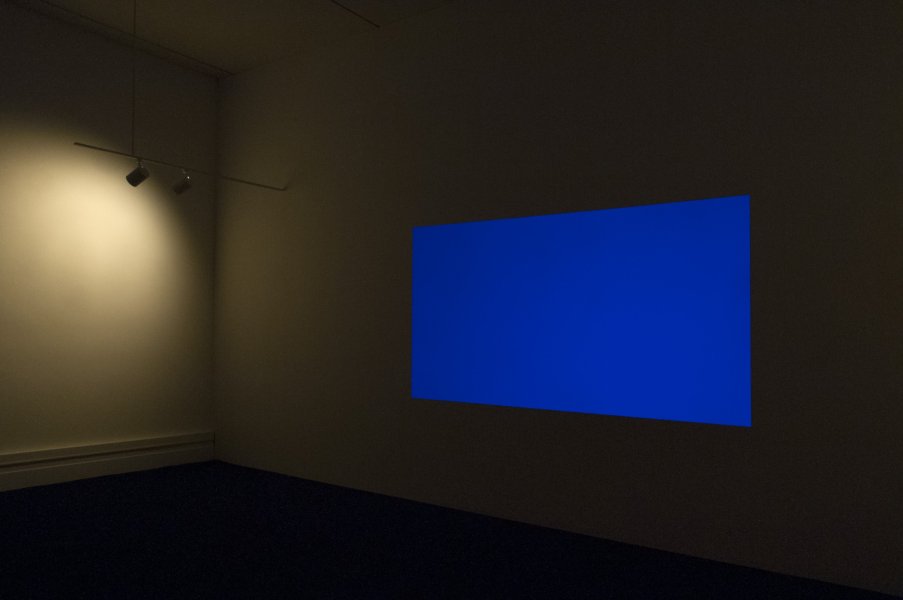

James Turrell (American, born 1943). Gap from the series “Tiny Town,” 2001. Light installation, dimensions variable. Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; General Purchase Funds, 2005 (2005:44). Photograph by Tom Loonan. © James Turrell.

“My work is about your seeing. There is a rich tradition in painting of work about light, but it is not light—it is the record of seeing. My material is light, and it is responsive to your seeing.”

— James Turrell

James Turrell isolates a central component of everyday experience—light. His installations grow out of a radically simple goal—to let the viewer experience light as directly as possible. In indoor installations such as Gap from the series “Tiny Town,” 2001, he lets light take on its own otherworldly quality, creating a contemplative space where one experiences a single plane of illuminated color. As viewers are forced to pay close attention to their own perceptions, their sense of reality is challenged, and the resulting instability generates a daydream experience. Turrell says, “It’s this daydream space overlaid on the conscious awake reality that I like to work with. It takes on the lucidity of a dream.”

Turrell is indebted to many sources in his exploration of the dynamics of perception, the beauty of light, and the spiritual connotations and allusions light inspires. The son and grandson of Quakers, he attended services when Friends sat quietly together to wait for individual enlightenment, an experience his grandmother called “greeting the light.” An accomplished pilot and son of an aeronautical engineer, his work draws on his constant transversal and altered perception of the landscape by air. He majored jointly in mathematics and perceptual psychology, which emphasized optics and visual phenomena, and pursued both art history and studio art courses. His works pulsate spiritually with the force and complexity of ancient astronomical structures such as Newgrange, the 14th-century Italian frescos of Giotto, and Mark Rothko’s 1950s abstract paintings, which generate an inner light. Yet, Turrell’s environments offered a kind of total immersion associated more with being in the landscape than in a gallery.

Turrell appeared on the art scene in the mid-1960s as part of the California light and space movement—an offshoot of Minimalism that took the literal and experimental nature of this New York movement in a different direction by focusing on visual perception itself. Since 1974, Turrell has been working on his magnum opus, the Roden Crater. He is converting an extinct volcano north of Flagstaff, Arizona, into a viewing platform (or naked-eye observatory) by subtly altering the elliptical shape of the crater and creating viewing rooms, which open to the sky in unique ways, where one can better experience the light of the sun, moon, planets, and stars.

A work by Turrell takes time. Allow your eyes to adjust to the reduced light levels. Allow your mind to quiet so that it can focus on the experience in front of you. As with any experience of focused attention, whether it is enjoying a sunset or a favorite piece of music, a certain open contemplation is required. Allow the experience to fully unfold in front of you. Part of the magic in experiencing this artwork is the sense of acute perception that results.