Tom Sachs describes himself as a bricoleur, a tinkerer, and someone who sees in the detritus of contemporary culture a fertile melting pot of ideas. Recycled tools, weapons, and electronics function as base material, along with corporate logos (Prada, Chanel, Sony, Tiffany), for provocative sculptures. The combination, or collision, of cultural commerce with themes of death and violence distinguishes the work—envision Duchamp’s arcane valise transformed into a compact survival kit stocked with guns, ammunition, bludgeons, gloves, and whatever else it takes to survive in today’s madcap world. Sachs is obsessed with the process of building. This constructive aspect of his studio practice—a meticulous attention to how something is made—is an essential part of the work’s character and significance.

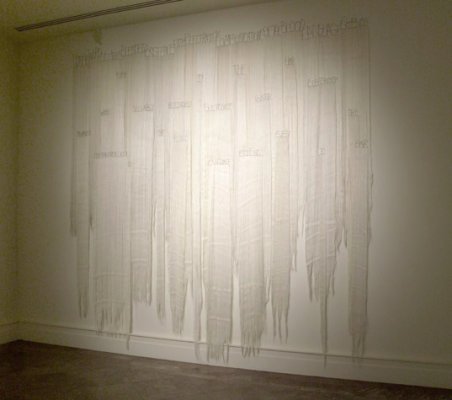

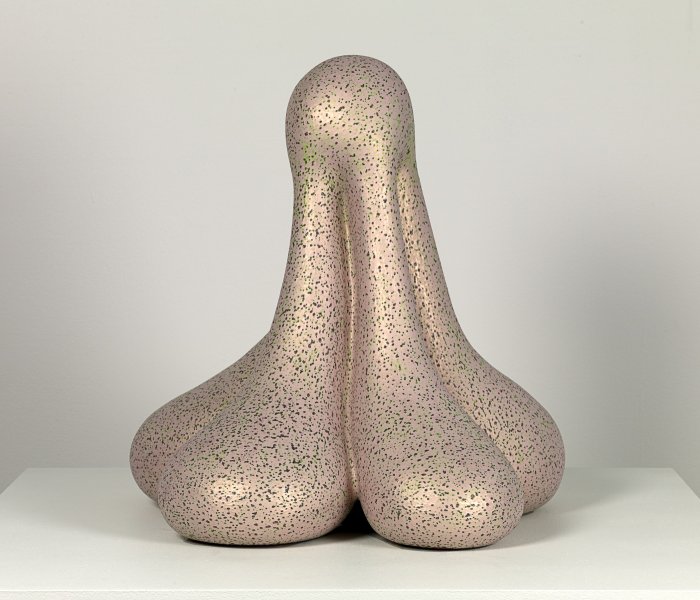

Language and narrative forge the base plane of Jeanne Silverthorne’s sculptural tableaux. For years the artist’s studio provided an arena for ideas that explore notions of creativity and authorship. Using common studio props such as light bulbs, plumbing fixtures, and electrical meters cast in rubber and combined with other casts of sweat glands and muscle bundles, she improvises within a particular space to create her own equivalent to a Rube Goldberg contraption. Silverthorne’s hybrid organisms—metaphors for biological circuitry, emotional states, doubt, and dysfunction—combine humor and skepticism in fascinating ways.

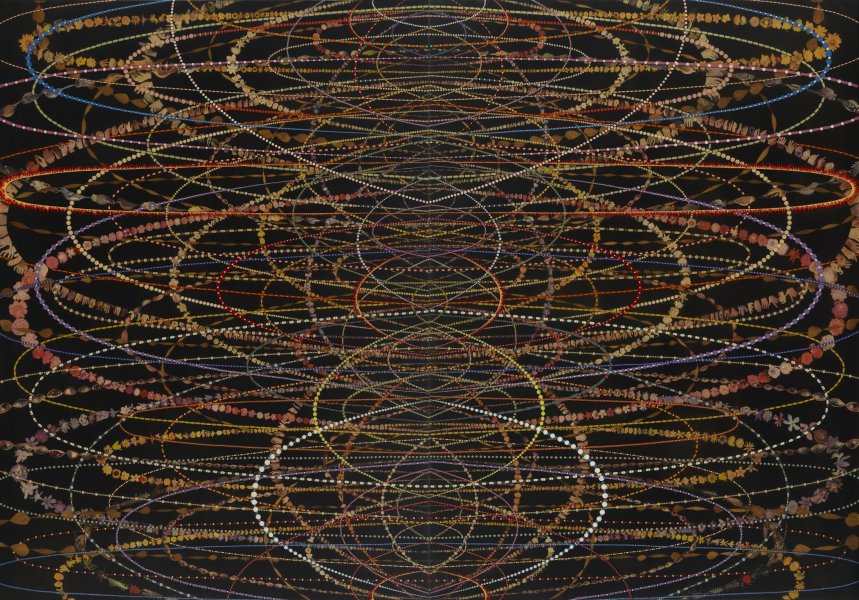

Fred Tomaselli combines painting, college, and other disparate materials (pharmaceutical drugs, cannabis leaves, reproductions of facial details such as eyes, hands, and lips clipped from fashion magazines) to create microcosms of electrifying intensity. His are complex and often disorienting worlds, which can take months to conceive. Some images—analogues for an uneasy equilibrium—pit order against chaos. Others, in their repetitive severity, resemble religious mandalas—unlikely vehicles for meditation. Still others appear entirely entropic. Tomaselli’s quirky constructions reflect his visionary and idiosyncratic worldview of insular universes where utopian pretensions, sometimes serious, sometimes tongue-in-cheek, in the end remain a relative proposition.

The museum hosted a Members’ Preview of the exhibition on October 3, 2003, with a panel discussion entitled “Comic Relief: Humor’s Edge in Contemporary Art.”

This exhibition was organized by Senior Curator Douglas Dreishpoon.