Cathleen Chaffee, Charles Balbach Chief Curator, as told to Matthew Connolly, Editor

Marisol: A Retrospective opened at the Buffalo AKG Art Museum in July. The exhibition was based in large part on Marisol's bequest to the museum of all the artworks in her possession at the time of her death. We asked Cathleen Chaffee, curator of the exhibition, to tell us how Marisol came to give the museum such a generous bequest.

Marisol made her first plans in writing in a will leaving everything to the Buffalo AKG Art Museum many years before she died. We learned that a major gift from the artist might be a possibility some time before she passed away, but we didn't have it confirmed until 2016. Marisol was a person who was almost uniquely comfortable with silence. Whereas many of us might fill the silence of a break in conversation, she felt really comfortable letting silence go on. She famously conducted at least one whole interview in which she didn't answer a single question. So we don't have a definitive answer from her about why she made the historic decision that she made to leave the entirety of her estate to what was at the time the Albright-Knox Art Gallery (now the Buffalo AKG Art Museum), but there are three threads, some of which she mentioned to friends.

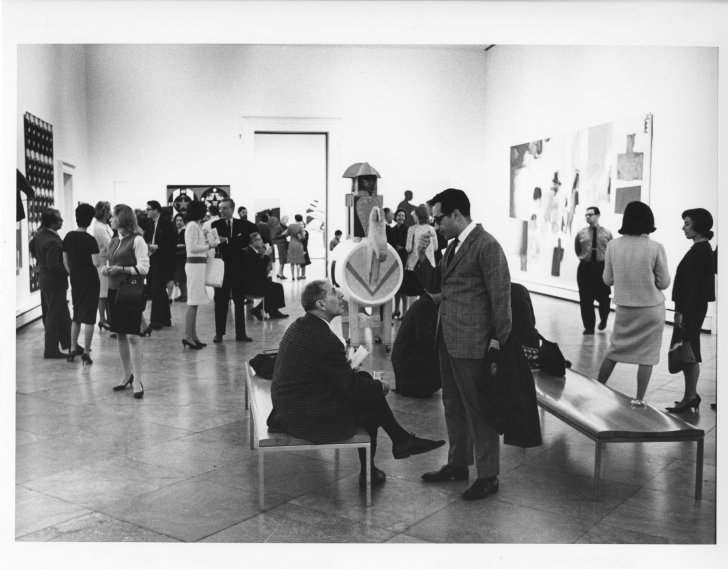

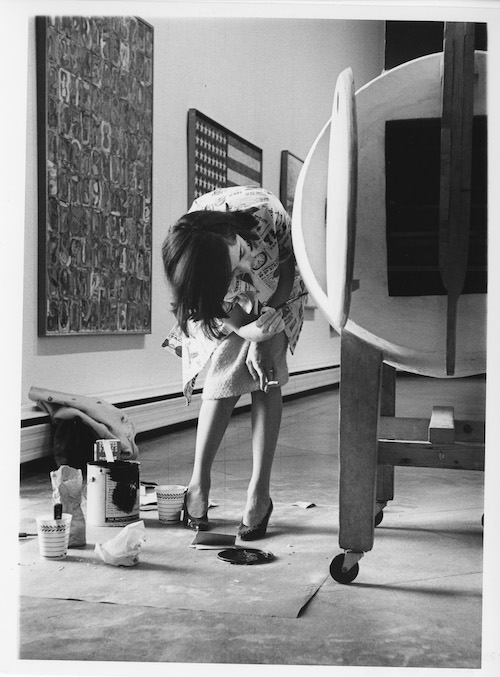

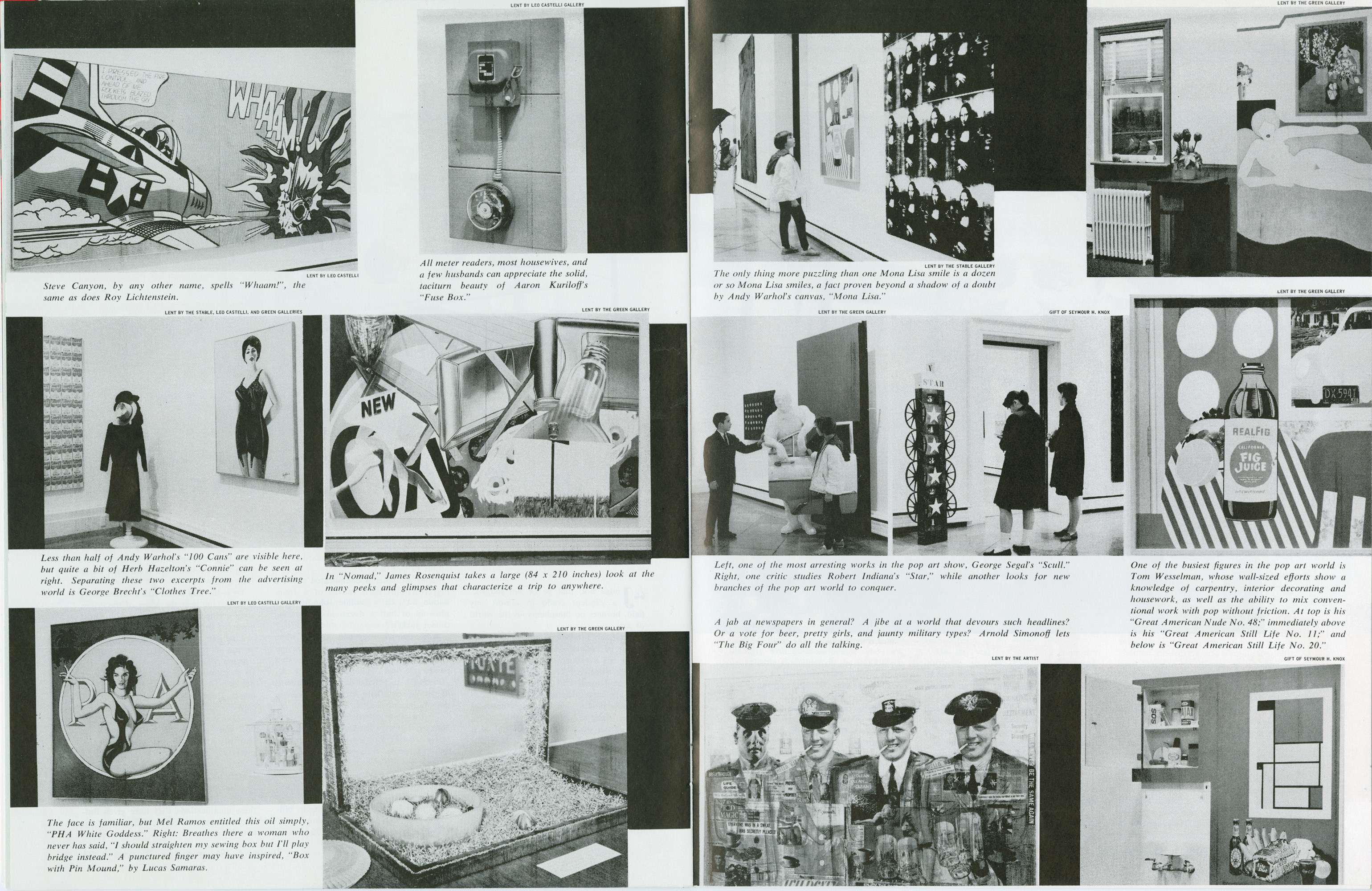

First: we were the first museum to buy her work with the purchase of the sculpture The Generals from her 1962 breakthrough solo exhibition at Eleanor Ward's Stable Gallery. This is a work purchased for the museum by Seymour H Knox, Jr., but acquired—as many works for the museum were acquired at that time—because of the shared enthusiasm between Mr. Knox and the museum's director Gordon M. Smith. Other museums acquired Marisol’s work around this period, including at least one that bought a work from the same show, but we paid our invoice first, and we also put the work on view almost immediately in the 1962 inaugural installation of the Knox Building and subsequently in one of the first exhibitions of Pop art to use the name in the United States, the show Mixed Media and Pop Art in 1963.

