My house has hundreds of rooms, and I have more friends than I can count.

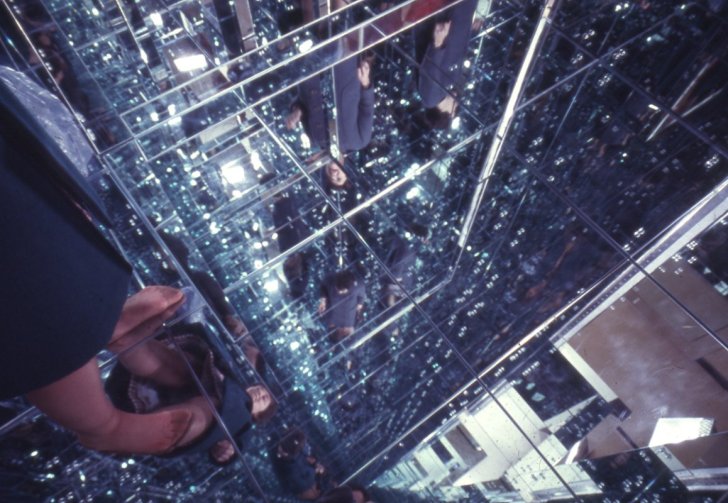

They move when I move, sleep when I sleep, and they are fed when I am fed. They look towards the crack in the wall of their room when it opens with a soft click and hiss of air, and like me, try to peer out at whatever is beyond, in the thin, black rectangle that appears there. If they can see more than me, see past the darkness when the plate of food is slid from the deep blackness, coming to a stop on the glass floor, they do not tell me. They cannot speak unless I am speaking to them, and then our voices overlap so I can never hear what they are trying to tell me.

We have always been in these rooms, stacked side-to-side and on-top-of-each-other for as long as I can remember. Our house must be very large to hold all of my friends, and their friends, and their friends.

“Do you have a window?” I asked once, knowing the friend to my left would repeat the question all the way down to the last person in the row of rooms. The last person in the row wasn’t my friend—I couldn’t see them and had never spoken to them, even if I squinted and strained my eyes to follow the row of friends until their bodies grew minuscule. I already had more friends than I could count; I would let the message be relayed through one of them.

“No,” came the response, relayed instantaneously through all of us at once. My friends looked at me, as I looked at them, as if waiting for a response, a reaction that they would no doubt share.

My friends and I were very similar.

The long, black rectangle of darkness appeared in the corner of the room as I was lying on my back on the cold glass floor. Above me, one of my closest friends did the same, although he lay on the ceiling, looking down at me. When I noticed this for the first time, I giggled. He thought it was funny, too, pointing one finger down towards his floor, my ceiling. We tried to touch each other’s fingers, but we were both too short, even when we jumped. “Your timing is really good,” we complimented each other, when we jumped at the same time without even planning it.

The rooms above and below this one were upside-down to me, and I was upside-down to them. “You’re standing the wrong way,” I told them, and they told me, as I crouched to peer at the rooms stretching down, and down, and down. I didn’t look at the friends below me very much—if I looked past the first one, my stomach began to flip nauseatingly. It seemed as if my room was very high up, and I didn’t like that. The friends above me were alright, though; their existence, stretching up, and up, and up towards the sky reassured me that I couldn't be that high up, after all.

Today, the darkness that protruded from the crack in my room slid me a plate of food and a small stack of paper, bound and folded so I could flip through it. These stacks of paper came with my food, sometimes, and I read the words in them aloud to all my friends, who repeated them aloud to their friends, so no one was ever left out.

We enjoyed the stories; we enjoyed hearing about people like us, houses like ours. When I fell asleep at night, pressed back-to-back against the neighbor that lived below me, I wondered in my dreams if the other houses looked like ours, if the people within them looked like us. The stories, written in perfect black ink on perfect white paper, never said.

I waited until the crack had disappeared again to approach my plate of food and my papers. Some time ago, one of my friends had tried to confront the long, dark split in the seam of his room. I had followed, only to see what he would find, but before either of us could get close, it had receded and disappeared from view quicker than it ever had before. We had both pawed at the wall of the room, but the friends in front of us were confused, and pressed their palms to ours as we searched for where the crack had gone, perhaps thinking that we were reaching for them instead. We couldn’t see past their bodies, and when we pressed against the wall, their fingers pressed back, making it so there was no hope of prying it away to reveal where the darkness went.

“Move,” I told them, as they asked me to move.

“Move, please,” I tried. They tried to be polite, too.

In the end, we gave up looking for where the darkness had gone. I sat on the ground with my back turned and refused to look at them for a long while, until I realized that they must have been looking for the crack in the wall, too, and it was neither of our faults. Then, we apologized to one another.

