By Gerald Oster

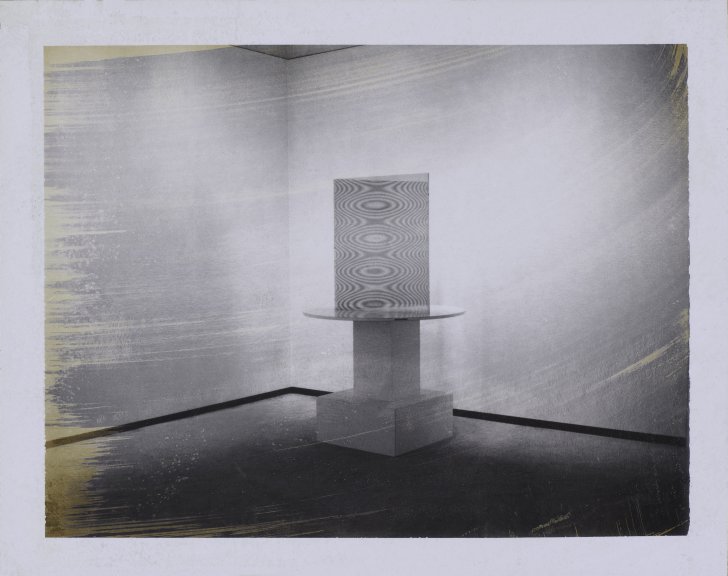

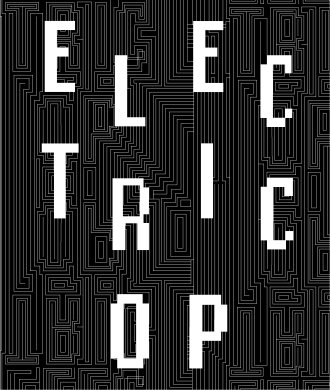

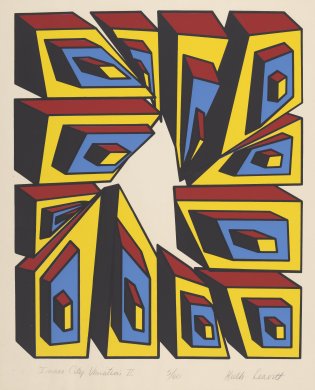

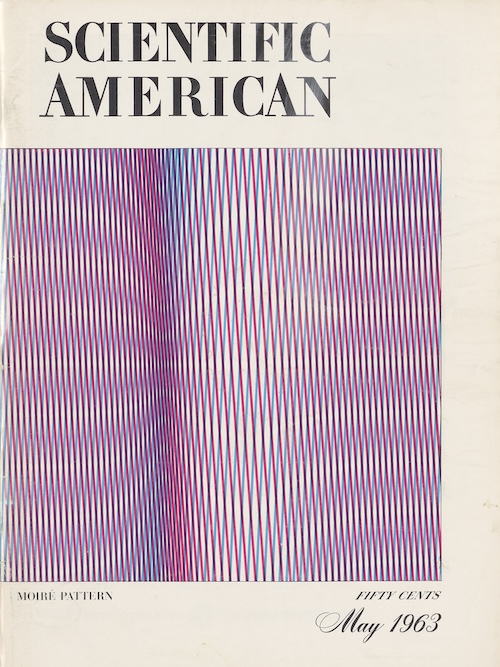

The following text is included in the catalogue for the special exhibition Electric Op, on view through January 26, 2025. Dr. Gerald Oster was a biophysicist whose interest in moiré effects led him to becoming one of the major practitioners and proponents of “Optical art.” His works were included in the major Op art surveys presented in the spring of 1965 by the Buffalo AKG Art Museum (then the Albright-Knox Art Gallery) and the Museum of Modern Art, New York; they even inspired a short 1967 film called Moirage by the avant-garde filmmaker and digital animation pioneer Stan VanDerBeek. Oster regularly exhibited at New York’s Howard Wise Gallery, which featured Op and kinetic artists and organized the first exhibitions of digital and video art in the United States: 1965’s Computer-Generated Pictures and 1969’s TV as a Creative Medium. Oster advocated for the bridging of the arts and sciences and his articles appeared in a variety of publications, from Art Voices to Applied Optics (excerpted below). His designs also appeared on the covers of Vogue and Scientific American alike, turning moiré patterns into one of the most iconic elements of popular culture in the 1960s.

[…] Optical art is an unfortunate term since all visual art is optical.

Whether or not one is able to explain visual impressions in terms of the science of optics, it is usually agreed that all visual phenomena up to the point where they register on the retina fall properly in the domain of optics. Hence at this level, art is a branch of applied optics. The integration of the visual information by, at its lowest level, the nervous system immediately associated with the retina and by the brain (more specifically the visual cortex) properly falls in the domains of nerve physiology and of the psychology of perception. The view which the eye usually sees is so complex that most physicists would be reluctant to engage in an analytical study of the optics of the problem. Even in the relatively simple case of diffraction, the conditions of Fraunhofer are much preferred over the Fresnel conditions for purposes of mathematical simplicity. It is from the complex picture that we abstract the relatively simple pieces of information for our survival and for our understanding of the world. Science now has the machinery, namely, the digital computer, for the solution of complicated optical problems. Furthermore, analog aids, such as the moiré technique, can help the optical scientist arrive almost intuitively at the answer to some involved problems in optics such as those encountered in the visual scene.

An understanding of the real world is as important to the artist as it is to the scientist. For artists, however, their world includes the totality of perception and the emotional response one derives from it. Nowhere does art and science seem to be on such common ground for discussion as it does in optical art. Whether or not optical art conforms to one’s tastes, it is worthy of consideration (or, better still, study) by scientists directly concerned with optics. Optical art is so intimately connected with visual information at its foundation that it is bound to be with us for a long time. Certainly optical art has much to teach the artists, and elements of it, at least, will be incorporated into much of the art of the future. Optical art is one manifestation of the cultural activities of our contemporary society; in particular, optical art makes us aware that man is an organism. Still further, it is executed with a precision characteristic of the technology of today. Regardless of its role in our culture, optical art can bring to the understanding and sympathetic viewer much the same joy and wonderment of the world that, say, an optical scientist felt as a student when he first appreciated the magnificence of Maxwell’s equations and their applicability to the whole of electromagnetic phenomena. […]

Artists have another source of inspiration for their work. [Bela] Julesz at the Bell Telephone Laboratories has shown that depth perception need not depend on the presence of a recognizable form. Thus, depth is perceived when one views stereoscopically two computer-produced random dot patterns one of which is a copy of the other but with a portion slightly displaced. By this means one can produce a variety of three-dimensionally appearing objects which need not occur in nature. In fact, by proper programming one should be able to produce with the digital computer, objects which lie beyond the imagination of even the most imaginative mathematicians such as [David] Hilbert. All this may have a terrifying aspect to most artists, but it is no worse than da Vinci’s admonition to sixteenth century artists when introducing his treatment of the geometry of perspective, “let no man who is not a mathematician read the elements of my work.” Computer technology has far to go to duplicate the spirit and excitement of art. When such a day is reached, however, it will require an artist to do the programming.

Excerpted from Gerald Oster, “Optical Art,” Applied Optics 4, no. 11 (November 1965): 1359–69 (excerpts on pp. 1359–60, 1368). Reprinted with permission from © The Optical Society of America.

To read more artist perspectives as well original critical essays, pick up the catalogue for Electric Op in the Buffalo AKG Art Museum Shop.