A sale of any kind was a great sign of validation to an artist, and to sell to a museum—especially for an artist who so valued museums as a place of learning as much as Marisol did—would have been a big deal. The Albright-Knox was widely known in the art world then as now for taking risks on young artists or new voices or artists that had not yet made their reputation. We were known for buying work “when the paint was still wet” in the 1950s and that reputation was still firmly in place in the ‘60s. More widely, in 1960s New York avant-garde artists had only recently gotten a taste of selling their work and feeling successful. It was only in recent memory that Marisol’s friend Willem de Kooning had opened his first bank account at the age of fifty. Presumably, he hadn’t had enough checks that needed cashing before then. Many Abstract Expressionist artists were showing in artist-run spaces, such as the Ninth Street Gallery in New York where few had expectation of selling. The New York gallery scene was also very small, and there were very few commercial outlets in which to sell your work. By the early years of the 1960s this was just beginning to change.

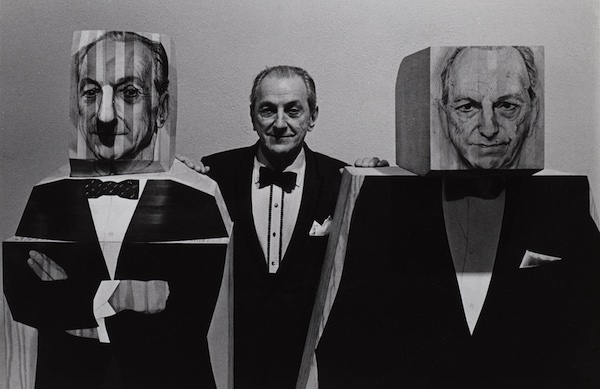

The second reason, perhaps just as important, is the fact that her longtime dealer, Sidney Janis, was from Buffalo. Janis was her gallerist from the mid-1960s and she stayed with the gallery for some years beyond his death in 1989. Janis was a one-time professional dancer on the vaudeville circuit and later a shirt manufacturer, who was always very dapper. She considered him, at least at one point, to be a kind of father figure.

An artist's relationship with their gallery can be a very close one, and Marisol and Janis’s relationship lasted from when she was in her mid-thirties and just really finding her way in the art world, through the heyday of her success in the 1960s, until a time when she was selling less and she was receiving a lot less critical attention. Invariably, Janis continued giving her solo shows and advocated on her behalf. Obviously, they also disagreed, but I think she felt very supported by him. His ties to this museum in Buffalo—we even did an exhibition of his collection—may well have played a role in her decision-making. We had a long relationship with him, and acquired many iconic collection works through him, including Arshile Gorky’s The Liver is the Cock’s Comb (1944), and Jackson Pollock’s Convergence (1952).

Marisol never married, never had children, and she had no heirs nor a gallery when she died. After Janis, her other relationships with galleries collapsed. And that comes to the third reason, the final reason that she chose to leave her estate to the museum, which is the fact that although she would eventually receive many accolades and even an honorary doctorate from the University at Buffalo in 1992, Marisol never went to college. She moved to New York in 1950 with the idea she was going to go to school, and in the end, took classes at various schools all over the city, but she would ultimately say that her university, her training as an artist, came from libraries and museums. She had great faith in the power of museums. So I think her decision to leave her estate to a museum comes from this formative, and ongoing experience of being nourished by these civic institutions throughout her career as an artist. Taken together with her ties to Buffalo through our early acquisitions and exhibitions of her work and through Sidney Janis, we may arrive at a better understanding of her decision to entrust Buffalo with such a momentous bequest.