I sat on the ground in front of my food, pulling pieces of it off of the plate and guiding it to my mouth until it was gone. I left the stack of papers alone for the moment—once, ridiculously, my friends and I had all managed to accidentally spill food onto our papers. The black words had smeared into blobs we couldn’t read, and we had spent a long time discussing what we thought they would have said. In the end, we all decided to save reading until we had finished our food from then on.

Once the food was finished, I pushed the tray back towards where I thought the crack in the wall opened up. It was hard to tell where that was, sometimes. I loved all my friends, but we were so similar.

Sometimes it was hard to tell which one was which.

Standing, I retrieved the stack of papers and turned to the first page. It was heavier and thicker than the stacks of paper we usually had, and as I weighed the stack in my hands I saw that my friends were doing the same. On the first page, in perfect black words, I read aloud.

BREAK.

I looked at the friend beside me and felt the other friends staring at each other, too. The words looked the same as they always did, but none of the stories had ever contained one single word, alone in the center of the page.

“It feels important,” my friend said. I had always thought this friend beside me, the same one who had walked towards the darkness, was smarter and braver than me.

“You’re right,” the rest of us agreed. We flipped to the second page, and my mouth fell open. I stared down at the brilliant colors, too entranced to notice or care what my friends were doing.

I knew what the sun was, from some of the papers the darkness gave me. But this was something I had never seen before.

Behind the sun, fluffy-looking patterns of warm color spread in a gradient from dark to light, the color encircling the sun was almost the same as the white paper bordering it. Below the sun sat something that looked like the water given with my food, only more of it than I had ever seen before. It filled almost the entire bottom half of the paper. It couldn’t be water, though—through it, there was another sun, and another wavering pattern of color.

“Is the sun in a house like ours?” I felt my mouth move to mimic the question but knew that one of my friends had asked it. “It can’t be,” another answered. “Isn’t the sun too big? Isn’t it hot?”

The questions kept coming, one after another, enough to make my head spin. I squinted my eyes and studied the picture hard, the center of my forehead throbbing in dull pain as I concentrated as hard as I could. There had to be an explanation for this. For the sun, and the glass below the sun, and the rest of it. But by the time the dull pain in my head had become a sharp pain, I still had no answers to give my friends. I turned the paper upside-down, hoping in vain that examining the second sun would reveal something new.

Instead, as I did so, something heavy inside the stack of paper dislodged and fell.

The paper tumbled out of my hands as I knelt stretching out my arms in an attempt to grab the heavy object as it plummeted towards the room of the friend below me. “Watch out!”

My breath came strained and terrified as I envisioned the object punching through the floor and hitting my friend. It was heavy enough that, dropped from that height, I imagined it would break bone. I squeezed my eyes shut, not wanting to see what would happen.

It hit the floor of my room, and the floor exploded.

I felt the vibration of an impact, heard a noise I understood as one thing becoming many, smaller things, and the floor seemed to come apart under my feet. My stomach dropped to my toes as I realized, I was going to fall through.

My heart pounded in my ears as I waited for the speed of the fall and the sudden stop, waited to feel my friend’s body inevitably crush under my own. Time seemed to slow down, and I held my breath until my head began to spin. There was the falling feeling, but when my backside met the cold glass floor of my own room, it held.

I gasped for air, and the falling feeling slowly began to disappear. My heartbeat, pounding rapidly in my ears, faded into the background. The fresh food in my stomach churned dangerously, but calmed somewhat as my gaze rested on the stack of papers, lying wrinkled on the ground. Grabbing for it with a shaky hand, I propped it open on my thighs, flipping past BREAK, flipping past the page with the two suns. The rest of the paper was sealed together, and a hole had been cut in the center of the stack, where the heavy object must have been sitting.

“Who would do this?” I asked, my voice trembling. The question was echoed by my friends, the fear and anxiety palpable through the glass, pressing in on every side of me. For the first time, I felt like perhaps my room was too small–although my house was vast, I was certain I could barely breathe.

Setting the stack of paper down beside me and planting my palms on the floor, I rested my weight on my hands. There was something sharp underneath one of them, and I hissed in pain as I felt my skin give way, parting around the sharp thing. I looked down, shoulders twitching in unpleasant surprise.

Beside my left hand, the greyish object sat in its crater of destruction, looking cold and sinister. It had no sharp edges, smooth like an egg, only flatter. Near it, bright red blood leached out from underneath my palm, slipping into the cracks between the glass. I imagined what it must be like, to live in the room beneath me. What would my friend be thinking, I thought, when he noticed the red droplets welling up from the floor? Was he sitting like I was? Would the blood press against his own palm?

Leaning over the object, I stared down, searching for my friend’s face, no doubt every bit as worried as my own.

Instead, a multitude of eyes met mine.

A noise of surprise fell from my lips as my gaze moved across the splinters of broken glass, lingering on each as if the sharp edges were snagging it. In every splinter, I found another piece of my friend. Fractured eyes, a warped mouth, a crooked nose, the angles slightly different in every piece of glass.

“Oh.”

My voice found itself in a horrified whisper. All at once, recognition of my surroundings rushed back to me, and my hands flew to my face, pressing the soft flesh and reassuring myself that I hadn’t befallen the same fate as my dear friend. Through the shattered floor, my friend felt his own face, smearing blood across his forehead and down his cheeks. There was blood on my skin, but I knew it was only from my hand.

“He needs help,” I said weakly, looking around. “Can…can one of you get to him?” My eyes rested upon my closest friend, one of the ones living beside me. To my horror, he sat upon the floor as well. His face was a pale mask of fear, smeared like mine with red blood turning cool as it dried. A long crack ran along the glass beneath him, but I could not see any strange object embedded in his floor.

“I’m sorry I cracked your floor, too,” I told him, and his eyes looked suddenly glassy, like he might cry. If he cried, I would. “I’m sorry, but someone needs to help him.” I pointed to my floor, and my friend pointed to his. “No, this friend,” I corrected, pointing again. “He needs help, he’s–” My voice went rough. “He’s broken.”

My friend fixed me with a blank, glassy stare as I waited for his response. Silence closed in upon me from every side, but the silence from below me somehow felt the loudest.

“I’ll do it myself, then!”

My voice alone was the one to break the quiet, and I turned back towards the object in the floor, towards the pieces of my bloodied friend, and began to sweep the glass away from the crater the object had made. If no one else would try to get to him, I would. I had never known my friends to be so selfish.

The glass pricked my fingers as I began to carefully clear it away, fat drops of blood splattering onto it. Once the red coated my hands, I could no longer tell whether it came from my body, or the body of my friend as I moved and shifted the glass that had broken him. I pressed my wet palm to the round, solid object, hand curling around it almost pleasantly, and lifted it with some difficulty.

Underneath, standing out amidst pieces of glass I had yet to clear, was a floor I did not recognize. It was cold, and gritty, and a darker grey than the object in my hand.

I could not see my friend through it. I couldn’t see anything through it.

Carefully, I placed the object a short distance away, turning back quickly to continue examining this new material. My room was made of glass, of that I was certain. But then, what was this new floor beneath my own? And, why was it obscuring my view into my friend’s room? Slowly, I stood, sidestepping the smears of blood my hands had left on the ground.

Below me, the soles of our feet aligning perfectly, was my friend, covered in red, but whole again.

The relief that should have been a cool balm through my body ran slowly, tempered into sluggishness by confusion. I stepped towards the grey hole in the floor and peered down at it; my friend did the same, except when he did so his shoulders and neck disappeared from sight, broken off in jagged pieces where the glass stopped and the grey floor began. I looked up; I could see a grey hole in the floor of the friend above me, too. Like the hole here in my room, I couldn’t see past it.

Falling to my knees, I pushed the pile of glass shards away, no longer worried for my friend’s safety. They went skittering across the floor with a musical sound that raised the hairs on the back of my neck.

“Do any of you know what this is?” I leaned down lower, and lower, and lower, until my cheek pressed to the cold grey floor, my face sitting carefully centered in the ring of pointed shards. I squinted, reached forward, and then dislodged a damaged piece of glass from its place in my floor. It pulled up from the grey material without much force, leaving me holding a small, impossibly thin sliver between my stinging fingertips. Glass this thin would never have held me, held all of us, walking and sitting and eating upon it for as long as I could remember.

In a moment of realization so stark that it nearly felt violent, another phenomenon made itself apparent to me.

I should have been able to see through to the other side of the glass. I should have been able to see my fingertips on the other side. Instead, as I gazed into the glass, I could only see my friend’s thumb pressed against mine, as if he was holding the glass from the other side.

I turned the glass over, fear climbing its way up my throat again.

The other side of the glass was a thick, blackish color. When I held it turned-over, my thumb alone pressed to the black.

My friend was nowhere to be found.

A wave of dizziness hit me, and I was glad my face was already resting on the floor.

“I don’t understand,” I whispered, my eyes glued to the piece of glass flooring now cradled in my palm like something precious. The rooms are made of glass, and glass is clear. I can see my friends through the glass, and they can see me. My house has hundreds of rooms, and they are all made of glass.

I cannot explain the room of the friend below me.

About the Author

Forest "Hem" Lovullo is a 23-year-old writer that was born and raised here in Buffalo, New York. His work has been featured in several local publications, but he has found a home for his short stories in the local The Bughouse Review zine. He spends much of his time writing, reading, volunteering, and performing in a chamber ensemble, and has recently been appointed as Assistant Publisher of Blind Printing Company, from which The Bughouse Review is published. He finds inspiration for his works in a variety of places, but most often in the city around him.

The first part of "Tenet," published above, originally debuted in The Bughouse Review, a monthly zine produced by The Bughouse Collective founded in 2023 and made up of a diverse group of artists from Western New York (Buffalo and Fredonia, mostly) who create art in various media and genres. To read The Bughouse Review, as well as "Tenet" in its entirety visit their website.